Specimens from George Washington Carver discovered at UW-Madison

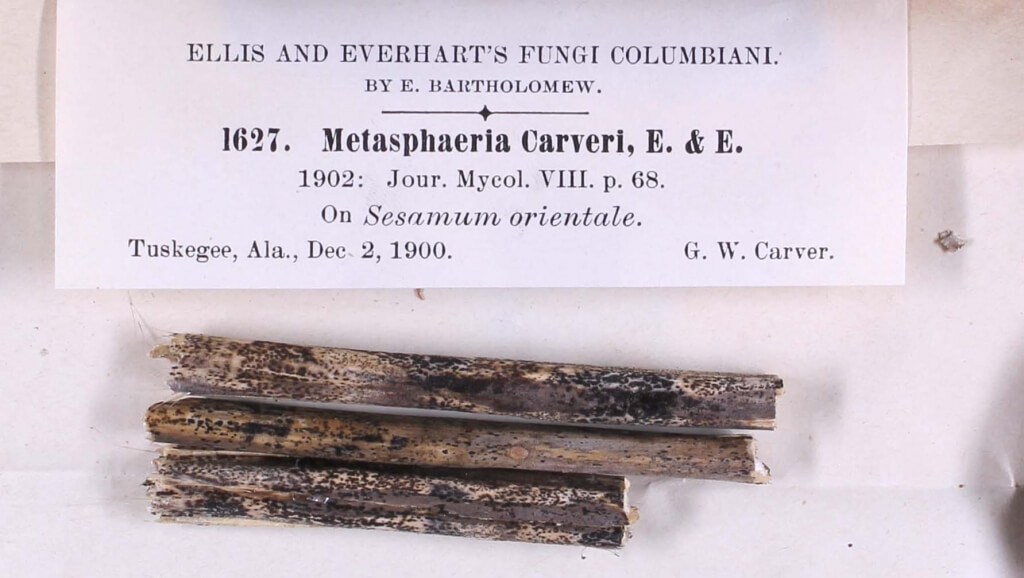

This sample of a microfungus, collected in Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1900, was discovered at the Wisconsin State Herbarium on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus. The specimen was named for its collector, George Washington Carver. Photo: Wisconsin State Herbarium

At least 25 specimens of fungi that infect plants, collected by George Washington Carver more than a century ago, were discovered Feb. 8 in the Wisconsin State Herbarium at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The herbarium holds the nation’s second-largest collection — as many as 120,000 specimens — of “microfungi,” a type of fungus that does not form a mushroom.

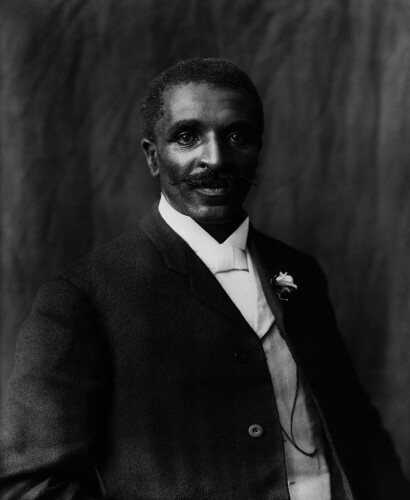

Carver (c. 1864-1943) was a prominent African-American scientist with a long record of achievement. Born a slave in Missouri, he became the first black student at what is now Iowa State University, then its first black faculty member. He spent 47 years directing agricultural science at the Tuskegee Institute, which was established during Reconstruction to educate blacks.

Although best known for his research on, and advocacy of, peanuts as a profitable, nutritious crop for southern farmers, Carver had many other interests, including the collection of microfungi.

Indeed, Louis Pammel, his professor at Iowa State, was a fungus specialist, and Pammel’s name appears on some of the samples just uncovered in Madison.

Although microfungi lack eye appeal, they are responsible for some of the most catastrophic agricultural epidemics, most notably the blight that caused the Irish potato famine, which killed millions starting in the 1840s.

The Wisconsin State Herbarium, started along with the university in 1848, now houses more than 1.2 million samples of plants, fungi and lichens. Herbarium specimens are used to identify species, track their changes through time, and to identify disease.

The herbarium’s reputation for excellence may have induced Carver to send samples to Madison.

Until a significant expansion of cabinet space at the herbarium in 2015, “the microfungi collection was sitting unappreciated for, I’m guessing, 50 years, in old wood cabinets in the hallway,” says herbarium director Ken Cameron.

The National Science Foundation financed the new cabinets and is also funding an ongoing databasing of 37 national fungus collections, including the large one at Madison.

During the digital upgrade, students photograph each sample’s label and enter its text into a database that goes almost immediately online. On Feb. 8, a database user in North Carolina emailed the herbarium to ask whether an Alabama fungus was mistakenly entered as originating in Alaska.

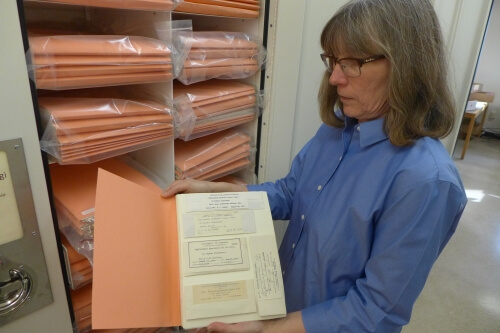

The same day, while checking the sample, Carver’s name was noticed, says herbarium curator Mary Ann Feist. Combing through the new database revealed a total of 25 Carver samples. With roughly 100,000 samples remaining to be processed, that number will likely rise.

Cameron notes that the Carver find is only the latest historical resonance to emerge from the herbarium’s vast collection. In 2014, curators found a note on an 1864 sample collected during the Battle of Atlanta observing that the specimen was “stained with the blood of (Union army) heroes.”

Mary Ann Feist, curator at the Wisconsin State Herbarium, with folders holding the George Washington Carver plant disease fungus samples discovered Feb. 8, 2016, ready for databasing. Photo: David Tenenbaum

The discovery of fungal samples collected by Carver did not surprise William Jones, a professor of history at UW–Madison who teaches about the civil rights movement. “At Tuskegee, he studied blights as well as agricultural techniques and established agricultural stations to train black farmers in agricultural technology. This is similar to what UW-Extension does: empowering farmers with the knowledge to help them succeed.”

History’s perspective on Carver has changed, says Jones. In the late 1800s and early 1900s he, like Tuskegee founder Booker T. Washington, was considered a paragon of the race — a symbol of achievement for the newly freed slaves and their descendants.

Carver and Washington were relentlessly practical and apolitical, Jones says. “Washington was famous for believing that training African-Americans and giving them skills would allow them to establish financial independence, and he very pointedly did not criticize political restrictions on the freed slaves. In his view, it was more important to be economically independent.”

During the early 1900s, Washington and Carver, who Jones calls “Washington’s most important ally,” clashed with more assertive African-Americans like W.E.B. Du Bois.

Although the confrontational approach was later celebrated during the Black Power era of the 1960s and ’70s, today Carver can again be seen as a symbol of scientific and social accomplishment, Jones says. “He represented a marriage of scientific knowledge and popular education for economic empowerment. One can look at what Carver was doing and see that it clearly benefited, in really concrete ways, the lives of millions of people.”