Students find inspiration in class merging science and art

Artist in Residence Peter Krsko discusses student projects while teaching a class, Zoethica: Bioinspired Art and Science, at the Agricultural Engineering Laboratory. Photo: Jeff Miller

Peter Krsko hauled 800 feet of hosing through the woods, drilled holes into the trees on his property in Wonewoc, Wisconsin, and for the first time, tapped his maples for the sap that will ultimately become maple syrup.

While he was laboring, Krsko began to contemplate how trees fight gravity and move fluid from their roots deep in the ground to leaves and buds in the sky. That got him thinking about cells, the basic conduits of those fluids, and how they pack together to build the tissues and organs found in living things.

“I wanted to share with you what I was doing this weekend, what I was thinking about while I was drilling holes,” the artist, scientist and educator explained to his class at the University of Wisconsin–Madison on a recent February afternoon after his first tapping.

Krsko chose the name Zoethica “to explore bioinspired art and technology, not only from the aesthetic and scientific point of view, but also to explore the ethical implications.”

That class, called Zoethica: Bioinspired Art and Science, is part of Krsko’s semester-long commitment to UW–Madison as the Art Institute’s spring Interdisciplinary Artist in Residence. Krsko chose the name Zoethica, a combination of the Greek word for life (zoe) and the word ethical, because his goal during his residency is “to explore bioinspired art and technology, not only from the aesthetic and scientific point of view, but also to explore the ethical implications.”

Krsko’s residency is hosted by the Department of Biological Systems Engineering, with Sundaram Gunasekaran as lead faculty, along with the departments of art and physics and the School of Human Ecology.

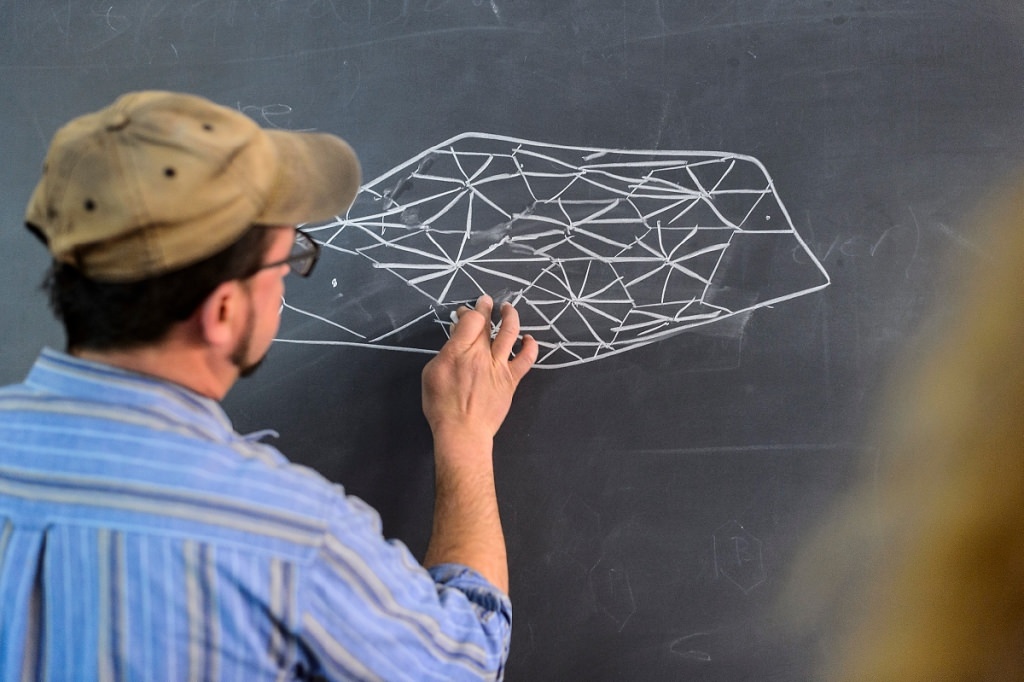

Krsko sketches a chalk design of a biologically based structure. Photo: Jeff Miller

