UW–Madison economist publishes book on U.S. financial crisis

In the summer of 2007, University of Wisconsin–Madison economist Menzie Chinn was among those who started to think something was amiss with the U.S. economy.

Mortgage-backed securities were little-understood financial instruments, but Chinn remembers red flags going up as certain measures indicated that the AAA-rated versions of these securities were losing value.

“That was a first and that started people worrying,” he says. “From that point onward, it was a slow-motion train wreck.”

As the economy stumbled the next year, Chinn, professor in the La Follette School of Public Affairs and Department of Economics, and Harvard University political scientist Jeffry Frieden started trading emails in an effort to make sense why the financial boom had fizzled.

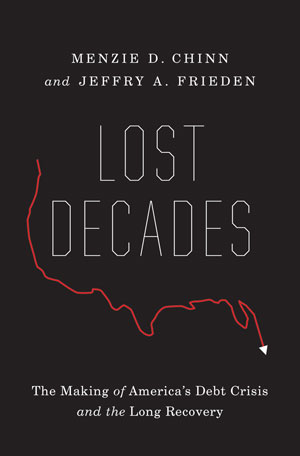

Their emails have grown into a book, “Lost Decades: The Making of America’s Debt Crisis and the Long Recovery,” which will be published today (Sept. 19) by W.W. Norton & Co.

Together, the pair has more than 50 years of experience evaluating debt crises and studying financial and currency meltdowns in Europe, Latin America, Asia and Russia. They drew on that to evaluate what happened in the U.S. in the past decade.

“We have watched country after country lose decades of economic progress to the austere aftermath of financial crises,” they write in “Lost Decades.” “But we never feared that we would see a classic debt crisis in our own homeland. And we never imagined that our country could face the prospect of almost two decades lost to misguided policies, an unnecessary crisis and a daunting task of economic reconstruction.”

Experts who have read the book call it “an intelligent, vivid and accessible account of the first great crisis of the 21st century” and “an integrated and compelling account of where our debts came from — and why they won’t go away any time soon.”

But “Lost Decades” isn’t intended to be merely a prescription, Chinn says.

“We didn’t want to say what you should do, we wanted to ask, ‘What got us into this mess?’” he says. “The more we got into this, the more we realized what you decide to do going forward depends on how you think we got to where we are now.”

Many of the lessons chronicled in Chinn and Frieden’s book aren’t new. The book opens with an anecdote that leads readers to believe it took place in recent years, but in fact tells a parallel story from 1938, when the U.S. was still trying to bounce back from the Great Depression.

“As was the case in the late 1930s, the causes and consequences of the crisis are hotly debated,” Chinn and Frieden write in the book. “And just as then, a great deal rides on an appropriate understanding of why and how the United States got to where it is today.”

For the authors, the crisis had its roots in a toxic mix of a easy access to foreign savings, the rise of a no-regulation ideology applied to the financial system and the belief that government can run big budget deficits to finance tax cuts for the rich and wars abroad, even during good economic times, with impunity.

Heeding the kinds of warning signs the pair started to see in the summer of 2007 is difficult because politicians have a hard time believing government might need to intervene to prevent a crisis when all seems well on the surface, Chinn says.

“That’s a hard thing to push for when all you can say is, ‘I think we’ll have trouble if we don’t cool it down now,’” Chinn says.

The U.S. is still feeling its way out of the financial crisis, which Chinn says holds lessons for the nation going forward, both now and in the coming years.

“We need to get in place a framework for cutting the deficit going in to the next decades, and that entails dealing with entitlements in painful ways and raising tax revenues relative to where they are now,” he says. “But the short-term challenge is to stimulate the economy. As we see certain politicians call for big and immediate cuts in discretionary spending, even as the economy is sputtering, it appears that the lesson from 1938 — that an overly eager fiscal and monetary retrenchment can lead to a relapse — has been forgotten.”