Runge sees bioenergy hub as model for doing ‘big research’

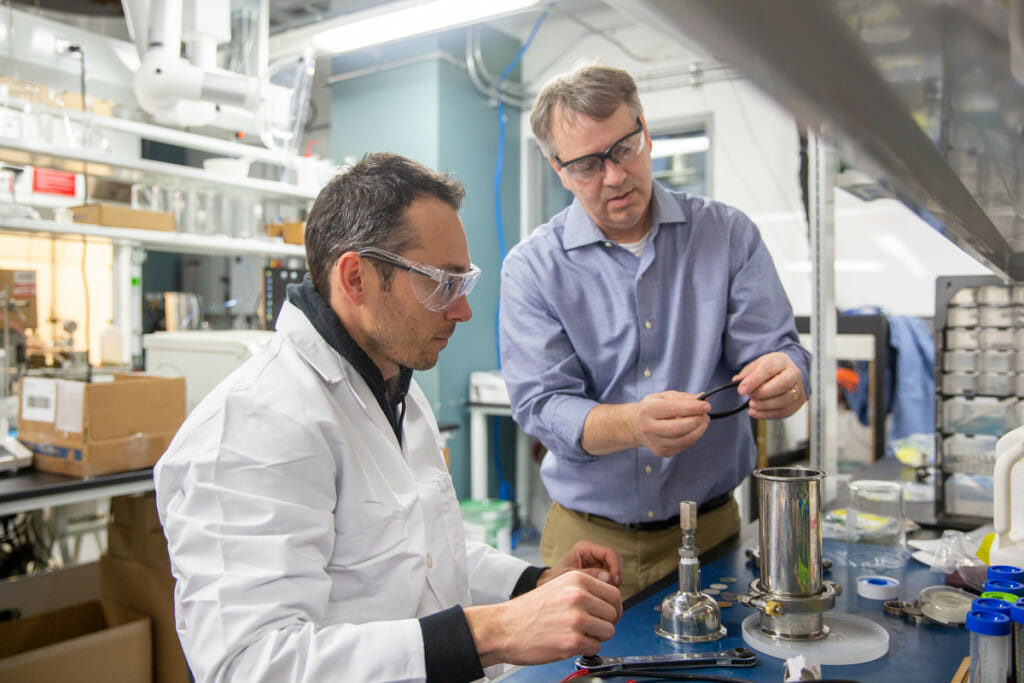

Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center co-investigator Troy Runge, right, discusses engineering concerns with postdoctoral researcher Jordi Francis Clar in Runge’s lab at the Wisconsin Energy Institute. Runge, the new associate dean for research of the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, hopes to inspire more interdisciplinary collaborations like GLBRC.

When it comes to helping Wisconsin residents and the state’s economy, you Can’t Stop a Badger. See how UW–Madison scientists conduct cutting-edge research and outreach programs that deliver tangible benefits for Wisconsinites and the world. Follow along using #CantStopABadger on social media. Your support can help us continue this work.

Troy Runge grew up around silos. As the new director of agricultural and life science research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he’s hoping to tear some down.

An academic with a background in two of Wisconsin’s biggest industries, Runge wants to create opportunities for collaboration within the institution and foster collaboration with partners in the private sector.

“I don’t see business as all that different from science,” Runge says. “What we do (in academia) has much more freedom, but at the end of the day we’re all trying to solve problems. We’re trying to make the world better.”

A first-generation college student, Runge grew up on a dairy farm and spent a decade and a half in the paper industry before joining the university, where he is a professor of biological systems engineering.

Runge took over on April 1 as the associate dean of research for the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, or CALS, where he oversees a $166 million research portfolio that includes food systems, human health, ecosystems, climate change and economic development.

GLBRC scientist Steven Karlen, left, shows co-investigator Troy Runge phenolic extracts of poplar wood in Runge’s lab at the Wisconsin Energy Institute. The research hub is investigating ways to convert the viscous oil, often treated as waste, into plant-based replacements for chemicals currently derived from petroleum.

