Instructors adapt hands-on labs to hands-off times

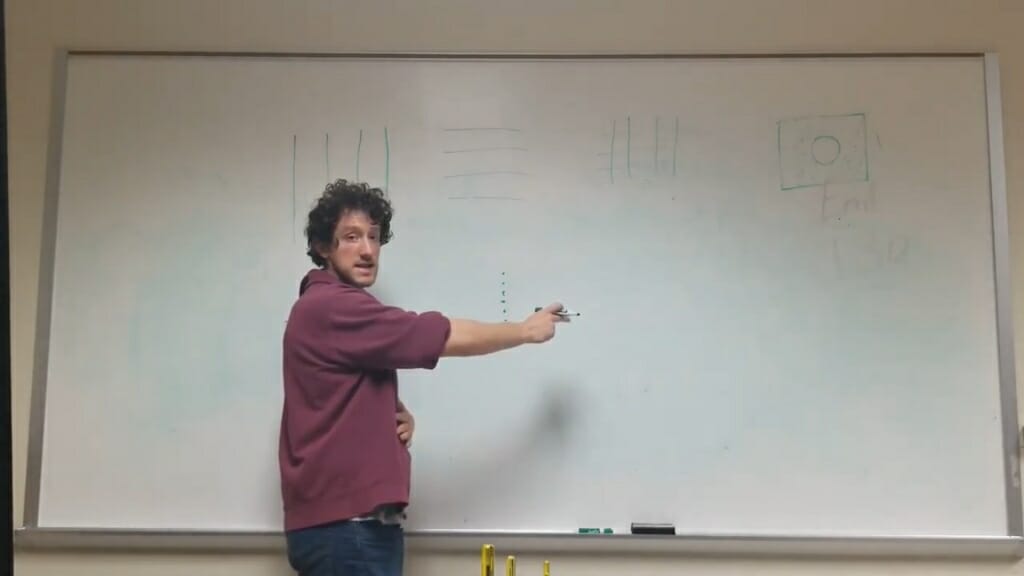

Physics 325 TA Zach Bucholtz writes on the board during an online walkthrough of an optics lab. Submitted photo

For many undergraduate students, laboratory classes already prove difficult in-person. But during the COVID-19 crisis, laboratory instructors face a new challenge: translating material meant to be taught hands-on into an online format, and then teaching it to students spread across the country.

Ever since the University of Wisconsin–Madison announced the suspension of in-person instruction, faculty teaching science classes with lab components have scrambled to substitute hands-on, in-person labs with online videos or activities.

General Chemistry Laboratory Director Chad Wilkinson and his team had to figure out a way to provide online lab instruction for the thousands of early-career STEM majors taking general chemistry.

To move labs online, Wilkinson said his team started using software platforms to help students make observations, and they’ve created example data sets for students to analyze, since they can’t collect their own data.

Wilkinson said students had already used some of the online tools, like the modeling software WebMO, in previous labs, so teaching students the software wasn’t too difficult. But not every student or instructor has access to the same technologies, hardware, or connectivity, so finding the right platforms to fit everyone’s needs also proved a challenge.

Wilkinson also said students inevitably miss out on some of the important hands-on experiences they’d get being in the lab space during in-person instruction.

