Born of activism, UW’s Afro-American Studies Department celebrates 50 years of scholarship, teaching excellence

As an undergraduate at Northern Illinois University in 1967, Freida High recalls spending months in a contemporary art class studying painters and sculptors, all of them white. Finally, toward the end of the semester, she politely raised her hand.

“When will we get to the Black artists?” asked High, the only Black student in the class.

“There are none,” the professor responded.

The answer shocked High, and she suspected the professor was wrong. Indeed, academia was about to be jolted into change.

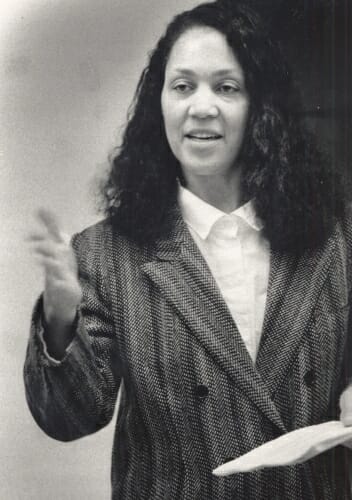

Professor Freida High, pictured in the classroom in the late 1980s, served on the steering committee that created the Afro-American Studies Department. She later joined the faculty, becoming the department’s longest-serving faculty member at 41 years. Courtesy of UW–Madison Archives

Emboldened by the Black Power Movement of the 1960s, African American students across the country demanded to see themselves in university curricula, as did students from many other marginalized groups. High played a role herself. As a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, she served on the steering committee that led to the creation of the Afro-American Studies Department in the fall of 1970. Similar efforts sprouted nationally.

“We were radically reshaping universities across the country,” says High, who later joined the UW department and went on to become its longest-serving faculty member.

Five decades after its founding, UW–Madison’s Afro-American Studies Department is being recognized this year for its contributions to campus — both scholarly and social — and for its groundbreaking work nationally. It was among the first such academic departments in the country.

“It is with great pride and appreciation that we celebrate the Afro-American Studies Department and its 50 years of superb scholarship, teaching and mentorship,” says Chancellor Rebecca Blank. “The department has been successful for many reasons — chief among them are top faculty who teach some of the most popular interdisciplinary courses on our campus and a deep commitment to offering undergraduate and graduate degrees as well as certificate programs that draw students from across disciplines. Now more than ever, we need the department’s knowledge and expertise to educate us about our country’s past and to help us create a more equitable future.”

In July, as part of a broader initiative addressing racial inequities on campus, Blank announced $1 million in funding this academic year to support faculty and employees whose research helps people understand race in America.

