Mildred Fish-Harnack honored as hero of resistance to Nazi regime

“Ich habe Deutschland auch so geliebt”

“And I have loved Germany so much.”

Those were the last words of Mildred Fish-Harnack before the blade of the guillotine fell.

She was sentenced to six years of hard labor for the crimes of treason and espionage but that wasn’t enough for Adolf Hitler. Fish-Harnack became the only American civilian to be executed on the direct order of Hitler.

Her story has gotten somewhat lost in the vast horrors of the Third Reich. The punishment continued long after her death. In the Cold War years after World War II, Fish-Harnack’s name and legacy were not honored in the U.S., because she and her husband were believed to have been connected with Communism. But the smearing of her name and the burying of her story has become part of why she’s being recognized today.

“Mildred,” a sculpture by John Durbrow, was dedicated by the city of Madison in her honor July 12 in Marshall Park, 2101 Allen Boulevard in Madison. The black granite obelisk was designed by John Durbrow, a longtime Manitowoc-area resident and retired professor of architecture at Chicago’s Illinois Institute of Technology. The statue was originally placed Oct. 31, 2018 by the city of Madison Arts Commission. The dedication was attended by an academic delegation of representatives from eight German universities. A similar sculpture is planned for the campus of the University of Giessen, where she completed a PhD in literature.

The sculpture “Mildred”, dedicated to Mildred Fish-Harnack in Marshall Park, with Picnic Point in the background. Picnic Point is where she was engaged to her husband, Arvid.

The academic delegation from Hessen, Germany, along with Interim Provost Jim Henderson, International Division Vice Provost and Dean Guido Podestá, International Division Associate Dean Rick Keller, ID Director of External Relations Maj Fischer, and artist John Durbrow. Photos by Steve Barcus

How does a woman from Wisconsin end up a celebrated hero of resistance to the Nazi regime in Germany?

A bit of chance is involved, along with her strong sense of what is right and wrong.

‘Mili’

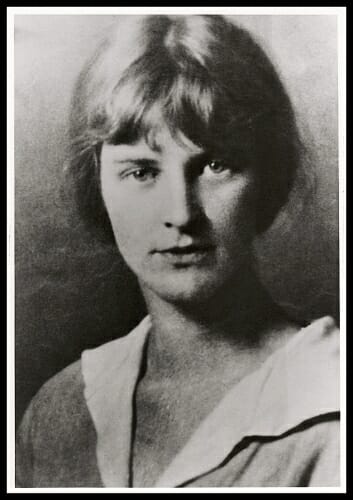

Mildred Elizabeth Fish was born in Milwaukee Sept. 16, 1902. She was one of four children born to William C. and Georgina Fish. She grew up on the west side of Milwaukee, close to “Sauerkraut Boulevard.” Although she wasn’t German, Mildred learned how to read, write, and speak both German and English. Known as “Mili” to her friends, she attended West Division High School, now known as the Milwaukee High School of the Arts.

Following the death of her father, the family moved to Chevy Chase, Maryland. Mildred attended Western High School her senior year. She managed to pack a lot in one year, playing on both the basketball and baseball teams, serving as editor for the Trailblazer, and playing the role of Princess Angelica in William Makepeace Thackeray’s “The Rose and the Ring,” the senior class play. Following her graduation in 1919, she attended George Washington University for two years. With money from her savings and from her family, she returned to her home state to attend UW–Madison.

A chance meeting

Mildred dreamt of becoming a writer and joined the Wisconsin Literary Magazine.

Ruth Wallerstein, an assistant professor of English, described Mildred as “quite distinguished as a poet.” Warner Taylor, chairman of the English department, described her as “very aesthetic and a little on the radical side.”

(Samples of her writing while at UW–Madison can be seen here and here.)

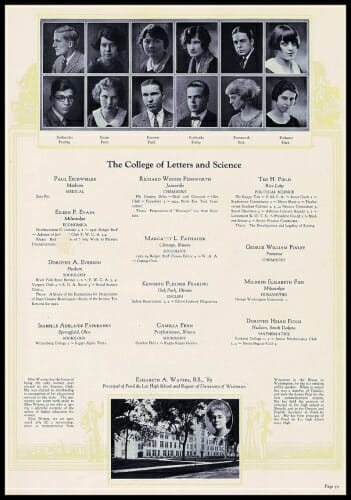

Mildred graduated in 1925 with her bachelor’s degree and stayed at the university to teach English and attend graduate school. She received her master’s in 1926.

