For students who worked on Public History Project, a rich and often emotional experience

Public History Project Director Kacie Lucchini Butcher, left, and Taylor L. Bailey, who began working on the Public History Project as a UW–Madison graduate student and became its assistant director after receiving her master’s degree in Afro-American studies in May 2022. Photo: Jeff Miller

When Taylor L. Bailey first heard about UW–Madison’s Public History Project, she remembers being intrigued — and more than a little surprised.

“Universities usually shy away from acknowledging any pain they’ve caused,” says Bailey, who came to UW–Madison as a graduate student in 2020.

Bailey’s curiosity led her to learn more about the project and to meet with Kacie Lucchini Butcher, the project’s director. During Bailey’s second year on campus, she became a student researcher for the project — one of more than two dozen undergraduates and graduate students who have helped shape the initiative since its inception in 2019.

“I feel like that’s the beauty of the project,” Bailey says. “We’re highlighting student experiences in the history of the university, and students themselves have been a big part of the process every step of the way.”

The Public History Project is a multiyear effort commissioned by former chancellor Rebecca Blank to uncover and give voice to those who experienced and challenged bigotry and exclusion on campus and who, through their courage, resilience, and actions, have made the university a better place. The project was one of several responses to the findings of a campus study group that looked into the history of two UW–Madison student organizations in the early 1920s that bore the name of the Ku Klux Klan.

Edward Frame

In September, the Public History Project opened “Sifting and Reckoning: UW–Madison’s History of Exclusion and Resistance,” an exhibit at the Chazen Museum of Art that runs through Dec. 23, 2022. For the students who worked on the project, the experience provided valuable professional growth and an opportunity to contribute to a university effort of unprecedented size, scope and visibility.

“I was able to hone really important skills as a public-historian-in-training on a chancellor-initiated effort that has a lot of money and energy behind it,” says Edward Frame, a graduate student in history who researched the 1969 Black Student Strike and campus ethnic centers. “I don’t expect to have an opportunity like that again any time soon.”

Crucial contributors

From the start, students have been involved as crucial contributors, says Lucchini Butcher, who was hired as the project’s director in 2019. Student researchers on the project are paid an hourly wage and typically work five to 20 hours per week over the course of a semester or academic year.

“The students here have a natural connection to the university, and we found they were highly engaged and passionate about doing research about the institution,” says Lucchini Butcher, a public historian and award-winning museum curator from La Crosse, Wisconsin. “The ability to think critically and to do historical research are key skills that our students need, and this project gives them that experience. They can ask difficult questions and do research that they feel is necessary and, in many cases, represents their own communities.”

Dustin Cohan

Lucchini Butcher worked with students to choose research topics that interested them or aligned with their degree programs. Dustin Cohan, a history PhD student who studies Latinos in Wisconsin, says he appreciated this collaborative approach. He conducted more than 20 oral history interviews for the project and wrote about the effort to create a Chicano Studies Department at UW–Madison.

“It’s one thing to have a job as a graduate student that pays the bills,” Cohan says. “It’s quite another to be able to work on a project that’s highly relevant to your research and to the lives of so many people. It helped me crystallize my own thoughts about my area of research, and I met a ton of people I would not have met had I not had this opportunity.”

Doing the work

Kayla Parker learned about the project in a public history seminar taught by Lucchini Butcher. Parker was a sophomore at the time and already doing research for a class assignment on blackface incidents at fraternities throughout the 20th century. Lucchini Butcher hired her to continue researching fraternity and sorority life on campus, which led to a blog post written by Parker on the formation of Black Greek-letter organizations at UW–Madison.

Kayla Parker

To get to the finished product, Parker spent many solitary hours at Steenbock Library sifting through nearly 100 boxes of UW Archives material, including decades-old meeting notes from Interfraternity Council meetings. “You look through pages and pages of irrelevant material before you find something that’s really interesting,” Parker says.

It wasn’t glamourous work, but it was deeply impactful and professionally invaluable, says Parker, who graduated in May with a bachelor’s degree in history and political science.

“When I was at UW–Madison, I was part of the minority community, and some of those stories really made me realize how different it was for minority students back in the 60s,” Parker says. “It was a good reminder of how far we’ve come and how much farther we must go.”

Personal toll

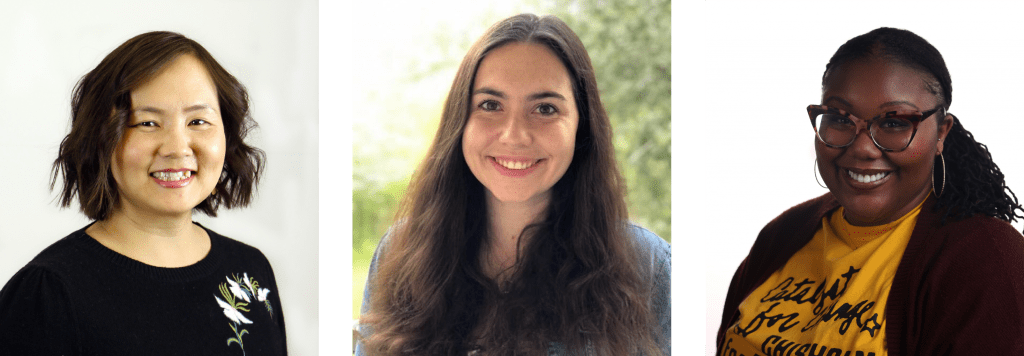

From left, Chong Moua, Zada Ballew and Angelica Euseary (Euseary photo by Marlita Media).

Chong A. Moua, a history PhD student who chronicled the experiences of Hmong American students on campus, hopes the Public History Project marks a turning point for the university.

“The question now is, ‘How far is this going to go?’ Is this simply an acknowledgement on the university’s part that these things happened, or can it be something more sustainable — a moment when real change occurs?”

Zada Ballew, a history PhD student who researched the history of Native American students at UW–Madison, found that conducting oral history interviews with Native students and alumni was both rewarding and emotionally draining.

“This is an exciting time on campus because Native students are willing and ready to tell their stories and UW is ready and willing to hear them,” says Ballew, an enrolled citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi. “But as rewarding as this process is, it has also been incredibly difficult to reckon with the stories they’ve told me and to sit with the weight of that history.”

Angelica Euseary, a recent alumna who researched the safety of Black women on campus, says that while the people she interviewed were excited to tell their stories, many were “retraumatized by the trauma” they shared with her. The experience caused Euseary to reflect more deeply on her own experiences as a Black student at UW–Madison.

“It was a lot to process,” says Euseary, who completed a master’s degree in Afro-American studies at UW–Madison in 2021. “If I was going to interview someone, I didn’t schedule anything else the rest of the day. I wanted to honor their stories by not overextending myself.”

Bailey describes the work she did as emotionally taxing. “It wasn’t fun to spend hours and hours reading about discrimination,” she says. “That’s sort of the unfortunate side of taking on a project like this. But this is work that needs to be done. We need to reckon with this history.”

Bailey began her work on the project by researching the influence of the national Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in the Madison community in the early 20th century. She became interested in museum curation and shifted to helping write the stories that would end up as museum copy in the exhibit.

While still a graduate student, Bailey became a project assistant. Then, after graduating in May with a master’s degree in Afro-American studies, she was hired as the project’s assistant director. She is on leave from a PhD program in English to work full time for the project.

“It’s been a very emotional experience,” she says. “I’ve been preparing myself for how I’ll respond to the reactions people have to the exhibit. I just hope the emotional labor that my colleagues and I put into this work is not in vain and that a lot of action comes from putting this history on display.”

Tags: history, Public History Project, students