Curious Madisonian still innovating, designing, improving 35 years after UW-Madison graduation

Testing some virtual-reality goggles is just another workday for Madison innovation specialist and UW–Madison grad Bruce Winkler. David Tenenbaum

In his basement offices in Madison’s near-west side, Bruce Winkler is unpacking airfreight shipments. One, ominously marked “not for passenger aircraft,” contains large lithium-ion batteries for a floor sterilizer that he wants to be ready for market once the price of the key LED light makes it affordable.

The second box contains a cardboard object that supposedly folds, origami-style, into augmented reality goggles. Like the average person, Winkler struggles to find the first fold.

But an office jam-packed with techno-curios demonstrates that Winkler is hardly average in the mechanical-electronic-digital realm. One shelf holds complicated metal puzzles – collected for his own amusement — that are unsolvable – until you abandon your ingrained approach to the solution. Nearby, a plastic cylinder houses streams of silver balls with a magical, mesmerizing movement.

And then there are the things that Winkler has invented, designed or facilitated in a 35-year career of bringing innovations to market, since he earned his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from UW–Madison in 1983. These include dozens of lighting products, goggles, phone apps, exercise bikes, and a bottle that transmogrifies into a glass.

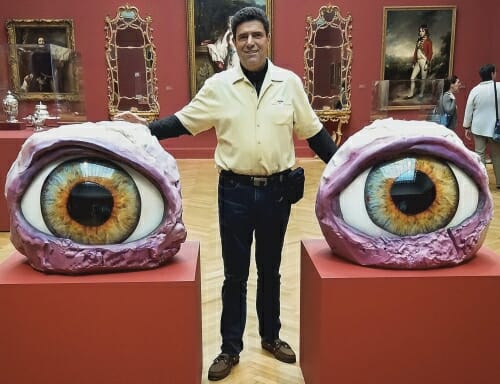

Eyes on the prize: Bruce Winkler has been inventing, prototyping and bringing ideas and technology to market ever since he graduated UW–Madison with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1983. Submitted by Bruce Winkler

His offices no doubt hide the money-mutilator he built so the U.S. Treasury could project the working life of paper money. There’s one of the “gene zappers” he built for geneticist Oliver Smithies 30 years ago, which may have helped Smithies create the “knockout mice” that won him a Nobel. Smithies created the mice, which were used to identify the function of specific genes, at UW–Madison.

These days, Winkler doesn’t just help build objects. His smartphone, for example, hosts a virtual-reality display built for Bock Water Heaters, a Madison manufacturer of commercial water heaters. The device allows the viewer to “fly through” (should we say “swim through”?) a water heater to see its features. “It gives us a more state-of-the-art feel,” says Bock’s head of marketing Jerry Albright. “At trade shows, we hold a cocktail party, and our invitation says, ‘Come to virtual reality night.’ Bruce has a way of being ahead of the curve. It’s been a good ride for us.”

If da Vinci had a pen and parchment, and Edison had vast chemistry labs and mechanical workshops, Winkler has a five-screen computer leading to a network of suppliers and innovation resources in the United States and at least five other countries.

For the water-heater app, he says, “I found two programming resources, from Indonesia and India, that wanted the 3-D work. I hired both firms for a small part. Whoever did the best job got the whole job.

“Hiring virtual talent requires a ‘What? By when? For how much?’ mentality,” Winkler says.

A la carte engineering help also built “Web Racing,” a Winkler business that enables people to race on Internet-enabled exercise machines, and view the experience on a flat screen.

Brucewinkler.com brings ideas to market. For an invention designed to allow a wheelchair user to roll into a vehicle’s driver’s position, Winkler tried to reduce cost by locating a cranny in the vast American economy with expertise in the most difficult component. “Don’t try to reinvent the wheel,” he suggested.

Through Assistra Technologies LLC, Winkler consults on universal accessibility of kiosks – self-service stations used at airports, post offices, Homeland Security border crossings, downtown street corners, the Social Security Administration and elsewhere. Although these kiosks are subject to the Americans with Disabilities Act, many do not make the grade.

An older keypad design for a kiosk is confusing to anybody who must rely on voice cues to find the correct button. Assistra Technologies LLC

Inline design follows EZ Access protocols developed at UW–Madison, simplifying use by the visually impaired. Assistra Technologies LLC

For this work, Winkler has licensed 12 accessibility patents from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. Inventor Gregg Vanderheiden, who advanced universal design at UW–Madison’s Trace Center for decades, says, “Bruce is an incredibly creative individual who is really interested in the mission of accessibility of information and communication technologies. We tried several times to create relationships with other kiosk vendors and developers, but none came close to either the understanding or commitment that Bruce has shown,” adds Vanderheiden, who is now at the University of Maryland.

Winkler is a tall, intense man with a booming voice and a fountain of enthusiasm who plays piano (from Beethoven to Billy Joel) for an hour a day. While growing up in the Chicago suburbs, he played with Erector and chemistry sets, but the interest “was not structures so much as curiosity,” he says. “When a guy came to fix the air-conditioner, I wanted to know what made it work and why it was broken.”

Skimming Winkler’s website (www.ideatomarket.com) shows how this curiosity spawned an astonishing range of advice, design and invention:

- Genetic engineering instrumentation;

- A device to improve boating safety;

- A fiberglass island with sensors and controls, for remote controlled boats at Sea World; and

- A sensor system to keep the elderly from getting bed sores.

In a trans-generational tactic, Winkler is helping his college-age son, James, develop a bottle designed to spray to the last drop. He’s starting to travel more with his wife, Carol, a psychotherapist who recently retired from an intense job working with social pariahs.

Not that retirement is approaching for Winkler, 57. He’s having too much fun as projects come in the door from seemingly every direction.

Soon, he will spend a week setting up technology for the Helix Cup, a multimedia “wow fest” and science contest sponsored by biotech giant Genentech in San Francisco. It doesn’t deal directly with any of Winkler’s businesses, but it does exploit his technical and organizing abilities.

And it plays to his inner showman, a talent he honed during the years spent advising Madison performing arts companies about lighting. And the contest no doubt lets him meet kids who just might have the same exploratory, can-do spirit as the young Bruce Winkler.

“It always seems impossible. Until it’s not.” It’s a tagline for his business. And it applies to the proprietor, who, as one of Madison’s foremost practitioners of the art of the possible, has a preposterously broad range of interests, expertise and possibilities.

Tags: alumni, engineering