Conservationist reminds us: Aldo Leopold still relevant today

Aldo Leopold and his wife, Estella, in 1943. Leopold treasured time outside with students, colleagues and his family. UW-Madison Digital Archive

MADISON – Noted conservation biologist and longtime University of Wisconsin–Madison professor Stanley Temple is often asked how he remains hopeful despite rising threats to biodiversity.

Temple’s answer is rooted in the life and writings of Aldo Leopold, who was the world’s first professor of wildlife management at UW–Madison, and is best known for his 1949 book, “A Sand County Almanac.”

Leopold developed a “land ethic” as a philosophical basis for decisions that affect Earth and life on the planet. Leopold offered a golden rule to inform every interaction with nature: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

“A Sand County Almanac,” Temple says, remains one of the most influential environmental books of all time, helping to kickstart environmentalism of the late 1960s.

From 1976 to 2008, Temple held the same professorship in the Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology that Leopold held from 1933 until his death in 1948. Stanley Temple also serves on the board of directors for the Sand County Foundation.

Now, as a professor emeritus and senior fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation, Temple gives dozens of “Leopold talks” each year around the state and beyond.

Like Leopold, Temple has observed the timing of seasonal events like the flowering of plants and migration of animals – a field called phenology. “Leopold had a lifelong passion for recording seasonal events in the natural world and interpreting their meaning,” Temple adds. “He once wrote, ‘Keeping records enhances the pleasure of the search and the chance of finding order and meaning in the events.”

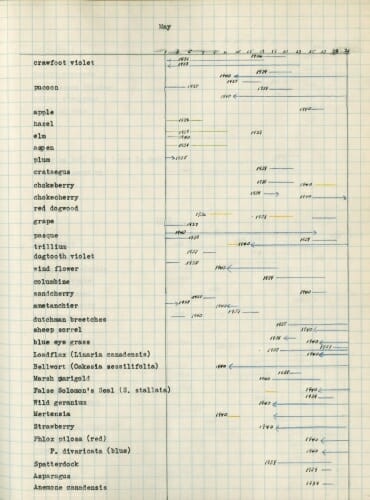

Decades later, this meticulous record of flowering dates from 1937-1940 helped Aldo Leopold’s daughter to document the ecological effect of climate change. Photo courtesy of Leopold Archives

In 1996, Temple helped Leopold’s daughter Nina Leopold Bradley comb through Leopold’s records to show that many birds were arriving earlier, and many plants are blooming earlier, than they did six decades previously. Temple’s talks on phenology have been of special interest because of what Leopold’s records reveal about response to climate change.

As Leopold moved from his early career doing field work for the U.S. Forest Service to becoming the world’s first professor of wildlife management in 1933, he was blossoming from conservation practitioner to conservation philosopher, Temple explains.

Aldo Leopold working in the Apache National Forest in Arizona, about 1910. UW-Madison Digital Archive

As a scientist with a poetic pen, Leopold focused on the broad implications of the growing public disconnect with nature. He concluded that education about environmental damage alone would not change people’s behavior. Instead, Temple says, ecological knowledge had to be coupled with what Leopold called an “ecological conscience,” a moral compass guiding us in how to live on planet Earth without spoiling it.

“Ecology,” Leopold wrote, “is the science of biotic communities, and the ecological conscience is therefore the ethics of community life. An ecological conscience is an affair of the mind as well as the heart.”

“Throughout my career,” Temple says, “I have been inspired by Leopold’s wisdom, which allowed me to remain hopeful, in spite of the odds.”

Temple gives a range of talks on Leopold – covering, for example, natural soundscapes and what Leopold called “The oldest task in human history” — how “to live on a piece of land without spoiling it.”

“My goals in these talks,” Temple says, “is help people gain both ecological knowledge and an ecological conscience so they can remain hopeful in a wounded world.”