Book club serves up an ‘intellectual feast’ for retired faculty members

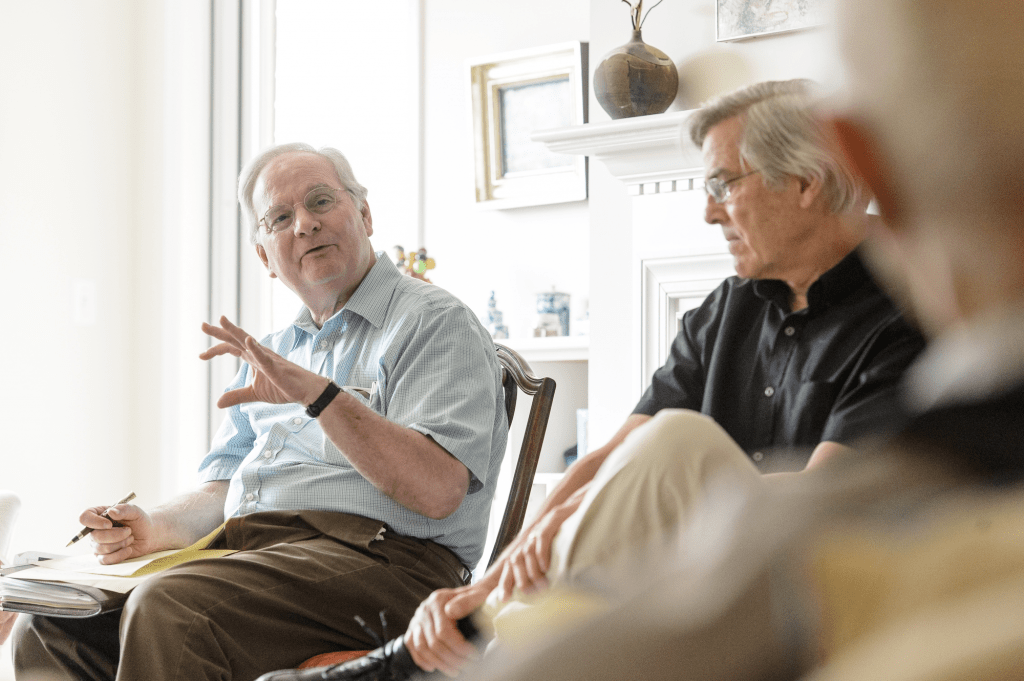

Within the Auxiliary Book Club, Rich Leffler (left), an emeritus academic staff member in the history department, is known as a stickler for research and a lover of footnotes. Bob Jeanne, a professor emeritus of entomology, listens to Leffler’s observation. Photo: Bryce Richter

They read only nonfiction books. And serious stuff, no fluff.

There are just 10 of them. When an opening occurs, a carefully considered replacement receives an invitation.

They love footnotes.

For 23 years, a group of retired UW–Madison professors and administrators has met monthly to discuss works of historic and scholarly import.

As book clubs go, it could be one of the world’s smartest.

All 10 members hold doctorates. Combined, they’ve written 49 books and taught 332 years on campus.

“Even though we’ve retired from our jobs, we haven’t retired from our intellects,” says Chuck Snowdon, 77, a professor emeritus of psychology. “I find it really valuable to continue to challenge myself, and these are some intimidating minds to interact with.”

“Even though we’ve retired from our jobs, we haven’t retired from our intellects.”

Chuck Snowdon

The group’s name, the Auxiliary Book Club, speaks to its origins. Soon after Bernard Cohen joined the political science department in 1959, his wife, Toby, joined a new book club for “faculty wives.”

“It sounds funny today, but that was a term back then,” she says. “It was uncommon for a faculty wife to work in those days. We were basically appendages of our husbands.”

Once a year, the women in the book club invited their husbands to a meeting to socialize.

“At one of those meetings, sometime in the 1990s, the men in the room looked around and realized we were all retired,” says Bernard Cohen, now 92 and a professor emeritus of political science. “We decided we should have our own book club.”

And so, in 1995, they became an offshoot. (The women’s book club continues to meet 58 years after its founding, though membership has expanded beyond the wives of UW–Madison faculty members.)

Cohen and Lee Hansen, 89, a professor emeritus of economics, are the only two founding members of the Auxiliary Book Club still active. Donald Downs, the youngest member at 69, got the call to join two years ago.