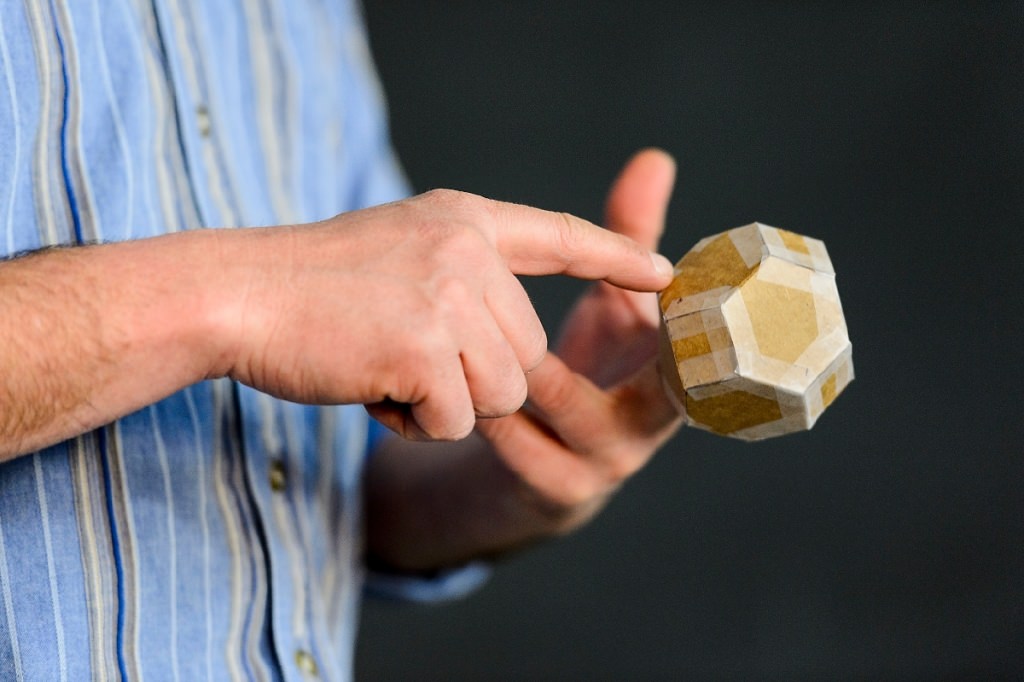

Krsko used his tapping experience to discuss with his students the efficiency with which nature packs individual units like cells in the body or the hexagonal cavities found in a honeycomb.

“I like to trick people into thinking about things that are all around us but are invisible,” he said, passing around three-dimensional paper shapes and holding up a dried wasp nest.

That means challenging students to consider aspects of the world they may never have considered. It’s part of his quest to find ways to make science accessible to all and to inspire natural curiosity about the world.

“I like to trick people into thinking about things that are all around us but are invisible.”

Peter Krsko

For instance, on this afternoon, students had brought in handheld, three-dimensional shapes made of wooden sticks and held together with colorful rubber bands. In these tensegrity structures, Krsko explained, the sticks are held together in formation solely due to the tension created by the rubber bands. He drew a parallel between these and the human skeleton, which is similarly held together through the tension of ligaments and tendons.

Freshman Leo Steiner was eager to demonstrate the tensegrity structure he had built with six sticks and six rubber bands after finding a design online. Soon, a handful of students were clustered around his desk, working to recreate the structure.

Undergraduate Leo Steiner, second from right, enlists the help of classmates to construct a tensegrity model — a structure held together using isolated floating compression. Photo: Jeff Miller

Steiner, a UW–Madison biomedical engineering major, enrolled in the course after his father saw it in a pamphlet. “I am interested in how nature is applied to new technology, and I think art has a way to inspire,” he said.

Biological Systems Engineering is hosting an artist for the first time, and Gunasekaran said he is glad students in the department have the opportunity to engage with and get excited about biological materials.

Because Zoethica is an experience in inspiration. Students are tasked with reviewing literature from a breadth of disciplines to arrive at answers to questions posed by Krsko, or those they come up with organically as they progress through the class.

It’s part of his quest to find ways to make science accessible to all and to inspire natural curiosity about the world.

For example, one student wondered out loud why there are no wheels to be found in nature. Krsko challenged him to solve the puzzle.

