New, more effective strategy for producing flu vaccines

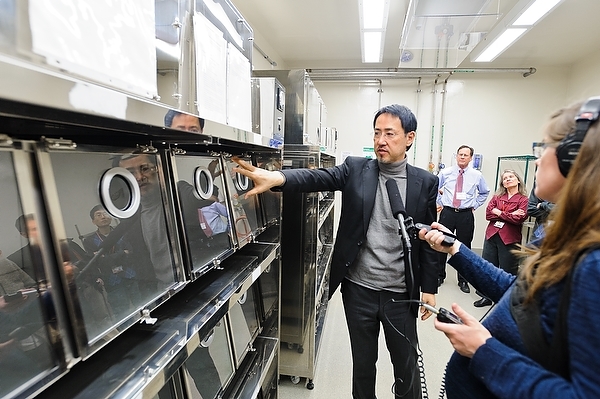

Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a professor of pathobiological sciences in the School of Veterinary Medicine at UW–Madison, talks with a group of media representatives during a tour of the Influenza Research Institute in February 2013. Photo: Bryce Richter

A team of researchers led by Yoshihiro Kawaoka, professor of pathobiological sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, has developed technology that could improve the production of vaccines that protect people from influenza B.

That technology is an influenza B vaccine virus “backbone” that would allow producers to grow vaccine viruses at high yield in mammalian cell culture rather than in eggs. Using the backbone as a template to add vaccine-virus-specific components, it would offer protection against both lineages of influenza B that circulate in the human population.

“We want to provide a system that produces influenza vaccines that are more efficacious,” says Kawaoka. “It is better to produce influenza viruses for vaccine production in cells instead of eggs, but the problem is that influenza virus does not grow well in cell culture compared with embryonated eggs.”

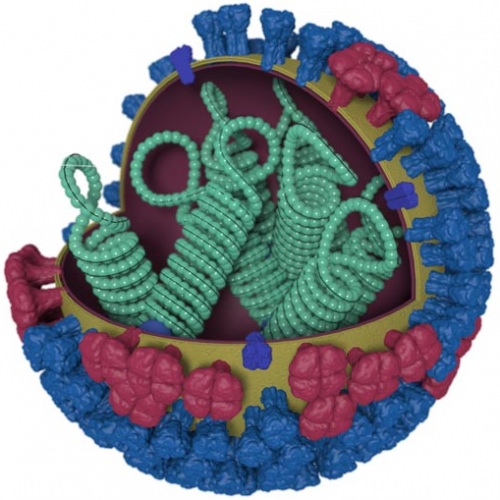

Illustration showing the different features of an influenza virus, including the surface proteins hemagglutinin (blue) and neura-minidase (red). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The new technology may overcome that challenge. The team published its results Monday, Dec. 5, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Each year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, decides which strains of influenza virus to include in the seasonal flu vaccine. It typically includes two influenza A strains and two influenza B strains.

Growing vaccine viruses in high-yield cell culture should improve the ability of seasonal vaccines to protect against influenza A and B because vaccine viruses grown in mammalian cell culture are less likely to mutate compared to those grown in eggs. Mutations can lead to vaccine viruses that no longer match the intended strains of influenza.

“It may still not be perfect, but it will at least be substantially better than current vaccines,” says Kawaoka, who notes no one else has successfully tried to produce high-yield influenza B vaccine virus before now. Last year, his research team created a high-yield influenza A vaccine virus candidate for cell culture production.

Per the CDC, growing vaccine viruses in high-yield cell culture may also enable faster and potentially greater production of vaccine. This could improve the ability of health officials to respond during an influenza pandemic.

To develop the influenza B vaccine virus backbone, Kawaoka’s team screened influenza B viruses for random genetic mutations that led to improved replication.

“It may still not be perfect, but it will at least be substantially better than current vaccines.”

Yoshihiro Kawaoka

Using these mutants as templates, the researchers attached the genes that code for the surface proteins that trigger the human immune response (and thus offer protection in vaccinated individuals) — HA (hemagglutinin) and NA (neuraminidase). They selected the combinations of backbone mutations that supported better growth in cell culture, identifying two candidate backbones that led to higher amounts of vaccine virus.

The team identified the characteristics of each backbone that contributed to their improved yield and also found the backbones to be genetically stable. However, Kawaoka points out that more testing is required to discern whether they would increase vaccine virus yield under industrial conditions.

Several companies and federal agencies have already contacted him about the influenza A and influenza B backbones, Kawaoka says, and he is hopeful the systems can be adopted by vaccine manufacturers and grown in cell culture facilities already available in the United States and Japan.

Several companies and federal agencies have already contacted Kawaoka about the influenza A and influenza B backbones.

Kawaoka’s goal is to help develop more effective vaccines to protect people from influenza infection. According to the CDC, influenza sickens millions, hospitalizes hundreds of thousands, and kills tens of thousands of people each year in the U.S.

“This is something we have to do,” Kawaoka says.

Kawaoka credits the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation for the support to complete this work. “Without that, we couldn’t get it going,” he says.

In addition to WARF, the current study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Center for Research on Influenza Pathogenesis; Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; the Strategic Basic Research Program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency; and the Leading Advanced Projects for Medical Innovation from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development.