UW researchers contribute to study of mammoth survival on tiny island

Remote St. Paul Island off the coast of Alaska was once part of the Bering Strait. Here, a population of mammoths outlived their mainland counterparts by several thousand years. Today, the island is home to a small Aleutian fishing village; seals, arctic foxes and caribou; and, as seen here, a weather station. Photos courtesy of Jack Williams and Yue Wang

Nearly 5,500 years ago, prehistoric human civilizations in the Fertile Crescent were flourishing, horses and chickens were being domesticated, and a population of island-dwelling woolly mammoths was surviving — thousands of years later than their mainland cousins — on a remnant piece of land once part of the Bering Strait land bridge.

According to a new study led by researchers at Pennsylvania State University, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), these mammoths were the second-to-last known surviving population in the world. The study provides clear evidence for their extinction around 5,600 years ago, likely driven by a lack of fresh water and changing environmental conditions on tiny St. Paul Island.

Model of a woolly mammoth on display at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, British Columbia. Photo: Flying Puffin via Creative Commons

John “Jack” Williams, professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and his graduate student Yue Wang, were significant contributors to the study and both say the information is relevant to small oceanic islands today and the people and animals that live on them. Wang says the study also has implications for understanding other prehistoric extinctions of large animals in other parts of North America, including the Great Lakes region.

“It’s a cool story in multiple ways,” says Williams, who is also director of the UW–Madison Nelson Institute’s Center for Climatic Research. “I can’t think of any other case where freshwater availability was the driver of extinction. On small oceanic islands, freshwater can be a limited resource.”

Jack Williams is bundled up to protect against extreme cold and wind during a winter season in the field on polar St. Paul Island.

For their part of the study, Williams and Wang examined vegetation changes that may have contributed to the mammoths’ extinction as well as fungal spores associated with the animals’ presence on the 110 square kilometer island off the coast of Alaska.

Williams traveled to the island in March of 2013 and stayed for 10 days. Strong storms whipped across the tundra and he and collaborators from across the U.S. hunkered down in a cabin with no phones and limited internet service.

They rode snowmobiles to one of the few sources of freshwater on St. Paul Island, a crater lake surrounded on three sides by steep rock walls. Wearing as many layers as possible, but thin gloves or none, Williams and his fellow scientists drilled through the frozen lake surface to take samples of sediments beneath the lake floor.

These sediments are snapshots of the lake environment through time, with each horizontal layer capturing a different period, and they allow scientists to study whatever materials settled into the lake hundreds or thousands of years ago, including fungal spores found in mammoth dung.

Their instruments kept freezing as they used them, Williams says, and they had to warm the meter-long steel tube apparatus used for taking sediment cores with rags dipped in boiling water. Other instruments had to be kept in the water to keep them above freezing.

To access the sediments at the bottom of a freshwater lake, the researchers had to drill down through the frozen surface like ice fishermen.

“(Study lead) Russ Graham and I would push the sediment mud into cling wrap and PVC tubes and wrap them up to keep them as clean as possible,” Williams says. “It was muddy and wet.”

Wang visited later, in July, and described the island as foggy and continuously saturated. “I wore my rain jacket the entire time,” she says. While there, she and her colleagues took vegetation and soil samples and visited with people in the small Aleutian fishing village on the island.

“There is a small school and a museum,” Wang says, adding that many people talked about the mammoth bones they’d found. The museum had several mammoth bones in its collection.

From their surveys, Wang and Williams learned that the vegetation — the grasses and small shrubs associated with arctic tundra — had changed little over the millennia, so was unlikely to have played a strong role in the animals’ disappearance. However, the lake sediments provided information that agreed with the findings of colleagues who were also on the scientific hunt for the animals’ extinction date.

“No single lab can do all of the analyses,” says Williams.

Overall, the study looked at five different indicators, or proxies, that showed when mammoths lived on — and disappeared from — the island. These included radiocarbon dating of mammoth bones on the island, Williams’ and Wang’s examination of three types of fungal spores associated with mammoth dung found in the lake sediments, and analysis of ancient DNA from mammoth remains on the island.

Lake Hill Lake, pictured when Yue Wang returned to the island in July, supported what is believed to be the second-longest surviving populations of mammoths in the world.

All of the proxies converged on an extinction date of roughly 5,600 years ago. Meanwhile, mainland mammoths went extinct from mainland Asia and North America by roughly 10,000 years ago.

“Every proxy has ambiguity and challenges and no single one is a certain truth,” Williams explains. “We had five independent indicators. That’s pretty remarkable.”

The research team, through other proxies, found evidence of dwindling freshwater on the island, including clues that water became more brackish around the time of extinction, the lake became more shallow, more water was evaporating from the island, and the watershed experienced increased erosion — perhaps caused by the mammoths themselves.

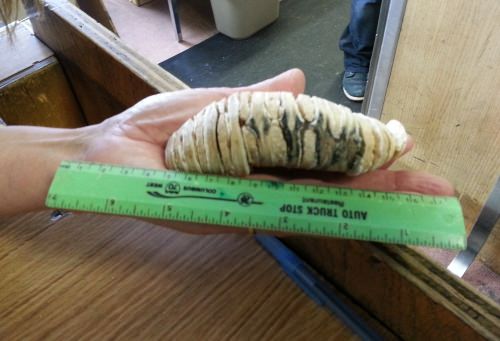

Mammoth teeth, like this one found on St. Paul Island, are large and built for grinding vegetation like coarse tundra grass.

Elephants, relatives of the woolly mammoth, consume as much as 200 liters of water per day, so mammoths likely also required large volumes of clean, fresh water to survive.

Williams says there is nothing to indicate humans lived on or came into contact with the island, and even today, Wang says with a laugh, there are more seals than people.

Wang is now working with Warren Porter, UW–Madison professor of zoology, on reconstructing the environment and landscape of St. Paul Island in the time of the mammoths, using data from the new study and other sources.

“We want to model the island as it was when the mammoths existed on it,” says Williams. “We want to learn the carrying capacity of the island, their population numbers, their dietary and water requirements.”