“He had to figure that out, looking at the literature in biophysics, evolution, biology, to arrive at an answer to why it is not possible for animals to have wheels,” Krsko said.

Krsko holds a cardboard model of a Weaire-Phelan structure. Photo: Jeff Miller

For Krsko, art is the expression and process of inspiration. Originally from Slovakia, Krsko moved to Wisconsin a year ago from Washington, D.C. He holds a Ph.D. in biophysics and trained as a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institutes of Health studying bacterial biofilms, with a particular focus on their microscopic patterning and properties.

The visual nature of his science and his passion for education melded into a career fusing art, science and outreach. In particular, he believes the hands-on, creative nature of art helps make science more accessible and he is passionate about working with underrepresented students in their communities.

“I am interested in how nature is applied to new technology, and I think art has a way to inspire.”

Leo Steiner

“Some kids don’t have the same opportunities to access science, and I focus on that,” Krsko said. “There is so much talent hidden in places that have never had the chance to shine.”

This is why he creates community art for public spaces, like the six-foot by six-foot project he is creating for the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery, or the columns of upward-splaying wood he recently built in the atrium of Birge Hall, inspired by a greenhouse tour provided by a botany graduate student in his class, Evan Eifler.

Krsko looks over his plans for creating a botany-inspired art installation in Birge Hall. Photo: Jeff Miller

Zoethica students are all working on independent, bio-inspired art projects, which they will exhibit in a final show at Olbrich Botanical Gardens in Madison on May 5. (The show will run through August.) They are building a public-facing website to share their efforts, and Krsko will use the experience to create middle school science and art curricula for teachers around the state and the world.

Krsko is a natural creator. From making his first maple syrup, to gardening and producing wine, Krsko uses the natural world, and the lessons nature offers, to examine processes and create tangible products — including, as it were, educational opportunities.

Krsko is passionate about working with underrepresented students in their communities.

Back in the classroom, a large space in the Agricultural Engineering Laboratory, Krsko helped Rebecca Green, a senior French and neurobiology major, polish her independent project: embedding a Play-Doh neuron in a matrix of silicon rubber to simulate the microscope images she takes in the laboratory in which she works. Green studies how stress affects memory, and she wanted to create a three-dimensional model of these images. She may be able to use it at a scientific conference in April.

“I’m pretty excited because it’s relevant to what I am doing in lab,” Green said. “I figured it’s a good exercise in communication, melding science and art. I want to go into the medical field and I thought it would offer problem solving in a different way.”

Krsko wraps one of the lobby columns in Birge Hall with wooden lattice. Video: Jeff Miller

Meanwhile, senior Kayla Pfeiffer–Mundt, who is pursuing a master’s degree in public health in the fall, was working with Eifler to set up a time-lapse video of a slime mold growing in search of food, bits of granola placed strategically around a glass plate. Pfeiffer–Mundt hopes to model the spread of infectious disease using the slime mold. If she can work out the hurdles, she plans to place bits of granola over major cities on a map of the world and watch the slime mold grow.

Krsko is enthusiastic about working with students for an entire semester, and he hopes they learn and grow from the experience.

For Eifler, the class has served as an inspiration for him to do more to communicate science with nonscientists. He saw the large, open atrium of Birge as an opportune spot for the column art project, which he helped Krsko install.

“I’m pretty excited because it’s relevant to what I am doing in lab. I figured it’s a good exercise in communication, melding science and art.”

Rebecca Green

“As scientists we don’t often get to host art installations,” Eifler said. “I wanted to think outside the box because we scientists tend to stay in our spaces.”

Eifler’s Ph.D. work is focused on the evolution of plants in South Africa but he’s also pursuing a minor in science communication. The course has been a pivot from that rigor: “I feel mentally relieved here, he said, “because I get to think about something entirely different.”

Which is exactly what Krsko is hoping for over the course of his residency.

“We still have a lot to learn from nature,” he said.

• • •

Zoethica opening May 5, 5-9 p.m. at Olbrich Botanical Gardens, 3330 Atwood Ave., Madison

Tags: arts, science, visiting artists