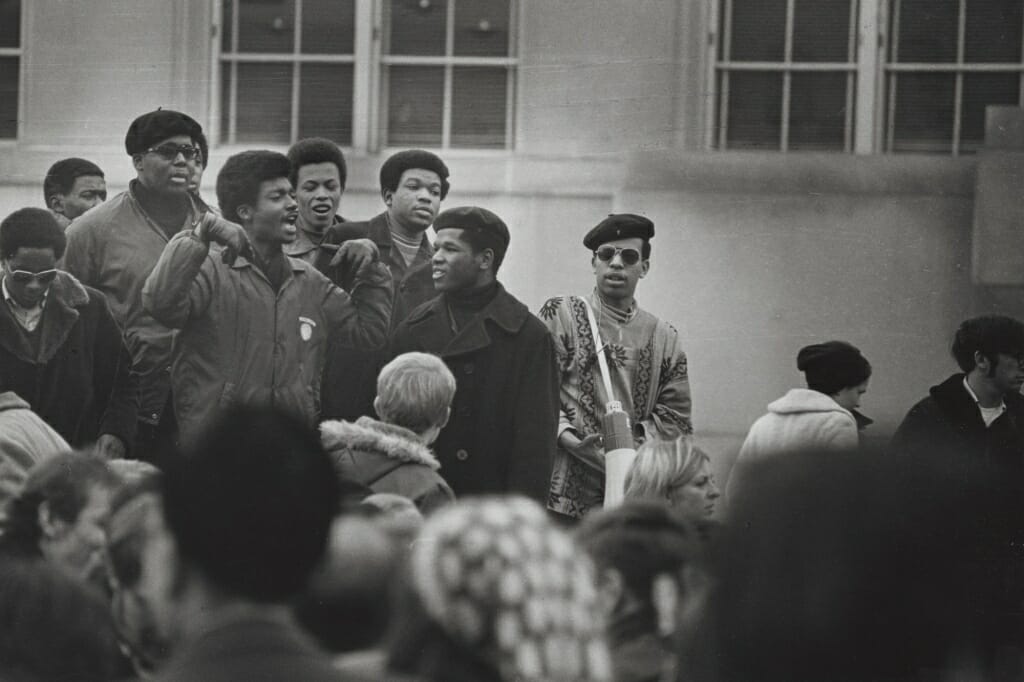

Some of the leaders of the Black Student Strike of 1969 gather to speak at a rally. UW-Madison archives

Born of activism

The Afro-American Studies Department is considered one of the most tangible outcomes of the campus Black Student Strike of 1969. Protesters presented the administration with 13 demands. A Black Studies Department led the list.

“It’s a special department because it’s a bottom-up department, not a top-down department,” says Associate Professor Christy Clark-Pujara, who joined the department’s faculty in 2010 and directs graduate studies. “It exists because students demanded that it exist.”

The department stood out nationally from the start. While other universities were developing Afro-American Studies programs at the time, very few were creating full departments — a critical distinction, says Professor Sandra Adell, a literary scholar and theater historian who has been a department faculty member since 1989. University departments are able to award degrees — students can major in the discipline — and grant tenure to faculty members.

“The student protesters were astute enough to know that a program could disappear easily,” Adell says. “They demanded a department. It was non-negotiable.”

Sandra Adell, a professor of literature in the Department of Afro-American Studies, speaks to a crowd of more than 100 people during a dedication ceremony for the new Black Cultural Center at UW–Madison on Feb. 28, 2017. Photo: Bryce Richter

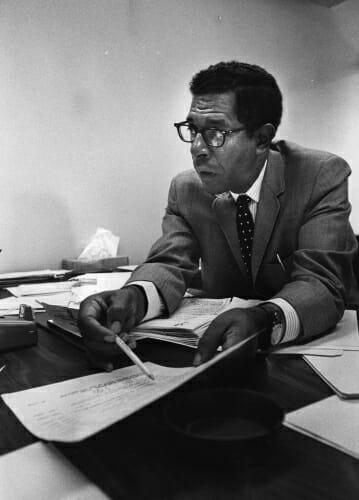

In introducing the department to campus in 1970, Professor Charles Anderson, its first chairman, said Afro-American Studies would take an interdisciplinary approach, utilizing all the university’s resources. The department offered 10 courses its first semester, taught by four full-time professors and three with joint appointments. The courses focused broadly on three themes: Black history, Black society, and Black culture and literature — topics that “traditionally have been slighted by the American educational establishment,” the department said.

Expanding into other areas

For its first decade, the department awarded only bachelor’s degrees. In 1980, it began offering a master’s degree in Afro-American Studies, a rarity nationally. Today, the department also offers an undergraduate certificate — the equivalent of a minor — as well as “bridge” programs that allow its graduate students to transition directly to doctoral programs in history and English.

Professor Charles E. Anderson served as the first chairman of the Afro-American Studies Department. A noted meteorologist, he took a leave of absence from his post at UW’s Space Science Engineering Center to help launch the department. Courtesy of UW–Madison Archives

Another dramatic change came in 1989 when the university began requiring all incoming freshmen and transfer students to take at least one three-credit ethnic studies course. Administrators leaned heavily on the Afro-American Studies Department to help students meet this requirement. Some of the department’s courses are now among the most popular on campus, including ones on African-American history and hip-hop music.

