Photo gallery Hardy scientists launch weather balloon in bitter cold

Professor of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Grant Petty and a group of students launched a helium-filled weather balloon from frozen Lake Mendota at sunrise on Jan. 31, with the temperature at around minus 24-degrees Fahrenheit. The balloon is carrying a meteorological instrument, called a radiosonde, which could reach up to 20 miles above Earth’s surface. The device takes readings of temperature and humidity and helps Petty determine the location of the boundary between two atmospheric layers: the troposphere and the stratosphere. The boundary moves closer to the surface in cold weather and is typically lowest at Earth’s poles and highest at the equator.

On the second of two unusually cold days in Madison, Petty gathered with a group of students and colleague Ankur Desai at sunrise on University Bay. Temperatures hovered around minus 24-degrees Fahrenheit. They filled a weather balloon with helium in preparation to gather measurements of temperature and humidity for several miles above Earth’s surface. Photo by: Jeff Miller

The weather balloon was used to send this radiosonde up to 20 miles above Earth’s surface. The instrument is equipped with sensors designed to gather temperature and humidity data as the balloon ascends, transmitting that data back to Petty’s computer. With it, he can also determine the location of the tropopause, the boundary between two layers of Earth’s atmosphere called the troposphere and the stratosphere. Photo by: Jeff Miller

Petty explains how the radiosonde will gather data as it transits Earth’s atmosphere collecting temperature and humidity measurements. Petty took advantage of unusually cold temperatures to launch the instrument and determine the location of the tropopause, the boundary between Earth’s lowest atmospheric layer, the troposphere, and the next layer, called the stratosphere. The boundary moves closer to Earth in colder conditions. Photo by: Jeff Miller

Students stand on frozen Lake Mendota poised to launch the weather balloon, now equipped with the radiosonde. Petty checked that the instrument was transmitting data to his computer and gave the students instructions prior to launch. Photo by: Jeff Miller

Upon the signal from Petty, the students released the weather balloon carrying the radiosonde. Petty immediately began to capture data from the instrument, which he could see on his computer. The balloon would travel as high as 20 miles above Earth’s surface and as far away as 100-miles before bursting and returning to the ground. The radiosonde would continue to transmit data, which Petty would analyze later to determine atmospheric conditions above Madison on an unusually cold winter day. Photo by: Jeff Miller

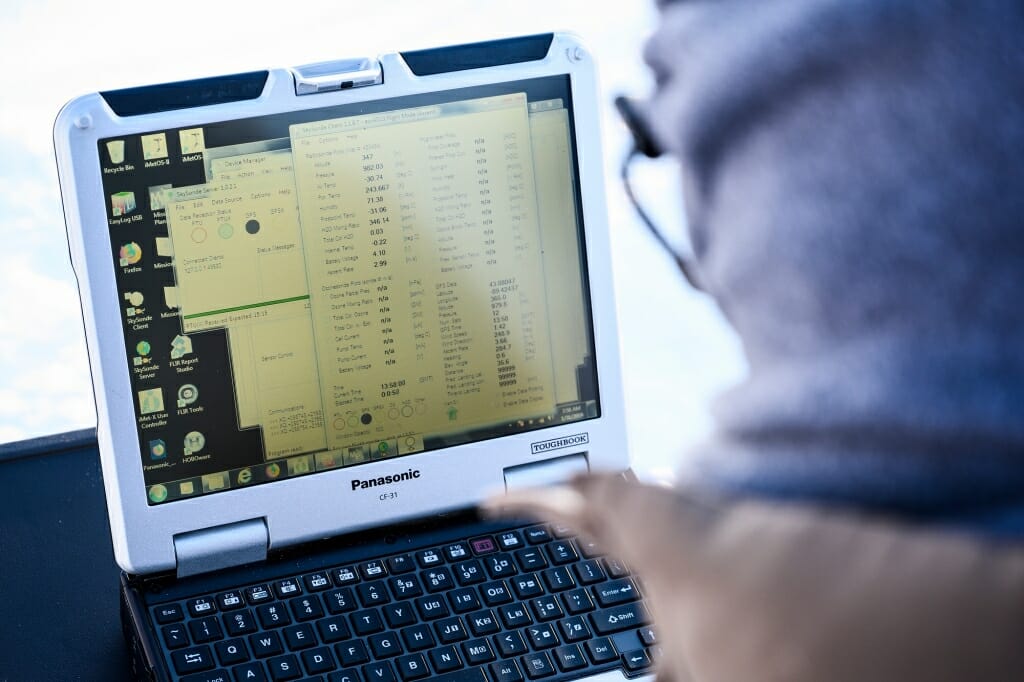

The radiosonde, traveling upward from Earth’s surface, transmits data back to Petty’s computer in real time. With that data, Petty can plot changes in temperature and humidity and also determine the location of the boundary between Earth’s troposphere and the next layer, called the stratosphere. The troposphere reaches about six miles above Earth and contains most of the planet’s weather and clouds. Planes generally travel in the stratosphere in order to avoid some of the turbulence in the troposphere. Photo by: Jeff Miller

Students huddle around Petty as he explains some of the data the radiosonde is transmitting from the atmosphere as it travels on the weather balloon they launched minutes prior. Photo by: Jeff Miller

Icicles are visible on the eyelashes and clothing of graduate student Brian Zimmerman. Temperatures at sunrise on University Bay hovered around minus 24-degrees Fahrenheit and students bundled up to keep warm. Photo by: Jeff Miller