Human stem cell-derived heart cells are safe in monkeys, could treat congenital heart disease

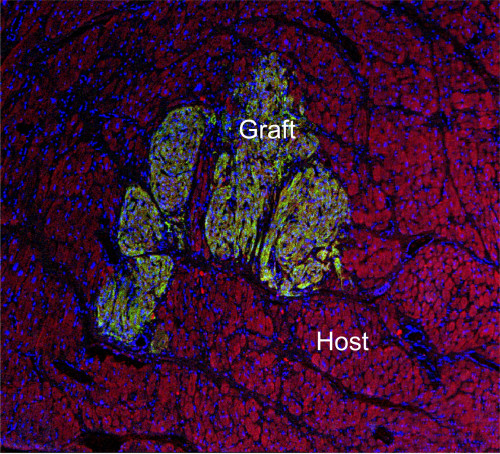

Heart muscle cells grown from human induced pluripotent stem cells (in green) have successfully integrated into rhesus macaque heart muscle in this microscope image of heart tissue from a new study by UW–Madison and Mayo Clinic researchers. Photo courtesy Emborg Lab / UW–Madison

Heart muscle cells grown from stem cells show promise in monkeys with a heart problem that typically results from a heart defect sometimes present at birth in humans, according to new research from the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Mayo Clinic.

Heart disease, the No. 1 killer of Americans, can affect people at any time across their lifespans — even from birth, when heart conditions are known as congenital heart defects. Regenerating tissue to support healthy heart function could keep many of those hearts beating stronger and longer, and this is where stem cell research is stepping in.

A research team led by Marina Emborg, professor of medical physics in the UW–Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, and Timothy Nelson, physician scientist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, reported recently in the journal Cell Transplantation that heart muscle cells grown from induced pluripotent stem cells can integrate into the hearts of monkeys with a state of pressure overload.

Also referred to as right ventricular dysfunction, pressure overload often affects children with congenital heart defects. Patients experience chest discomfort, breathlessness, palpitations and body swelling, and can develop a weakened heart. The condition can be fatal if left untreated.

Nearly all single ventricle congenital heart defects, particularly those in the right ventricle, eventually lead to heart failure. Surgery to correct the defect is a temporary solution, according to the researchers. Eventually, patients may require a heart transplant. However, the availability of donor hearts — complicated by the young age at which most patients require a transplant — is extremely limited.

In their new study, the researchers focused on grafts of stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as a possible complementary treatment to traditional surgical repair of cardiac defects. Their goal was to directly support ventricular function and overall healing.

“There is a great need for alternative treatments of this condition,” says Jodi Scholz, the study’s lead author and chair of Comparative Medicine at Mayo Clinic. “Stem cell treatments could someday delay or even prevent the need for heart transplants.”

The researchers transplanted clinical-grade human induced pluripotent stem cells — cells collected from human donors, coaxed back into a stem cell state and then developed into cell types compatible with heart muscle — into rhesus macaque monkeys with surgically induced right ventricular pressure overload. The cells successfully integrated into the organization of the surrounding host myocardium, the muscular layer of the heart. The animals’ hearts and overall health were closely monitored throughout the process. The authors noted that episodes of ventricular tachycardia (an increased heart rate) occurred in five out of 16 animals receiving transplanted cells, with two monkeys presenting incessant tachycardia. These episodes resolved within 19 days.

“We delivered the cells to support existing cardiac tissue,” Emborg says. “Our goal with this particular study, as a precursor to human studies, was to make sure that the transplanted cells were safe and would successfully integrate with the organization of the surrounding tissue. We leveraged my team’s experience with stem cells and cardiac evaluation in Parkinson’s disease to assess this innovative therapeutic approach.”

The research proved the feasibility and safety of using stem cells in the first nonhuman primate model of right ventricular pressure overload. Macaques, in particular, have been critical to advancing stem cell therapies for heart disease, kidney disease, Parkinson’s disease, eye diseases and more.

“The demonstration of successful integration and maturation of the cells into a compromised heart is a promising step towards the clinical application for congenital heart defects,” Emborg says.

The research was supported by the Todd and Karen Wanek Family Program for Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome and National Institutes of Health Grant P51OD011106 to the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center.

Tags: animal research