Physicists find way to ‘see’ extra dimensions

Peering backward in time to an instant after the big bang, physicists at the University of Wisconsin–Madison have devised an approach that may help unlock the hidden shapes of alternate dimensions of the universe.

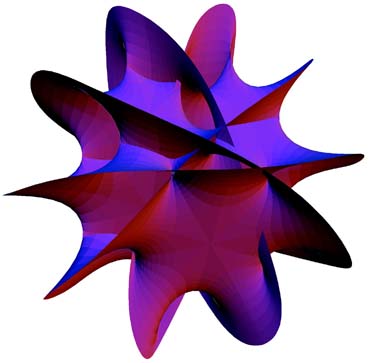

A computer-generated rendering of a possible six-dimensional geometry similar to those studied by UW–Madison physicist Gary Shiu.

Image: courtesy Andrew J. Hanson, Indiana University

A new study demonstrates that the shapes of extra dimensions can be “seen” by deciphering their influence on cosmic energy released by the violent birth of the universe 13 billion years ago. The method, published today (Feb. 2) in Physical Review Letters, provides evidence that physicists can use experimental data to discern the nature of these elusive dimensions — the existence of which is a critical but as yet unproven element of string theory, the leading contender for a unified “theory of everything.”

Scientists developed string theory, which proposes that everything in the universe is made of tiny, vibrating strings of energy, to encompass the physical principles of all objects from immense galaxies to subatomic particles. Though currently the front-runner to explain the framework of the cosmos, the theory remains, to date, untested.

The mathematics of string theory suggests that the world we know is not complete. In addition to our four familiar dimensions — three-dimensional space and time — string theory predicts the existence of six extra spatial dimensions, “hidden” dimensions curled in tiny geometric shapes at every single point in our universe.

Don’t worry if you can’t picture a 10-dimensional world. Our minds are accustomed to only three spatial dimensions and lack a frame of reference for the other six, says UW–Madison physicist Gary Shiu, who led the new study. Though scientists use computers to visualize what these six-dimensional geometries could look like (see image), no one really knows for sure what shape they take.

The new Wisconsin work may provide a long-sought foundation for measuring this previously immeasurable aspect of string theory.

According to string theory mathematics, the extra dimensions could adopt any of tens of thousands of possible shapes, each shape theoretically corresponding to its own universe with its own set of physical laws.

For our universe, “Nature picked one — and we want to know what that one looks like,” explains Henry Tye, a physicist at Cornell University who was not involved in the new research.

Shiu says the many-dimensional shapes are far too small to see or measure through any usual means of observation, which makes testing this crucial aspect of string theory very difficult. “You can theorize anything, but you have to be able to show it with experiments,” he says. “Now the problem is, how do we test it?”

He and graduate student Bret Underwood turned to the sky for inspiration.

Their approach is based on the idea that the six tiny dimensions had their strongest influence on the universe when it itself was a tiny speck of highly compressed matter and energy — that is, in the instant just after the big bang.

“Our idea was to go back in time and see what happened back then,” says Shiu. “Of course, we couldn’t really go back in time.”

Lacking the requisite time machine, they used the next-best thing: a map of cosmic energy released from the big bang. The energy, captured by satellites such as NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), has persisted virtually unchanged for the last 13 billion years, making the energy map basically “a snapshot of the baby universe,” Shiu says. The WMAP experiment is the successor to NASA’s Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) project, which garnered the 2006 Nobel Prize in physics.

Just as a shadow can give an idea of the shape of an object, the pattern of cosmic energy in the sky can give an indication of the shape of the other six dimensions present, Shiu explains.

To learn how to read telltale signs of the six-dimensional geometry from the cosmic map, they worked backward. Starting with two different types of mathematically simple geometries, called warped throats, they calculated the predicted energy map that would be seen in the universe described by each shape. When they compared the two maps, they found small but significant differences between them.

Their results show that specific patterns of cosmic energy can hold clues to the geometry of the six-dimensional shape — the first type of observable data to demonstrate such promise, says Tye.

Though the current data are not precise enough to compare their findings to our universe, upcoming experiments such as the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite should have the sensitivity to detect subtle variations between different geometries, Shiu says.

“Our results with simple, well-understood shapes give proof of concept that the geometry of hidden dimensions can be deciphered from the pattern of cosmic energy,” he says. “This provides a rare opportunity in which string theory can be tested.”

Technological improvements to capture more detailed cosmic maps should help narrow down the possibilities and may allow scientists to crack the code of the cosmic energy map — and inch closer to identifying the single geometry that fits our universe.

The implications of such a possibility are profound, says Tye. “If this shape can be measured, it would also tell us that string theory is correct.”

The new work was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy and the Research Corp.