As the department expanded over the years, its focus came to include not only Black-white relations in the U.S., but the history, culture and relationships between African Americans, Africans, and other people of color wherever they are found. The department strengthened its studies in African American literature and culture and ventured into visual and theatrical studies as well as written and oral culture.

Black women’s studies became one of many strengths, with Nellie McKay, Stanlie James, Freida High and Christina Greene developing the area within the department. McKay, who died in 2006, is perhaps best known as the co-editor with Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates of “The Norton Anthology of African American Literature,” published in 1996. The work was instrumental in solidifying black authors in the American literary canon.

High, an art historian and artist with expertise in African American and African art history and feminist art criticism, joined the faculty three years after serving on the steering committee that planned the department. She initially was hired as an artist-in-residence and assistant professor, subsequently tasked with establishing the undergraduate curriculum in Afro-American and African art history. Now a professor emerita, she served 41 years on the faculty.

“It took research, commitment, innovation, and collaborative work to make Afro-American Studies the distinctive department that it is today,” High says. “The success of our students in the U.S.A. and elsewhere bears witness to the department’s success. Just as it takes many stars to light the sky, it took many faculty members to make the department what it is today.”

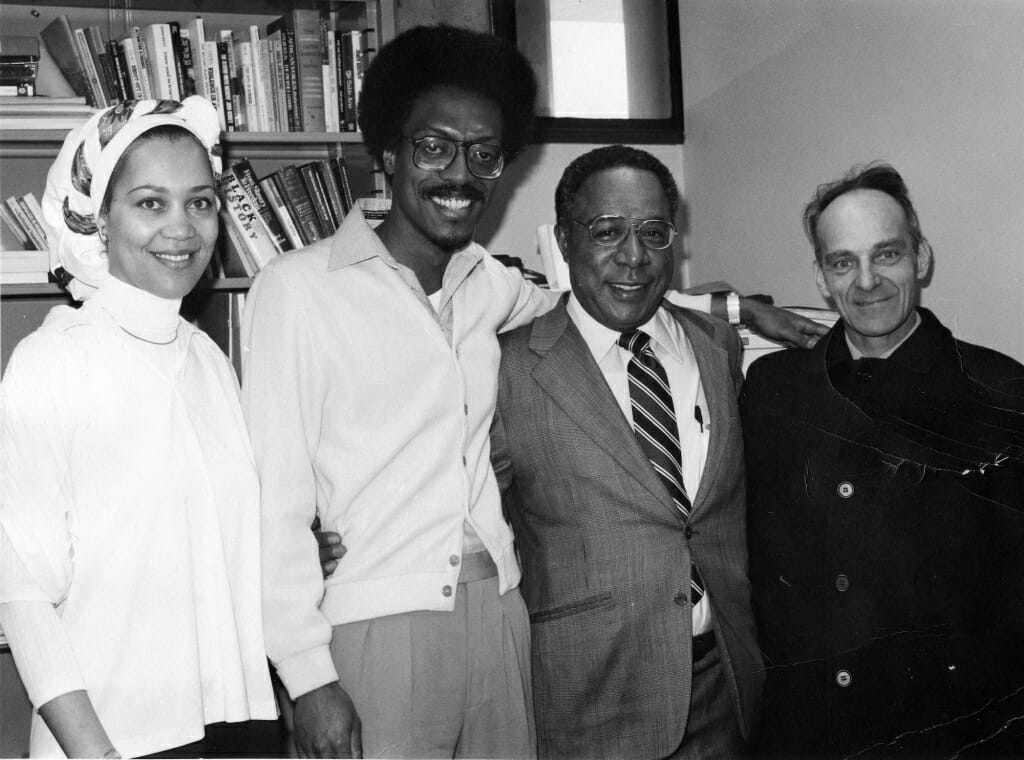

Alex Haley, third from left, author of “Roots,” visited the UW’s Afro-American Studies Department in the 1970s. Pictured with him, from left, are department professors Freida High and Tom Shick and Jan Vansina, a history professor and a leading scholar in the African Studies Program. Vansina had been a consultant for Haley on “Roots.” Collection of Freida High

The department understood from the beginning that its mission was to nurture the next generation of African-Americanists, says Professor Craig Werner, who retired in 2019 after 36 years with the department, 13 of them as department chairman.

