Quick, routine coronavirus testing reassures both campus and volunteers

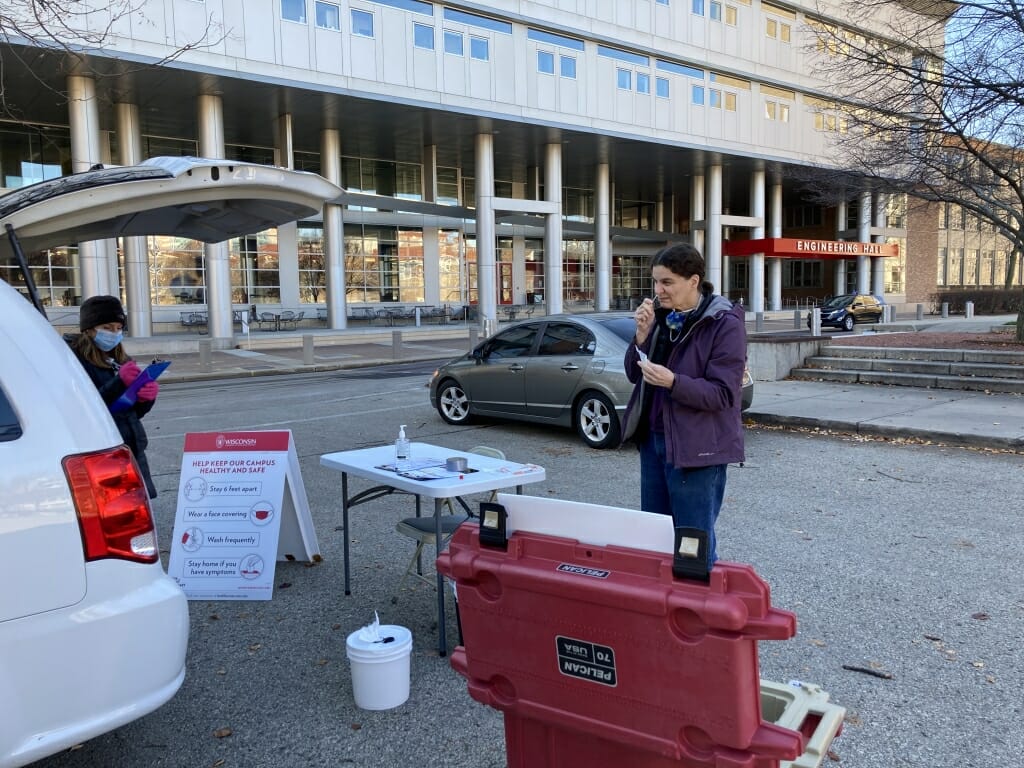

Bacteriology researcher Tanya Falbel prepares a COVID-19 sample near Engineering Hall as Katie Reisdorf looks on to make sure the swab was prepared correctly. Photo: Mary Checovich

Once a week, perhaps on his lunch break or during an afternoon stroll, Jon Temte stops by a pop-up kiosk on campus, swabs both his nostrils, and drops off his weekly COVID-19 test for analysis as part of a coronavirus surveillance program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“From my own experience, this process takes two to three minutes,” Temte says. “It’s very simple and quick.”

Temte isn’t just a volunteer with the program. He’s also its architect. For almost 30 years, Temte, a professor and dean in the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, has led research projects tracking and predicting the spread of respiratory illnesses. Now, he has turned his attention to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

As SARS-CoV-2 began to spread around the country last spring, Temte knew there was an opportunity to learn about this new virus and provide critical information to the 65,000-plus-member campus community as it navigated operations in the pandemic.

With around 500 staff and graduate student volunteers who submit weekly samples for COVID-19 testing, Temte’s surveillance program keeps a pulse on the health of on-campus workers as operations have ramped up. Unlike other testing on campus, which is more likely to attract people who are sick or who believe they’ve been exposed to COVID-19, Temte’s program constantly re-tests a stable population of volunteers — even when they feel fine.

That consistent population helps the surveillance project answer different questions.

“We’re able to provide information that nobody else can: How many individuals that are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms that are coming to work on campus have the potential to spread SARS-CoV-2?” says Temte, who has worked in his campus office most days since March. “And at least so far, we can provide assurance to faculty and staff that this is a pretty safe place to be. We have far less concern on campus than we do in the broader community.”

In recent weeks, the infection rate in the program has been very low, about a quarter of one percent. Research spaces have been able to remain open, though density in campus buildings is reduced.

Such consistent testing has also offered participants peace of mind.

“Because I’m going on campus part of the time I thought this was a great way to do a surveillance check — and a safety check for my family, because I want to protect them as well,” says Kasia Novak-Janus, a research animal compliance specialist who works on campus a couple days a week now. “It puts my anxiety at ease when I get tested every week.”

Austin Salome, a first-year graduate student in chemistry, signed up for the program because he shadows senior graduate students on campus to decide which lab to eventually join. He prompted his roommate and others in his graduate program to join the surveillance project as well.

“The staff are really nice, and they also make it really easy. I don’t think I’ve ever waited more than five minutes to get tested,” says Salome.

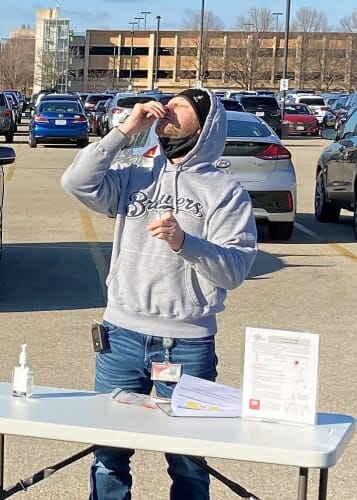

Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory pathologist Daniel Barr swabs his nose in Lot 60 to prepare a sample for COVID-19 testing as part of an ongoing surveillance program on campus. Photo: Mary Checovich

The program only notifies participants if they test positive, which Salome says helps put him at ease. With other testing, “I found that I had a lot of anxiety, because I knew I was going to get a result back, but you never know if it’s negative or positive. Whereas with this, you’re just not going to get a result unless it’s positive, which I think is really nice, because I don’t worry about it.”

The surveillance project has steadily increased the number of participants, with the goal of testing around five percent of the on-campus employee and graduate student population every week. They are looking to add volunteers, and interested staff can learn how to join by visiting the project’s website.

To date, Food and Drug Administration certification requirements have meant that volunteers must swab their noses in the presence of trained staff to ensure they produce a quality sample. But the program is applying for FDA approval to move to unobserved sampling. If approved, the project could expand to over 1,000 participants because sampling would be easy enough for volunteers to do on their own and simply drop off.

That expansion could not only help campus stay safe but also provide a growing number of volunteers with confidence that their own risk-reduction behaviors are working.

“I think many of us across campus try to be very safe in our usual activities. However you can’t be totally sure you don’t encounter this virus,” says Temte. Such routine testing “provides the reassurance that I have not encountered this virus without my knowledge.”