In 2011, “Wisconsin’s Nazi Resistance: The Mildred Fish-Harnack story,” aired on Wisconsin Public Television. At long last, her story was being shared, this time using recently uncovered information, including official German documents and papers from U.S.

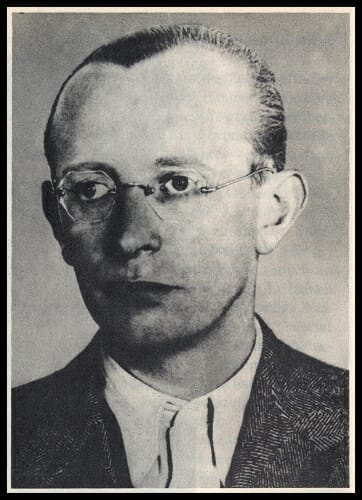

Arvid Harnack, a Rockefeller Scholar from Germany, came from a family of academics. He was on fellowship while attending UW–Madison and was working on getting his second doctorate. Arvid met Mildred when he went to the wrong building and ended up in her class. Or at least that’s how the story goes.

“He saw this radiant teacher with this blonde hair. Everyone says that Mildred was the most beautiful girl on the university campus. She was absolutely gorgeous,” says Shareen Blair Brysac, author of “Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra,” in the documentary. “He went up and introduced himself. He apologized for his faltering English, and she apologized that she didn’t speak German very well. And he proposed he study English with her and she study German with him. And that was the beginning of the romance.”

Arvid was in love.

“I still remember how a letter arrived for my mother with the laconic sentence, ‘I’ve met a girl with the beautiful name, Mildred,’ Arvid’s sister Inge writes in her memoirs. “My mother read it and said with assertiveness, ‘That’s her.’ Meaning, that will be his wife.”

Arvid wrote often to his mother, Clara Harnack, back in Germany about life in Madison.

“Spent a day of brilliant sunshine on Lake Mendota. Lots of flowers under the green trees and exotic, wonderful birds. On another Sunday we went to Devil’s Lake. It’s a crystal clear lake between two high cliffs. We layed (laid) down on the highest point and looked down and across the wide countryside. The cliffs here are an exception the rest of Wisconsin is fairly level and flat. I read Faust with Mildred. Mildred seems to have a feel for languages because she learned enough Greek writing a few months to be able to read Homer fairly quickly.”

June 8, 1926: “I am very happy. I’ve got engaged. The whole thing is actually very curious because I can hardly speak English and Mildred knows no German. I made up my mind when I saw her for the second time. We got engaged yesterday.”

Aug. 8, 1926: “Mildred and I were married yesterday. Mildred passed her Master’s degree exam 2 days before. She is now a Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts. We celebrated the wedding on her brother’s farm. A large part of the Fish family was gathered there.

Mildred’s mother is simple and yet very fine. We arrived at the farm at 5p and Mildred and I left again at 9p We were married on the farm by Father Johnston (Methodist Episcopal Church) He made it short and painless.”

The bride hyphenated her name, a bold move at that time, becoming Mildred Fish-Harnack.

The arrest

They moved to Germany, where Mildred worked on her doctorate while Arvid worked for the German government. Mildred taught modern American literature at Berlin University, becoming one of the first Americans on a faculty that included Albert Einstein. The position was short lived, according to a story in The New York Times. Fifteen months later, the university had fired her for not being “Nazi enough.”

Alarmed by the rise of Hitler and the Nazi regime, Mildred and her husband joined a small resistance group. Their group published an underground newsletter, and fed economic information to the U.S. and Soviet embassies in Berlin. After Germany invaded Russia, the group transmitted military intelligence to Moscow via radio “concerts,” prompting the Gestapo to call them the “Red Orchestra.”

The group was discovered and arrested in September of 1942.

Mildred was taken to Charlottenburg Women’s Prison. Meticulous records kept by the Nazis details what assets Mildred had at the time of her arrest:

- $8.47 in my pocket, she estimated.

- 1 contract ticket United States Lines $127 in her purse.

- Some money in Deutsche Bank

- Apartment furnishings, especially in the two front rooms, with two Oriental carpets; a light and a dark one with uneven stars and color

Arvid was sentenced to death for high treason and espionage. He was executed in December of 1942, hung using a foot-long rope. It was a method Nazis refined to prolong the victim’s agony.

“It can be assumed that I am widowed,” Mildred said. “I haven’t however received an official letter informing me of the death of my husband, who was supposed to be executed.”

