Model virus structure shows why there’s no cure for common cold

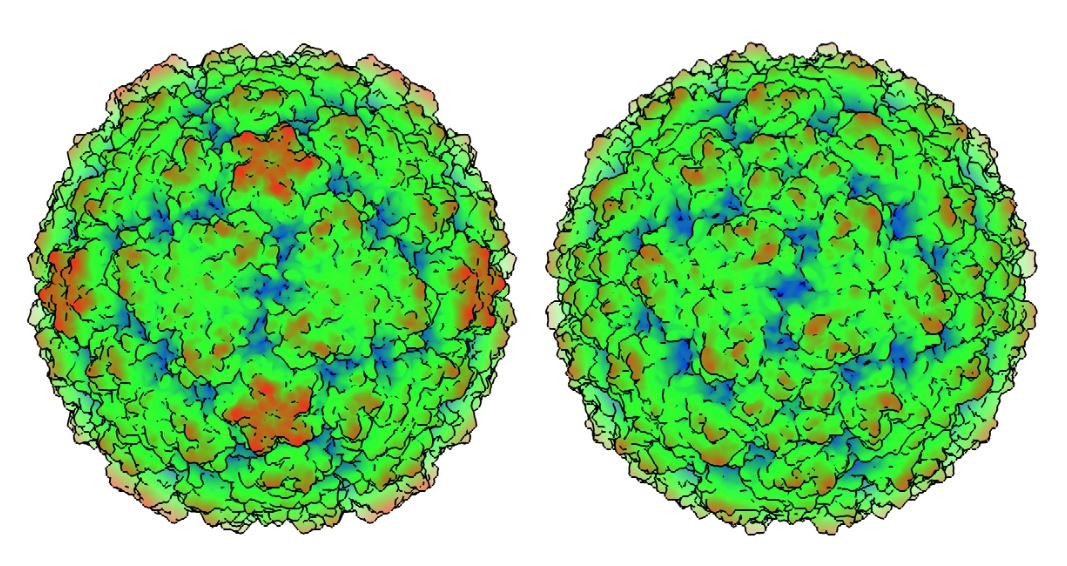

Two faces of the common cold. The protein coat of the “missing link” cold virus, Rhinovirus C (right), has significant differences from the more observable and better studied Rhinovirus A. Those differences explain why no effective drugs have yet been devised to thwart the common cold.

In a pair of landmark studies that exploit the genetic sequencing of the “missing link” cold virus, rhinovirus C, scientists at UW–Madison have constructed a three-dimensional model of the pathogen that shows why there is no cure yet for the common cold.

Writing today (Oct. 28, 2013) in the journal Virology, a team led by UW–Madison biochemistry Professor Ann Palmenberg provides a meticulous topographical model of the capsid or protein shell of a cold virus that until 2006 was unknown to science.

Rhinovirus C is believed to be responsible for up to half of all childhood colds, and is a serious complicating factor for respiratory conditions such as asthma. Together with rhinoviruses A and B, the recently discovered virus is responsible for millions of illnesses yearly at an estimated annual cost of more than $40 billion in the United States alone.

Ann Palmenberg

The work is important because it sculpts a highly detailed structural model of the virus, showing that the protein shell of the virus is distinct from those of other strains of cold viruses.

“The question we sought to answer was how is it different and what can we do about it? We found it is indeed quite different,” says Palmenberg, noting that the new structure “explains most of the previous failures of drug trials against rhinovirus.”

The A and B families of cold virus, including their three-dimensional structures, have long been known to science as they can easily be grown and studied in the lab. Rhinovirus C, on the other hand, resists culturing and escaped notice entirely until 2006 when “gene chips” and advanced gene sequencing revealed the virus had long been lurking in human cells alongside the more observable A and B virus strains.

The new cold virus model was built “in silico,” drawing on advanced bioinformatics and the genetic sequences of 500 rhinovirus C genomes, which provided the three-dimensional coordinates of the viral capsid.

The lack of a three-dimensional structure for rhinovirus C meant that the pharmaceutical companies designing cold-thwarting drugs were flying blind.

“It’s a very high-resolution model,” notes Palmenberg, whose group along with a team from the University of Maryland was the first to map the genomes for all known common cold virus strains in 2009. “We can see that it fits the data.”

With a structure in hand, the likelihood that drugs can be designed to effectively thwart colds may be in the offing. Drugs that work well against the A and B strains of cold virus have been developed and advanced to clinical trials. However, their efficacy was blunted because they were built to take advantage of the surface features of the better known strains, whose structures were resolved years ago through X-ray crystallography, a well-established technique for obtaining the structures of critical molecules.

Because all three cold virus strains all contribute to the common cold, drug candidates failed as the surface features that permit rhinovirus C to dock with host cells and evade the immune system were unknown and different from those of rhinovirus A and B.

Based on the new structure, “we predict you’ll have to make a C-specific drug,” explains Holly A. Basta, the lead author of the study and a graduate student working with Palmenberg in the UW–Madison Institute for Molecular Virology. “All the [existing] drugs we tested did not work.”

With a structure in hand, the likelihood that drugs can be designed to effectively thwart colds may be in the offing.

Antiviral drugs work by attaching to and modifying surface features of the virus. To be effective, a drug, like the right piece of a jigsaw puzzle, must fit and lock into the virus. The lack of a three-dimensional structure for rhinovirus C meant that the pharmaceutical companies designing cold-thwarting drugs were flying blind.

“It has a different receptor and a different receptor-binding platform,” Palmenberg explains. “Because it’s different, we have to go after it in a different way.”

In addition to Basta and Palmenberg, co-authors of the new studies include Jean-Yves Sgro, Shamaila Ashraf, Yury Bochkov and James E. Gern, all of UW–Madison.

Tags: biosciences, drugs