“We wanted to help institutionalize Black studies locally and nationally and we’ve done that,” he says. “Our students have been spectacular.”

Among the department’s notable alumni: artist and activist Verlena Johnson; Melvina Young, a senior editor at Hallmark Cards; Tanisha Ford, an award-winning historian and cultural theorist; Diallo Shabazz, a global education advisor; poet and novelist Ed Pavlić; Danielle McGuire, a prominent author and historian of racial and sexual violence; and the Rev. Alex Gee, founder of Madison’s Fountain of Life Covenant Church, the Nehemiah Center for Urban Leadership Development and the Justified Anger Coalition.

More than two-thirds of the department’s master’s degree students go on to earn doctoral degrees.

Dual role on campus

From the department’s inception, many viewed its function in both academic and social terms. It is valued for its scholarship, but also for attracting diverse students and faculty and for educating the entire student body about race and racism. The handbook for Black students published in 1972 by the campus Afro-American Center described the landscape bluntly: “The student body consists of a majority of northern whites who have rarely, if ever, had any contact with Black people.”

This dual role continues today. “Every semester, I’m aware that I have students in my classes who have never had a professor of color before and who know African Americans only through movies and music,” Adell says.

Christina Greene, an expert on women in the Civil Rights Movement and a recent department chairwoman, says one of the things that is so satisfying about teaching Afro-American Studies on a majority white campus is the epiphanies and lights that go on for both white students and students of color.

“That’s deeply rewarding, maybe even more so in this political moment that’s so divisive, especially around racial issues,” Greene says. “It’s a privilege, though also difficult at times.”

Emeritus Professor Michael Thornton, who taught sociology in the department for 31 years and retired in May, says many academic departments focus more on theory and concepts and less on how their disciplines relate to people’s real-life struggles. For Afro-American Studies, the two go hand in hand.

“The power of ethnic studies is that it doesn’t allow itself to be just ensconced in the classroom,” says Thornton, who developed a popular community-based service-learning course. “It’s a conduit to social change. An extension of that is that many of our faculty members are heavily involved in the community.”

Michael Thornton teaches a class in the Mosse Humanities Building on Feb. 21, 2018. Photo: Bryce Richter

One challenge for the department is to keep its scholarship going while also meeting these added expectations, Thornton says.

“Historically, we’ve often ended up being the primary source on campus for understanding race relations,” he says. “That can create a bit of a dilemma for a department. You become a real workhorse for the university.”

Looking ahead

Today, the department has 10 faculty members and many more instructors and affiliated faculty members from across the campus. This fall, the department is offering 24 courses, with a combined enrollment of 927 distinct students.

Ongoing national protests over police brutality and racial inequities underscore the importance and necessity of the work done by the Afro-American Studies Department for 50 years, says Clark-Pujara, whose research focuses on the experiences of Black people in French and British North America in the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries.

“I think what is happening across the country will further heighten student curiosity about where we are as a country, and the department will play an important role in contextualizing how we got here,” she says.

One of the classes Clark-Pujara is teaching this fall is Introduction to Afro-American History.

“We will be doing a deep dive into the Afro-American experience, which is horrible and beautiful,” she says. “It’s horrible because of what was done to people, and it’s beautiful because of what the people did for themselves. Afro-American history is a history rooted in constant resistance and people affirming their humanity, and I think that will really resonate with students this fall.”

Greene says she makes sure to remind students that the courses they take in Afro-American Studies grew out of the protests and bloodshed of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement, and that the struggle continues.

“I tell them to never forget that we are here because students and faculty fought for us to be here,” she says. “And they paid a price for us.”

Tags: academics, diversity, history, humanities