UW snake specimens show deadly fungus has been around for decades

In 2008, scientists discovered a fungus that was killing endangered snakes in Illinois, but preserved snakes in the University of Wisconsin Zoological Museum show that the fungus was already widespread in the United States more than 75 years ago.

Jeff Lorch, a microbiologist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, looked for the fungus, Ophidiomyces ophidiicola, on museum specimens collected decades before the fungus was isolated from Eastern massasauga rattlesnakes being studied for (eventually successful) inclusion as a protected species.

“What we were worried about around 2008 was whether this fungus was just introduced from somewhere else in the world,” says Lorch. “Those are the pathogens that concern you most from a wildlife disease management perspective, because a native species may have no protection against something that comes from far away, that it’s never seen before.”

Lorch examined more than 500 snakes in jars, preserved specimens at UW–Madison’s Zoological Museum and the former Morehead State University Museum Collection, looking for telltale lesions on the snakes’ skin. About 9 percent of them showed signs of infection by the potentially deadly fungus.

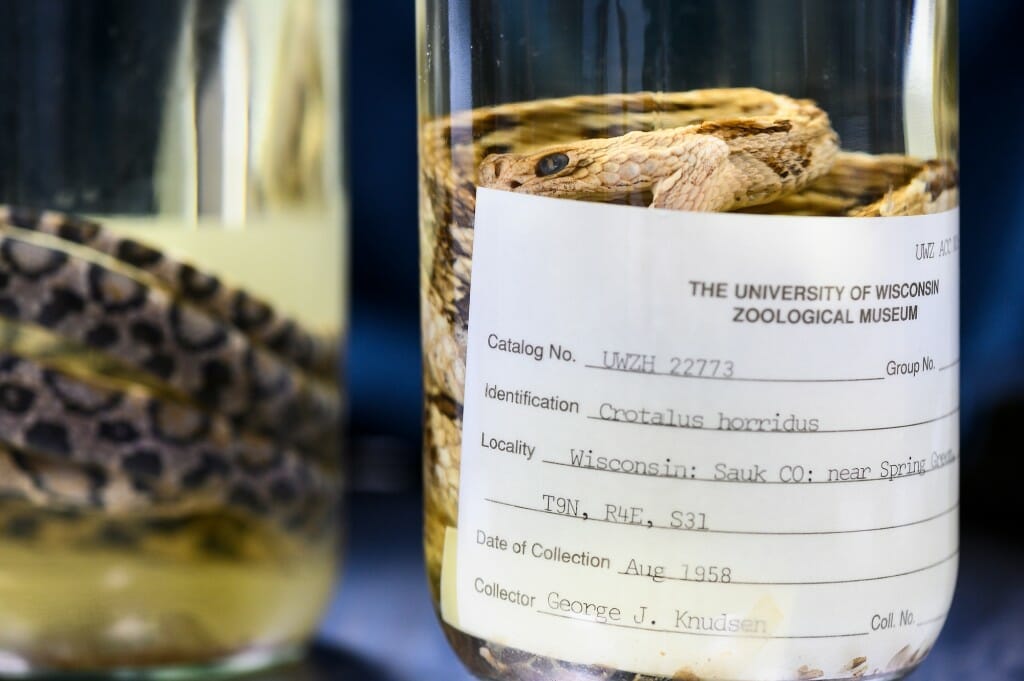

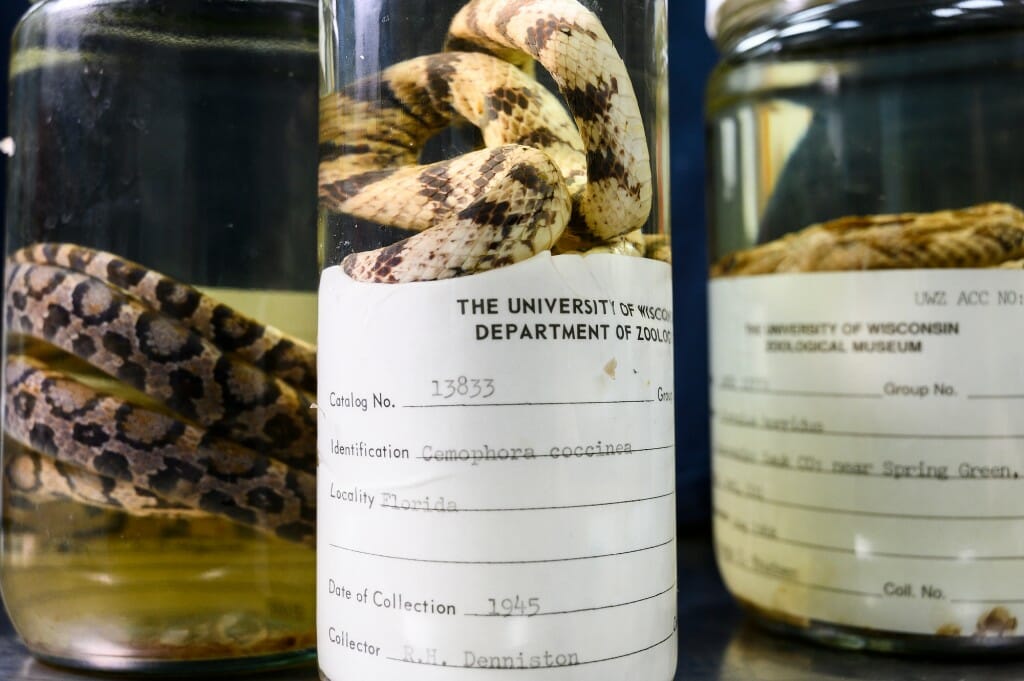

Lorch took thumbnail-sized skin samples from several, including six from UW–Madison. Three of those — a scarlet snake collected in Florida in 1945, a timber rattlesnake found in Wisconsin in 1958 and a gray rat snake from Tennessee circa 1973 — yielded tissue from which extracted DNA confirmed the presence of the fungus.

“That’s a wide distribution across the eastern U.S. Not just a single snake or place or time, and well before the disease was confirmed,” says Lorch, who published his findings this summer in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases. “It changes the way we consider the fungus, the direction we may take with research and management, and that’s thanks to museum collections like the one here at UW.”

There are more than 700,000 specimens — from tiny mussel shells to hulking hippo skulls — at the UW Zoological Museum, which makes them available on campus and loans them to institutions and scientists all over the world for teaching and research purposes like Lorch’s study, according to Laura Monahan, the museum’s curator of collections.

“They can’t go back in time to collect samples for their work,” Monahan says. “But we can preserve these snapshots in time. If they’re preserved well, there are so many things researchers can see in them.”

Lorch took samples from as early as 1929 from the Morehead State collection that looked like they had fungal infections, but those snake skins were not preserved in a way that would still give up DNA.

“You can still see the fungus in the layers of skin in the UW specimens. You can still see the cell structure,” he says. “It’s always amazing to me how well preserved these specimens are.”

That’s a tricky part of growing and maintaining museums like Monahan’s.

“The people who collected things we have from the 1800s didn’t know how we would use them. We don’t really know how they might be used in the future,” she says. “But we can be confident they will continue to figure in new science even as they age.”