Geoheritage and groundwater focus of twin Badger Talks during Wisconsin Science Festival

Layers of cobblestones at Parfrey’s Glen State Scientific Area show material deposited during turbulent water flow in storm-tossed water, while the fine-grained sedimentary rocks formed in calmer water, nearly 500 million years ago. Photo by David Tenenbaum

The role of rocks and water in the past and present of the Badger State will be highlighted in a pair of Badger Talks by someone who knows what he’s talking about.

In Antigo Oct. 16, Ken Bradbury, director of the Wisconsin Natural History and Geologic Survey, will discuss “Geoheritage.” The talks will begin with the origins of the state’s physical foundation, and move to past and present human uses of those rocks.

Badgers Talks are a series of talks statewide by University of Wisconsin–Madison experts on many topics, aiming to spread knowledge from the state’s flagship campus.

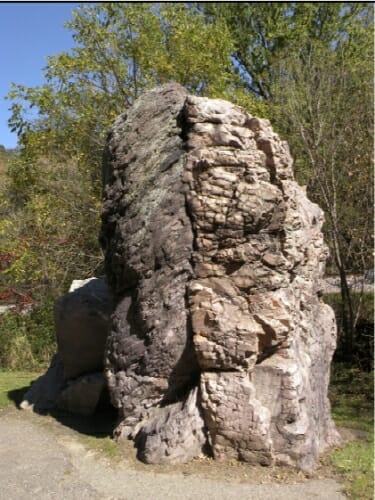

The Van Hise rock, named for geologist and former University of Wisconsin president Charles Van Hise, is near Rock Springs, Wisconsin. This rock has long been used as an example of key principles of structural geology. The rock layers were deposited horizontally, but have been folded vertically upward by tectonic forces. Photo courtesy of Ken Bradbury.

Beginning with the beginning, Bradbury will discuss “basement rocks” that remain visible in selected locations. Bradbury will describe the rare places in the state where these relics – aged almost 3 billion years — can be seen on the surface. He will also dig through the history of mining:

- The “Badgers” who started to dig lead in Grant and adjacent counties in the 1820s, and gave the state its nickname;

- Iron mines, such the abandoned mine that formed 300-foot-deep Lake Wazee in Jackson County, a popular spot for enjoying clear, clean water – courtesy of the mining industry; and

- The springs in Waukesha (once known as “Spring City”), which were the target of a scheme to pipe the spring water to Chicago for the 1893 Columbian Exposition (an early world’s fair). The plan was drowned by political opposition in Spring City.

On Oct. 17 in Augusta, Wisconsin, Bradbury will talk about groundwater, wetlands and surface water. “A lot of people see wetlands and see neat plants and animals, but they don’t necessarily think about why they are there; why they are in that place,” he says. Bradbury has studied Wisconsin wetlands for more than 30 years.

Donald Park, in southern Dane County, has a number of springs, including “Big Spring,” shown here near an observation platform. Wisconsin Natural History and Geologic Survey

“Wetlands are part of the hydrologic system,” Bradley explains. Wetlands can be either a discharge space where groundwater enters a stream, or a recharge place, where rainfall enters the groundwater.

Or they can serve both functions, depending on conditions.

Wetlands, Bradbury adds, store water during floods and release it slowly, acting as natural sponges and refuges for wildlife.

Building on these concepts, Bradbury will talk about two threats to groundwater. Neither pollution nor excessive extraction through wells can be fully understood while ignoring the big picture, Bradbury says. “It’s a misconception that wetlands are purely surface-water features. People don’t understand that they are almost always part of a groundwater system, and so when people do things to groundwater, like pump a high-capacity well, that can affect wetlands, dry them up. We’ve clearly seen this in Central Wisconsin, even in Dane County in dry years.”

Speech details:

Oct. 16 in Antigo: “Wisconsin’s Geoheritage, ” 5:30 p.m., Antigo Public Library, 617 Clermont St, Antigo.

Oct. 17 in Augusta: “Groundwater and Wetlands: The Hidden Links,” 5 p.m., Augusta Memorial Public Library- 113 N. Stone St, Augusta.