Lung cell found to act as sensor, regulator of immune response

An uncommon and little-studied type of cell in the lungs has been found to act like a sensor, linking the pulmonary and central nervous systems to regulate immune response in reaction to environmental cues.

The cells, known as pulmonary neuroendocrine cells or PNECs, are implicated in a wide range of human lung diseases, including asthma, pulmonary hypertension, cystic fibrosis and sudden infant death syndrome, among others.

Until now, their function in a live animal was unknown. A team led by University of Wisconsin–Madison medical geneticist Xin Sun reports in the current (Jan. 7) issue of the journal Science that PNECs are effective sensors seeded in the airway of many animals, including humans.

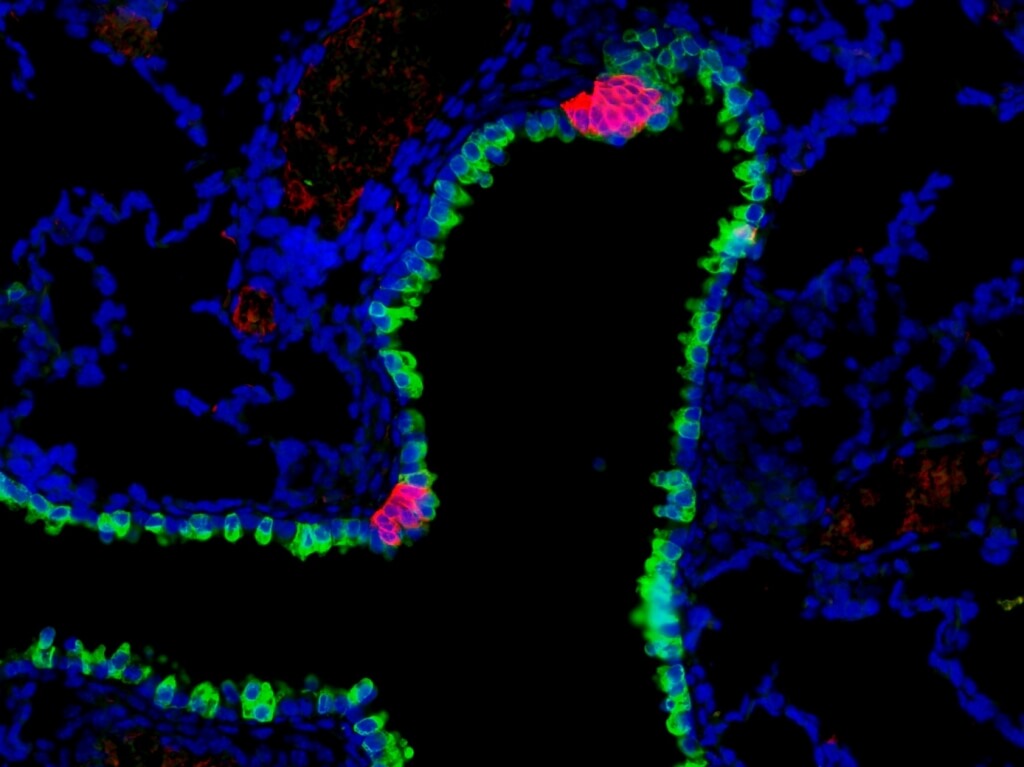

Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells (red) are rare cells found in clusters along the mammalian airway, where they act as sensors, sending information to the central nervous system. These clusters are found interspersed among other airway epithelial cells (green). Leah Nantie

“These cells make up less than one percent of the cells in the airway epithelium,” the layer of cells that lines the respiratory tract, explains Sun. “Our conclusion is that they are capable of receiving, interpreting and responding to environmental stimuli such as allergens or chemicals mixed with the air we breathe.”

Discovering the function of the cells may provide new therapeutic avenues for a wide range of serious diseases of the pulmonary system.

Sun and her group initially set out to find the underlying cause of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), a fairly common birth defect where a hole in a newborn’s diaphragm, the muscle that controls breathing, lets organs from the abdomen slip into the chest. The deformed diaphragm can be repaired surgically, but many of the babies still die. Those that survive can have symptoms similar to asthma or pulmonary hypertension.

The Wisconsin group homed in on a pair of genes known as ROBO1 and ROBO2. Mutations in the genes had previously been implicated in CDH. By knocking out ROBO genes in mice, Sun and her colleagues were able to mimic CDH. Unexpectedly, they also discovered that PNECs were disorganized in the ROBO mutants. In a healthy mouse, PNECs mostly form clusters of cells. “In the mutant, they don’t cluster,” says Sun. “They stay as solitary cells, and as single cells they are much more sensitive to the environment.”

The team went on to show that defects in the PNECs caused the hyperactive immune response in the ROBO mutant lungs.

PNECs are the only known cells in the airway lining that are linked to the nervous system. It seems, explains Sun, that they are basically distributed sensors, gathering information from the air and relaying it to the brain. Interestingly, the same cells also receive processed signals back from the brain to amp up their secretion of neuropeptides, which are small protein molecules that are potent regulators of the immune response.

Disorders of the immune system like asthma are associated with increased expression of neuropeptides. Showing that PNECs play a role in regulating host response through the release of neuropeptides suggests that it may be possible to devise ways of regulating them to prevent or ameliorate disease, Sun says.

Sun is a professor of medical genetics in the Laboratory of Genetics of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health. Contributing to the work were Kelsey Branchfield, Leah Nantie, Jamie Verheyden, Pengfei Sui and Mark Wienhold, all of UW–Madison. The new study was supported by awards from the American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health and, at the campus level, by the Wisconsin Partnership Program and a Romnes Faculty Fellowship. Romnes Fellowships are awarded by the UW–Madison Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.