Arvid died believing that Mildred would serve her prison sentence, not knowing she’d face the guillotine. But as he faced certain death, he thought of their time in Madison, writing this letter to Mildred.

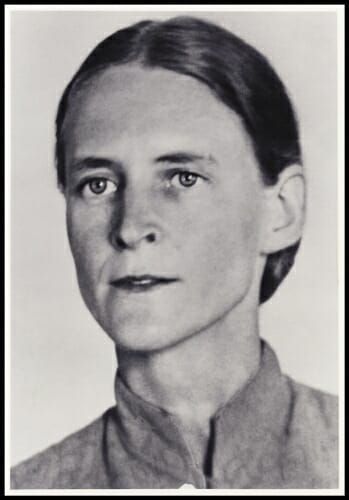

Mildred Fish-Harnack in prison, 1943. Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand Material. Copy courtesy of Arthur Heitzer

“Can you remember Picnic Point, when we got engaged?…And before that our first serious talk at lunch in a restaurant in State Street? That talk became my guiding star and has remained so.” He ends with the following: “You are in my heart…My greatest wish is that you are happy when you think of me. I am when I think of you. Many, many kisses! I hug you tight. Your A.”

He also wrote a letter to his family.

When Mildred’s new trial came, her family was warned by the prosecutor, “I urgently warn the Harnack family not to undertake anything whatsoever in favor of this woman. She no longer belongs to your family.”

At 6:57 p.m. Feb. 16, 1943, she was strapped to a bench and guillotined. The Nazis noted it took Mildred seven seconds to die.

Mildred’s story finally told

The CIA investigated surviving members of the resistance as Communist spies. Mildred’s name and story were mostly forgotten. In 1947, UW–Madison recognized Mildred in its Alumni Magazine.

“But as the Cold War heated up, a move to honor Mildred was halted, because her pro-Communist sympathies could not be ruled out,” according to the WPT documentary. “Wisconsin senator Joe McCarthy and his hunt for Communists may have been a factor. So instead of honoring Mildred, the university’s inquiry triggered an FBI investigation.”

Mildred and Arvid were written off as communists.

Gradually, the true story emerged as documents and family members fought to clear their names.

In 1986, Mildred Fish-Harnack Day was established in Wisconsin. It takes place every year on her birthday, Sept. 16th.

Want to learn more? View this Wisconsin Public Television documentary about Mildred Fish-Harnack

Mildred’s life and legacy is recognized at the University of Wisconsin–Madison through the Mildred Fish-Harnack Human Rights and Democracy Lecture, an event held each academic year to promote greater understanding of human rights and democracy, and enrich international studies.

The recently released “Resistance Women,” by Jennifer Chiaverini, New York Times bestselling author of “Mrs. Lincoln’s Dressmaker,” is inspired by Mildred’s story .

The Madison sculpture honors the strength, courage, and resolve to address early on the forces of oppression which eventually inflamed the entire world, Durbrow says in his artist statement.

“The memorial is intended to spiritually unite Mildred with her formative base and intellectual center, Wisconsin.”

In 2013, supporters gathered in Berlin to honor her.

“She couldn’t turn her back on Germany,” said Jilly Allenby-Ryan, the grandchild of Mr. Harnack’s sister. She was reading aloud from a letter her grandmother had written to remember Ms. Fish-Harnack after her death, The New York Times reported. “She wasn’t without fear, but she was brave,” Ms. Allenby-Ryan continued.

At one point during the afternoon, Neela Härting, 79, pulled out a wrinkled piece of paper to show to Ms. Allenby-Ryan, her cousin. It was a photocopy of a black-and-white picture of a 25-year-old Mr. Harnack dated Sept. 20, 1925.

“They would not want to be remembered as heroes or victims,” Ms. Allenby-Ryan would later say. “But as people.”

It’d be easy to think that this young woman from Wisconsin didn’t know what she was getting into. Perhaps she was just following her husband. But this was a woman who hyphenated her last name in 1926. She’d been warned of the dangers and told to come back to safety in the United States.

“Well it’s not a question of how dangerous it is, I’ve got work to do, I’m not going,” she said.

She was only 40 when she died but the months in prison had taken its toll. Her blonde hair had turned white, the prison chaplain described. Starved and broken, she could no longer stand.

In those last moments, the chaplain brought Mildred an orange along with a picture of her mother. Eyes filled with tears, she kissed the photo again and again. On the back, she wrote: “The face of my mother expresses everything I want to say at this moment. This face was with me all through these last months.”

Tags: history, Jewish studies