Madison company obtains FDA approval for sleep-data software

EnsoData CEO and co-founder Chris Fernandez is one of EnsoData’s three code wizards. All three EnsoData employees have an intensive background in handling big data. David Tenenbaum

EnsoData, a UW–Madison spinoff that sifts through mountains of data from studies at sleep centers, received approval from the Food and Drug Administration on April 11 for its automated sleep analysis product.

“FDA clearance of the EnsoSleep technology represents a historic milestone for our company and sleep clinicians who want to realize the huge time savings that are possible with automated analysis of sleep study results,” said Chris Fernandez, EnsoData’s CEO and co-founder.

“It took months of detailed testing and validation of our product by everyone on the EnsoData team, along with our early clinical partners,” Fernandez said.

Nick Glattard works on a desk resting on drums; home-made music provides stress relief amid long sessions of writing computer code. David Tenenbaum

Fernandez graduated from UW–Madison in 2015 with a master’s in biomedical engineering.

“Each sleep study can produce a gigabyte of data,” says Fernandez, “and that presents an opportunity to reduce costs and perhaps increase accuracy.”

EnsoData’s software replicates the analyses that sleep doctors perform, but at the speed of computers.

“Imagine you are a sleep specialist with a 20-bed practice,” Fernandez says. “Every night, every patient wears between four and 20 sensors for six to eight hours. So in the morning, you need to comb through potentially 160 hours of not necessarily the most exciting data, and identify every instance of stopped breathing, or significant changes in the sleep cycle, blood oxygen, or heart rhythm.”

Most doctors, Fernandez says, still evaluate data by hand, which “can take an hour per patient. It’s complex and boring at the same time,” and different raters often disagree when interpreting the same study.

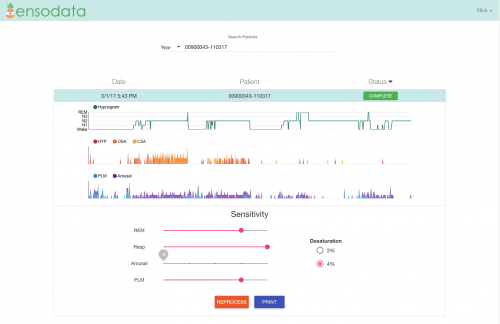

Ensodata has software designed to automate the interpretation of this kind of data. This picture shows the EnsoSleep clinical dashboard, with summary-level analytics on stage of sleep (Rapid eye movement, wake, etc.), respiratory events including apneas and hypopneas, arousals and leg movements. Courtesy Ensodata Inc.

The problem is huge, Fernandez says. “The American Institute of Sleep Medicine says 50 to 70 million people have a sleep disorder.” Twenty-nine million alone have apnea, a periodic halt in breathing that, though largely undiagnosed, “doubles medical expenses over time and leads to significant complications, including stroke, heart problems and depression,” Fernandez says.

Last April, EnsoData raised $550,000 in seed money, much of which was used to pay consultants for the critical FDA application.

In a light, airy office in a historic building a block from the state capitol in Madison, Fernandez, co-founder Sam Rusk, and Nick Glattard continue refining their software, trying to increase accuracy and reduce work for users. “We want to pull the data out, analyze it and put it back into the sleep-lab software,” Fernandez says. “Our goal is to make the transfers seamless, with no extra clicks, and to be the most affordable and reliable option.”

As Fernandez envisions it, all the studies would be analyzed accurately before the doctor arrives at the sleep center in the morning. “Our goal is that the doctor can view results and consult with the patient that same day. This should allow them to spend more time on education.”

Most sleep labs have a waiting list of three months or more, Fernandez says. “If we can speed the analysis, that should make an immediate impact on the backlog.”

Ironically, as Fernandez and his two collaborators eye a breakthrough into commercial acceptance, some of the credit goes to one success, and one bit of good-bad luck. Shortly after they entered UW–Madison, Fernandez and Glattard started a custom apparel company. “As sophomores, we made $68,000 revenue selling T-shirts around UW–Madison,” Fernandez says. “But we were studying biomedical engineering and thought that maybe we should focus on that, not shirts.”

The opportunity, and the good-bad luck, came in a biomedical engineering class aimed at producing a real world solution to a real problem.

Every one of the problems that Fernandez preferred was taken before his choice came, so he was stuck with one that the professor, Willis Tompkins, described as the hardest: a wireless device to measure blood oxygenation. The device had obvious uses for home monitoring of chronic diseases, and Fernandez and other UW–Madison students worked on it for three years. Yet despite doing well in several business competitions, they could not raise enough money.

EnsoData co-founder Sam Rusk in the company’s offices on State Street near the state Capitol.

Still, losing “was a milestone psychologically,” Fernandez says. “People were taking us seriously, so we should keep at this.”

Fernandez says he and Rusk, “went back to the drawing board,” in a disciplined search for another problem. In summer, 2014, “In a class with some undergraduate business majors, we interviewed about 100 UW–Madison people involved in health in various ways. We said, ‘We know machine learning, big data, and love health care. Do you have anything to work within this trifecta?’

Ruth Benca, who was then chair of sleep medicine at UW–Madison, pointed to the data-analysis problem in sleep medicine. “She told us, ‘If you could solve it, we could use it today.’”

The FDA approval means that EnsoData’s system is “substantially equivalent” to currently available methods – meaning analysis by hand, Fernandez says.

“Our primary objective is to get the technology into the hands of as many clinicians as possible, to assist them in scaling up their sleep testing capabilities and patient access. We are focused on working closely with our customers to maximize the time and cost savings they derive from EnsoSleep and their improved clinical workflow.”

Fernandez, a native of Aurora, Illinois, says his father fled the chaos in Bangladesh in 1981. Starting his own business, he says, reflected “a strong desire to be financially independent.”

Although the company’s “secret sauce” is confidential, Fernandez says “we are trying to get the computer to emulate human visual-pattern recognition and perceptual reasoning, using quantitative rules, recommendations and procedures from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.”

Accomplishing the automated analyses rests on expertise acquired at UW–Madison, says Fernandez. “Nick and I took every class in machine learning and pattern recognition that the university has to offer.”

Both Glattard and Fernandez have master’s in biomedical engineering from UW–Madison; Rusk has a bachelor’s in electrical and computer engineering from UW–Madison.

Ironically, being a student, “Was the best time to start a business,” Fernandez says. “People don’t expect you to have everything figured out, so you have permission to fail. And it allowed us connect with amazing people for advice and mentorship.”

Even though he took pre-med courses at UW–Madison before switching to engineering, Fernandez says the goal is largely the same. “Doctors treat one patient at a time, and that’s absolutely critical. But I realized I could use technology to work with a million patients at the same time.”

Tags: data, engineering, spinoffs