Talking to doctors: Never simple, but getting tougher: Could this help?

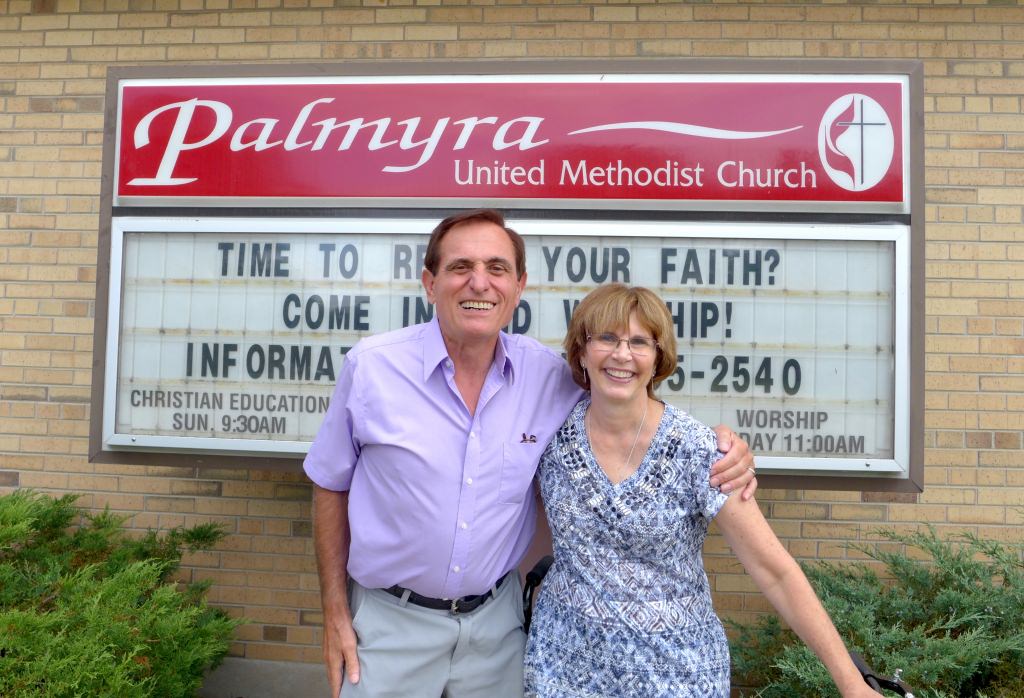

Nick Argeroudis of Oconomowoc and Lee Clay of Mukwonago co-taught the class in Palmyra. “As a retired hospital executive, I know that improving communication between patients and providers is critical for improving healthcare in the community,” says Argeroudis. David Tenenbaum, University Communications

PALMYRA, Wisconsin – Whether it’s the baroque language, the obscure diagnoses or the impenetrable bills, medicine is growing ever more complex. What information and strategies could help a relative caring for an elder with heart disease, Alzheimer’s or dementia cope with the medical system?

A desire to answer that deceptively simple question explains why eight women are discussing a program called Care Talks in the social hall of the Palmyra United Methodist Church on a sunny August morning.

Four have already “graduated” from the four-session program; the other four plan to start soon.

UW-Madison professor of family medicine Paul Smith is leading the development and testing of Care Talks. He says that the need to improve communication with the medical system arose as the cardinal need in a 2011 survey of Green County people caring for adults who are older than 60.

And so in 2013, Smith says, he began to develop a way to “build on current communication skills and provide some additional skills.” Care Talks is a set of four two-hour workshops for caregivers that “offer problem-solving methods for communication with the health care system,” including receptionists, nurses, physician assistants, doctors, pharmacists and physical therapists.

Care Talks is being tested at five sites in Wisconsin, including Palmyra, just east of Whitewater. The project, part of the Community-Academic Aging Research Network at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, operates through local Aging and Disability Resources Centers.

Smith’s study is comparing trained adults to those who have yet to begin the training. “We are measuring the impact on the caregiver, and on the health and health outcome of the care partner,” he says. “We are tracking physician office visits, hospitalizations, falls and medication errors, among other things.”

The analysis is not finished, but the four Care Talks “alumni” at Palmyra seemed impressed (Their names aren’t used here for privacy reasons).

“You are a consumer, and part of your job is to make sure you are getting what you need.”

Lee Clay

“It’s helped tremendously,” says “Ann.” “If I don’t understand, I ask the doctor to please repeat. Now I ask for them to write out unfamiliar terms and drug names.”

Ann has become an evangelist for the program. “When people ask, I say, ‘We are learning how to speak to doctors, and to know who all the people are that come before the doctor, and why it’s important to fill them all in on everything.’”

Communication between the caregiver and the “care partner” can also benefit. One member said she’d tried to get the doctor to raise an uncomfortable issue with her husband. “I called before the appointment, said I thought he was getting depressed. I wanted the doctor to ask how he was doing, and they did address that. Without that suggestion from Care Talks, I would not have done that.”

“Margaret” was discussing a complicated medical situation with her husband, but could not get him to budge on an issue she thought important. “I love him to death,” she says, “but I can’t help him if he’s not going to help himself. I said, ‘You are scaring me.’”

Group co-leader Lee Clay, who spent a decade as a parish nurse, offered a different approach: “Next time, hold his arm, look him in the eye, and say, ‘I’m really concerned.’”

The group conversation showed how it had cemented into a support group for people dealing with chronic health problems. Clay stressed the need to take an active posture with the medical system. “You are a consumer, and part of your job is to make sure you are getting what you need.”

An active attitude does not assume that every doctor – or every doctor-patient relationship – is ideal, said co-leader Nick Argeroudis, a retired hospital executive. “It’s okay to fire your doc. If the doctor is not communicating with you, if you feel like you’re mixing like oil and water, go to another doctor.”

Clay operates a business called Prevent Health Strategies and considers herself well-versed in the medical system. She found a personal benefit from the ideas she was teaching after her mother phoned from a rehab facility at 2 a.m., complaining that nobody was answering her call button. Clay raised the issue with an administrator the next day, and “could see she wanted a fight, so I used the language strategy I was teaching: ‘I am concerned about this. I hope it doesn’t happen again. In the future, what I want to see is…’.”

“It worked like a charm,” Clay says, “and we established a system to avoid a repeat. When I started teaching Care Talks, I thought this was great in theory, but I was going to prove them wrong … but they weren’t.”

Subscribe to Wisconsin Ideas

Want more stories of the Wisconsin Idea in action? Sign-up for our monthly e-newsletter highlighting how Badgers are taking their education and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom to improve lives.