New funding to protect bats from fungal epidemic hinges on UW–Madison discoveries

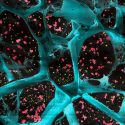

A group of little brown bats show tell-tale signs of white-nose syndrome in a cave in New York. Photo by Al Hicks, New York Department of Environmental Conservation

University of Wisconsin–Madison pediatrician Bruce Klein is trying to save bats.

At first blush, as a physician scientist who is head of pediatric infectious disease at the American Family Children’s Hospital, Klein’s involvement in a continent-wide effort to conserve wildlife species is perhaps a little unexpected. But a fungal disease has devastated several species of hibernating bats, and Klein’s long-term research enterprise centers on understanding how fungi interact with the immune systems of mammals, including both humans and bats.

On March 22, the National Science Foundation and Paul G. Allen Family Foundation announced a grant totaling more than $2 million for the effort to combat that disease, white-nose syndrome. Klein, professor of pediatrics, medicine and medical microbiology and immunology, will lead the project along with Marcos Isidoro Ayza, a graduate student in his lab. The UW–Madison researchers are collaborating with scientists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey and the National Wildlife Health Center in Madison.

Together, they will investigate a multi-pronged approach to protecting wild bats against Pseudogymnoascus destructans, the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome. Klein, Isidoro Ayza and their collaborators plan to test the effectiveness of a drug already approved for humans, both alone and in conjunction with a promising vaccine candidate, as a potential prophylactic against the fungus.

“This is a really nice way to go after a big problem of consequence,” Klein says of the public-private partnership represented in the joint gift from NSF and the Allen Family Foundation. “NSF is interested in basic research, and the Paul Allen Foundation is interested in conservation biology. What a great marriage.”

Bruce Klein

Klein first came to Wisconsin in the early 1980s while working for the CDC as an epidemic intelligence service officer. He began to study blastomycosis, a relatively rare infection caused by inhaling the fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is found in soils and decomposing wood in parts of the Midwest including Wisconsin.

Klein eventually joined the UW faculty and developed a vaccine candidate for blastomycosis. During testing of the vaccine in animals, he identified a particular molecule in the fungus that appeared to spark a protective immune response.

“We did quite a bit of work with this molecule, or antigen, and discovered that it’s highly conserved in the genome of a portion of the fungal kingdom that includes the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome,” says Klein. This suggested the vaccine candidate might also be effective against other fungi, including Pseudogymnoascus destructans.

Indeed, laboratory testing showed that the vaccine candidate for blastomycosis would likely stimulate cellular immunity in bats and potentially protect against the white-nose syndrome fungus. Klein then partnered with scientists at the National Wildlife Health Center and others at UW–Madison, including Global Health Institute Director Jorge Osorio, to develop a vaccine candidate for bat species decimated by the disease.

While the vaccine shows promise, it’s not a silver bullet.

“The best vaccine formulation significantly attenuates the illness in bats,” Klein says. “It doesn’t exert complete protection.”

Such a scenario is surely familiar to the hundreds of millions of Americans who have received vaccinations against COVID-19 over the last couple of years. And similar to how other therapeutics are available to treat Covid, Klein and Isidoro Ayza plan to test an FDA-approved pharmaceutical as a potential supplement or alternative to the white-nose syndrome vaccine.

Marcos Isidoro Ayza

That pharmaceutical is in a class of drugs known as receptor inhibitors, and it has demonstrated promise in Isidoro Ayza’s early laboratory work.

“We are making very fast progress developing these tools,” says Isidoro Ayza, who like Klein came to this work in a bit of a roundabout way.

“My original job was working at a wildlife rescue center to save the lives of injured wildlife,” says Isidoro Ayza, who studied to be a wildlife veterinarian before turning to pathology and eventually basic science as he became more curious about the broader mechanisms and dynamics that drive wildlife diseases.

“I wanted to go deeper in my understanding of the problems,” Isidoro Ayza says. “And white-nose syndrome is one of the most relevant diseases of wildlife. It’s one of the major epidemics of wild animals in recorded history.”

The logistical barriers to vaccinating or treating wild bats are immense, and it will likely take several more years of laboratory and field work to arrive at a realistic strategy for protecting North America’s hibernating bats. At the very least, though, Klein, Isidoro Ayza and their partners hope that the newly funded research will help develop and refine real-world strategies for protecting vulnerable bat populations.

Tags: animal research, disease, research, wildlife