In that new role, he hopes to develop interdisciplinary research hubs like the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, where he leads a team working to develop cost-effective methods for turning plants into low-carbon replacements for fossil fuels and petrochemicals.

“I want to use my experience promoting our research and developing research initiatives to accelerate ideas that can improve the lives of the people of Wisconsin and beyond,” he says.

Brian Fox, professor of biochemistry and chair of the associate dean hiring committee, says Runge stood out for his corporate management experience in addition to his academic resume and 31 patents.

“Coming from industry and now having been in academia, he’s kind of seen both sides,” Fox says. “He appreciates the good things both sides can bring to the table and the inherent constraints on both sides of the operation.”

Raised in Marathon County, where the farm fields of southern Wisconsin meet the pine forests of the northwoods, Runge got his first taste of science and engineering on his family’s small dairy farm.

“We called it playing, but it’s not so different from what we do in the lab — taking things apart and putting them back together,” he says. “Obviously we’re a little higher tech.”

After graduating from Colby High School during the 1980s farm crisis, when farmers across the Midwest were losing their land and livelihoods, Runge was encouraged to go to college and land a job with better economic security.

Knowing he’d still need to help on the farm, he enrolled at the nearby University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, where he majored in paper science and engineering.

“I knew cows, and I knew trees,” Runge says. “I didn’t like getting up early, so it was trees.”

He landed an internship with Kimberly-Clark, the maker of household products like Kleenex, Huggies and Kotex. At the mill, he saw bales of eucalyptus pulp transformed into tissue paper and was hooked.

On the advice of his boss, Runge later enrolled in graduate school on an industry scholarship, eventually earning a PhD in wood chemistry from Georgia Tech University.

Runge returned to Kimberly-Clark, where he worked on big problems, like how to make paper pulp less toxic. He was drawn to the idea that science wasn’t just about ideas — it could also have an immediate impact on people’s lives.

“It wasn’t at the institution. It was at K-C,” Runge says. “That’s where I really grew to love science.”

Runge rose to research director, a job that put him in charge of hundreds of scientists but also exposed him to some of the limitations of corporate research.

“There are some things you should do because they’re good ideas,” he says. “That’s hard when you have shareholders.”

In 2009, craving more academic freedom and a chance to be closer to home, he joined UW–Madison as director of the Wisconsin Bioenergy Initiative, a clean energy research program established in 2007 to complement the federally funded Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center.

As a co-investigator at GLBRC, Runge has applied his knowledge of wood chemistry to a different problem: breaking apart the tough matrix of molecules known as lignin that give plants their structure.

Cracking that nut is key to converting plants into sustainable replacements for jet fuel, diesel and gasoline as well as extracting hydrocarbons that can be turned into products currently derived from petroleum, like polyester and nylon.

Troy Runge, professor of biological systems engineering in CALS, and his research team, Steve Karlen, Jason Coplien, and Jordi Francis Clar, fill a pressure reactor with solution in the lab.

That could in turn create economic development opportunities for struggling Wisconsin industries like paper mills, where more than two-thirds of the jobs disappeared over the last two decades, and farms.

In his new role, Runge hopes to develop more research hubs like GLBRC, which brings together biologists, chemists, engineers, agronomists and other experts from multiple institutions who wouldn’t normally have an opportunity to collaborate on holistic solutions to one of society’s most daunting problems.

Runge says that should be the model for doing “big science.”

“It’s the very definition of synergy,” Runge says. “I think this is some of the most impactful science that our faculty can be involved in.”

Runge himself plans to stay involved in that science: In addition to his new role as associate dean he will continue running his GLBRC lab.

Jennifer Gottwald, director of licensing for the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, says Runge’s knowledge of industry and collaborative approach hasn’t just influenced his own research.

“He talks to so many other researchers on campus and is respected and credible for his industry perspective,” Gottwald says. “He helps other people’s research by meeting them where they’re at, telling them things they might not have thought about as basic researchers.”

Subscribe to Wisconsin Ideas

Want more stories of the Wisconsin Idea in action? Sign-up for our monthly e-newsletter highlighting how Badgers are taking their education and research beyond the boundaries of the classroom to improve lives.