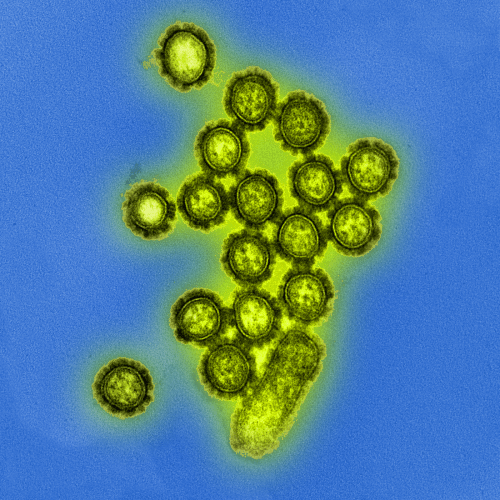

New flu drug drives drug resistance in influenza viruses

On January 31, 2019, an 11-year old boy in Japan went to a medical clinic with a fever. The providers there diagnosed him with influenza, a strain called H3N2, and sent him home with a new medication called baloxavir.

For a few days, he felt better, but on February 5, despite taking the medication, his fever returned. Two days later, his 3-year-old sister also came down with a fever. She, too, was diagnosed with H3N2 influenza on February 8.

An analysis of flu samples collected from her and her brother show she was sickened by a strain of H3N2 harboring a new kind of mutation — one that Yoshihiro Kawaoka, University of Wisconsin–Madison professor of pathobiological sciences, says is resistant to baloxavir, is just as capable of making people sick as the non-mutated version, and is capable of passing from person to person.

Yoshihiro Kawaoka Photo: Jeff Miller

He and colleagues describe this in a study published today [Nov. 25, 2019] in Nature Microbiology that examined the effects of baloxavir treatment on influenza virus samples collected from patients before and after treatment.

“We sequenced the entire viral genome of the 11-year-old boy with drug sensitive influenza virus (before treatment) and the sample from the girl that is drug resistant,” says Kawaoka. “Out of 13,133 nucleotides, there was only one nucleotide difference between the two.”

In other words, what distinguished the virus collected from the brother before treatment and the virus collected from the sister later was a single mutation, a single change in just one letter among the more than 13,000 found in the genetic code of the virus.

“It tells you the virus acquired resistance during treatment and transmitted from brother to sister,” Kawaoka explains.

Baloxavir is part of a new class of antiviral drugs that targets the machinery flu viruses use to copy their genetic material inside their human or animal hosts. It was first licensed in Japan, the United States, and in Hong Kong in 2018 and 2019. In fact, baloxavir represented 40 percent of the market share of influenza drugs in Japan during the 2018–2019 flu season. It will soon be licensed in 20 more countries, Kawaoka says.

However, as he and his co-authors note in the paper, clinical trial data on the drug revealed that some patients infected with either H3N2 or H1N1 influenza who took baloxavir developed a mutation at position 38 of the polymerase acidic protein, part of the virus’s machinery that is targeted by the drug. A previous study by another group showed that the particular mutation had not been described among 17,000 H3N2 virus samples catalogued prior to December 2018.

“The new drug is safe, it went through phase three and was approved safety-wise, but even during clinical trials, the emergence of drug resistance was identified,” Kawaoka explains.

In fact, a previous study in pediatric patients showed the mutation appeared in the samples collected from nearly 1 in 4 of the 77 children enrolled who were also treated with baloxavir.

“Baloxavir-resistant viruses emerge with a relatively high rate in kids” says Kawaoka, also a professor of virology at the University of Tokyo.

Given these findings, Kawaoka and his research team in Japan were interested in understanding the properties of H3N2 and H1N1 viruses — commonly circulating strains that cause illness in people —before and after treatment with baloxavir.

During the 2018–2019 flu season, they set up a system to collect respiratory samples from patients before and after they received the new drug.

For H1N1 influenza, the researchers tested 74 samples from patients before treatment (10 adults and 64 children), and 22 samples from patients both before and after treatment (7 adults and 15 children). There were no instances of mutation in any of the samples before treatment, but there were mutations in one adult and four children after, or in about 23 percent of patients.

For H3N2, the team tested 141 patient samples before treatment (40 adults and 101 children), and two of those from children possessed the mutation. They also studied 16 patient samples before and after treatment (4 adults and 12 children), in which they found no mutations in adult samples but four of the child samples developed the mutation following treatment.

Often, viruses that gain mutations such as drug resistance sacrifice their ability to survive and spread well among their hosts. To understand whether this was true of the baloxavir-driven mutation, the researchers grew the mutant viruses in cell culture and learned it grows just as well as the non-mutated form.

They then tested the mutant H1N1 and H3N2 viruses in hamsters and learned that once the virus mutates, that mutation continues to be copied as new virus grows.

The team also tested the mutated viruses in ferrets and found the mutated form was capable of transmitting from infected animals to healthy ones. The severity of their illness from flu was also similar to the non-mutated form.

While it’s unlikely the mutation will lead to widespread resistance around the world, Kawaoka says it could become a problem among family members in close proximity, and in facilities like hospitals and nursing homes. And, while children seem particularly prone to viral mutation with baloxavir treatment, it appears to occur less frequently in adults. It also quickly reduces the amount of virus in the systems of treated patients. “It’s a good drug for adults,” Kawaoka says.

And, he explains, patients with H1N1 or H3N2 that do develop resistance to baloxavir with treatment still do respond to other virus-fighting drugs.

“The drug resistant virus does transmit but there are so many influenza viruses worldwide and only a small population will be treated with this drug,” Kawaoka says. “The vast majority remain drug sensitive.”

The study was funded by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP18am001007, JP19fm0108006, JP19fk0108031, JP19fk0108056, JP19fk0108058 and JP19fk0108066); the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology of Japan (16H06429, 16K21723 and 16H06434); and the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (HHSN27220140008C).

Author Makoto Yamashita has received a speaker’s honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Pharmaceutical. Yoshihiro Kawaoka has received a speaker’s honoraria from Toyama Chemical and Astellas, and grant support from Daiichi Sankyo Pharmaceutical, Toyama Chemical, Shionogi and Co., and Kyoritsu Seiyaku. Kawaoka is also founder of FluGen.