“It’s a friendly group, but also informative and somewhat demanding,” says Downs, a professor emeritus of political science.

As book clubs go, it could be one of the world’s smartest.

As befits a group of scholars, club members have kept meticulous records. They have read 221 books, 220 of which have been nonfiction.

Their one dip into fiction — the novel “Therapy” by David Lodge in 1996 — ended poorly.

“The book was terrible, just terrible. We’ll never do that again,” says Cohen, who served as acting UW–Madison chancellor in 1987. “I persuaded the group to read it. I’ve been repenting ever since.”

In the only other known instance of a novel being discussed, a subgroup once met for lunch to talk about “Stoner” by John Williams. The gathering was unofficial and somewhat clandestine. “We didn’t want to push it on the whole group,” Hansen says.

Club members lean heavily toward works of history, politics and science — books like “The Pope and Mussolini” by David Kertzer and “Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness” by Peter Godfrey-Smith.

They were so impressed with historian David McCullough’s “The Path Between the Seas,” a chronicle of the creation of the Panama Canal, that they booked a cruise and sailed the canal themselves eight months later. That’s why their March 2000 meeting unfolded aboard the Sun Princess.

“It’s a friendly group, but also informative and somewhat demanding.”

Donald Downs

Books are chosen by collective vote from recommendations made by members. While an author might consider it an honor to be chosen for discussion by such an austere group, pity the ones whose works come up short.

“Lately there’s been sort of a collective violence against the author,” says Harry Peterson, 78, a former assistant to UW–Madison Chancellor Donna Shalala and former president of Western State Colorado University. “In football, it would be called piling on.”

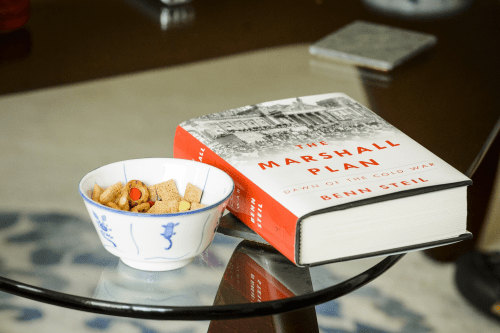

Book club members lean heavily toward works of history, politics and science, like the July selection, “The Marshall Plan” by Benn Steil.

At the July meeting, the club dissected “The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War” by Benn Steil. Cohen hosted and fired the opening shot.

“I think the author does a superb job of taking a fantastic topic and turning it into mind-numbing boredom,” he said. He went on to note numerous instances where he said the author mangled the English language, such as improperly using the word “hence.”

Cohen’s comments drew appreciative laughter — he’s known as the toughest critic in the club.

“One of Bernie’s specialties, in addition to foreign policy, is finding bad sentences,” Peterson says.

Other club members came to the author’s defense, including Richard Leffler, 72, an emeritus academic staff member in the history department who describes the book club as “an intellectual feast.”

Leffler is a stickler when it comes to research methods. His motto: Never unquestioningly trust a secondary source. Steil passed the test.

“He’s depending on actual documents, including some written and revised by people like Stalin and Molotov,” Leffler said. “That’s revelatory.”

The discussion was robust but friendly. “There are disagreements, but no fights ever break out,” Hansen says.

No one can recall a member quitting in a huff. The most common reason for an opening is death, an unavoidable aspect of a club with an average age of 78. Five members have died in the last three years.

“One of the reasons the club is so successful is that it helps you make friends with people who can speak at your memorial service,” Snowdon says, to guffaws from his fellow club members.

“We’re building up our own burials, and we bury a bunch,” adds Jay Stampen, 80, a professor emeritus of educational leadership and policy analysis.

“There are disagreements, but no fights ever break out.”

Lee Hansen

The other current members of the club are Bob Jeanne, 76, a professor emeritus of entomology, and two professors emeriti of political science, Booth Fowler, 78, and John Witte, 72.

New members must be approved by everyone in the club.

“We look for thoughtful people who won’t monopolize the conversation,” Hansen says. “There were two people who would have been very interesting but we knew they’d talk too much.”

Members say this cautiousness is one explanation for the club’s longevity. Another is the opportunity to engage with respected colleagues from different disciplines.

“One thing you miss when you retire is the constant intellectual stimulation of being in the classroom and going to conferences,” Downs says. “This is a way to still step up to the plate in a sort of semiprofessional way. My heart beats a little faster when I’m with this group, and that’s good.”