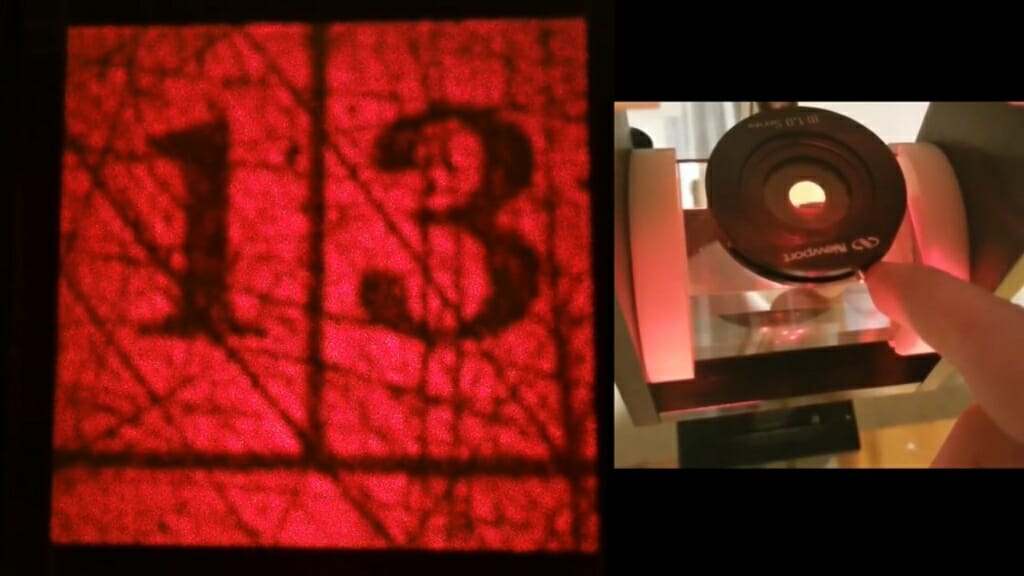

A Fourier transform revealed from an imaging system in the video walkthrough of Yavuz’s online optics lab. Submitted photo

“The most difficult impact is the loss of uniquely in-lab experiences for students, particularly where technique is concerned,” Wilkinson said. “You can lecture until you are blue in the face about titrations, but for many students it just isn’t going to click until they’re standing in front of a burette actually performing a titration.”

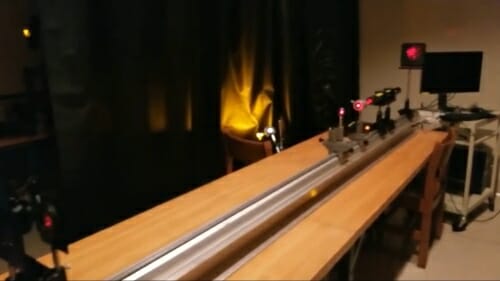

Jim Reardon, director of instructional labs for the Physics Department, said physics instructors have played around with several strategies, including filming the labs and showing students the videos, replacing the labs with online simulations, replacing the lab with a report or project and, in one case, sending students the lab apparatus so they can complete the lab at home.

In some cases, Reardon said physics instructors have been able to keep the content exactly the same as if the labs would be in-person — but instructors who replaced labs with simulations or written reports had to sacrifice some of their original lab content.

Physics Professor Deniz Yavuz teaches Phys 325 Optics, an upper-level class with a lab component. Yavuz cited some of the same challenges as the chemistry department — certain things just cannot be taught without an in-person instructor.

“It is really an experimental science — physics, and optics also,” Yavuz said. “So it is really helpful for the students to do [the experiments] with their hands.”

Yavuz said at first, he and his TAs recorded the labs, so students could watch the procedure, take notes and ask questions. But after campus shut down, they couldn’t gain access to Chamberlain Hall, where all the lab materials were. This change forced them to adapt — instead of making videos, Yavuz assigned research projects, so students could explore the material independently.

Generally, the students adjusted well to this change, too, Yavuz said, but since research projects require more independence and self-motivation than just watching a guided lab, a few of his students have struggled to stay organized.

Because Yavuz only has 46 students, it’s easier for him to keep in contact with everyone, and help whoever is struggling, than it would be for Wilkinson with all the general chemistry sections. Yavuz said he’s noticed his students living alone tend to face more stressors, but otherwise, he said most of his students have adapted to the changes.

Wilkinson said chemistry students also seem to have adjusted well. He said his team has worked hard in the background to make the change as seamless as possible, learned a lot throughout the process, and will continue to look for more ways to better serve students.

Reardon said while challenging, the situation also came with some silver linings. The students in physics classes that showed videos of the lab procedure got to see the lab as it should work perfectly, minimizing experimental errors they might get doing the lab themselves.

“Some of the physical phenomena studied in the labs are much more apparent with the use of good than otherwise experimental technique,” Reardon said. “These can be exhibited in video so that everyone, not just lab groups with good technique, can see them.”

Reardon said since all the students start with the same data, and that data includes uncertainties in measurement, it is much easier for TAs to give feedback on the correct propagation of those uncertainties.

Yavuz said overall, he’ll be happy when in-person instruction resumes and students can get back into physical labs. But through the process, he’s learned it’s not a bad idea to have recorded videos of the labs as a backup plan.

“It is really important to be physically there, and doing the experiments, and taking data,” Yavuz said. “That experience is not there anymore. I think [the students] will be missing out on stuff. But I’m hoping things will go back to normal.”