Astronomers map Milky Way by light of exploding star

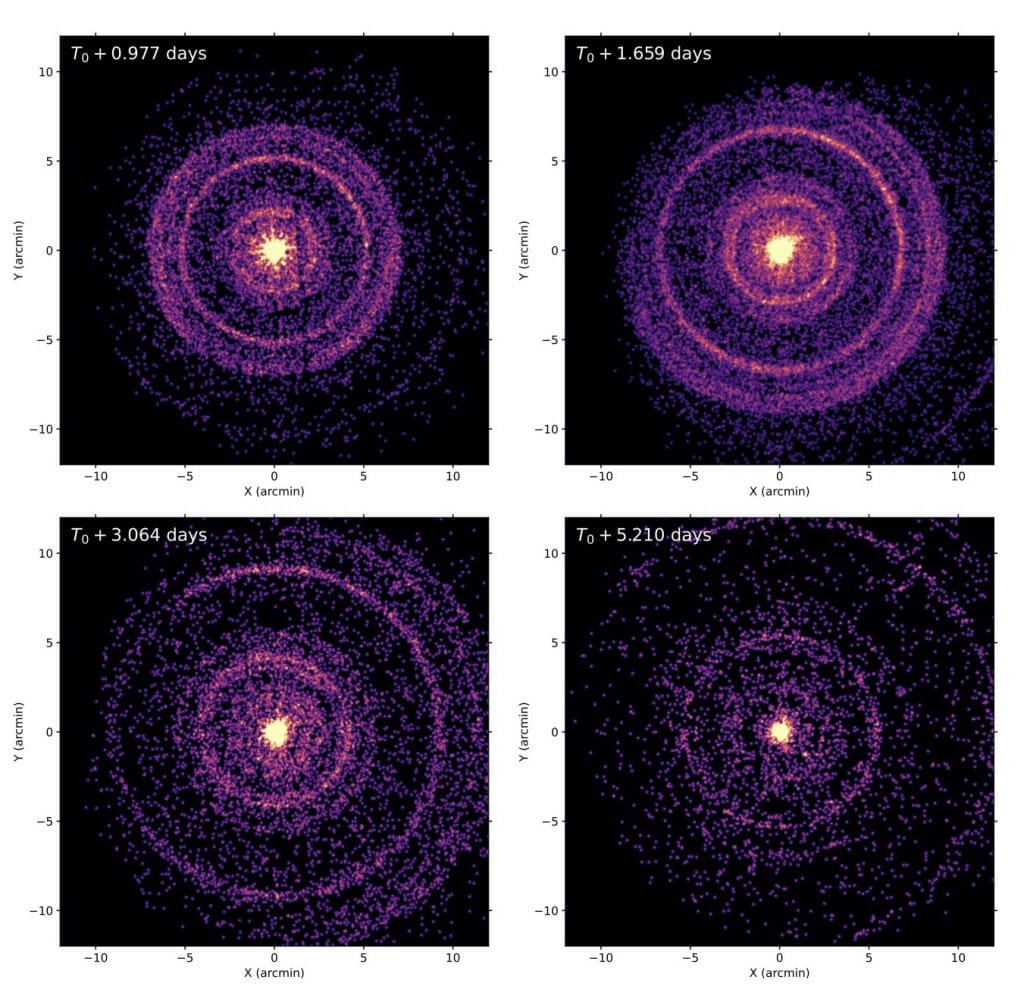

Radiation that arrived directly from gamma-ray burst GRB 221009A appears in Swift Observatory observations as a bright point surrounded, as time passed, by more and more rings from X-rays redirected by collisions with dust particles thousands of light years from Earth. UW–Madison astronomers used the data from the X-rays to pinpoint the locations of interstellar dust clouds. Image courtesy of NASA/Swift/A. Beardmore (University of Leicester)

A huge flash of radiation from an explosion outside our galaxy that reached Earth on Oct. 9 went into the record books as the BOAT — the brightest of all time.

The gamma-ray burst, known as GRB 221009A, was described in a presentation today at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s High Energy Astrophysics Division by scientists from the gamma-ray-hunting Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory

The burst of radiation has given University of Wisconsin–Madison astronomers an unprecedented look at the structure of the Milky Way and a new understanding of the sources of subatomic particles zipping through our planet. It came at nearly the speed of light from the direction of the constellation Sagitta and was picked up by many telescopes and sensors in space and around the globe, likely marking the death of a star and the birth of a black hole.

Sebastian Heinz

“These explosions are among the brightest things we see in the universe, and so intense we can see them basically halfway across the universe,” says Sebastian Heinz, a UW–Madison astronomy professor who studies interstellar dust and the physics of black holes and X-rays in space — one product of gamma-ray bursts like GRB 221009A. “This one was so bright compared to other gamma-ray bursts we expect it will be the brightest of all time for the foreseeable future.”

There likely won’t be another gamma-ray burst as bright or close to Earth for another 10,000 years, he adds, and says it’s “another 10 times less likely” that a burst this bright will be similarly located in the plane of the Milky Way.

Both the gamma-ray burst’s intensity and its path toward Earth were illuminating, Heinz says. GRB 221009A’s electromagnetic radiation came at the planet like an arrow from just a few degrees above the plane of the disk-shaped Milky Way, skimming through clouds of the galaxy’s dust on the way.

“This dust is a key ingredient of what we call the interstellar medium,” says Heinz. “It’s critical in collecting metals and heavy elements that form planets, to determining the environment around a star. Understanding clouds of gas and dust is fundamental to understanding how stars and planetary systems are formed.”

The brightest concentration of X-rays arrived on a direct path from the explosion. Other rays, on slightly different initial paths, collided with motes of dust in clouds on the way and were bounced in the direction of Earth. Because they took a longer route, those bounced X-rays arrived minutes, hours and even days behind the initial flash from slightly different angles.

“We combined all this observational data from X-rays arriving behind the first flash, and they show up as rings around the bright point of the burst — new rings for each sizeable cloud of dust the gamma rays passed through,” Heinz says. “It’s incredible and beautiful to watch it come together. The rings are like this amazing fingerprint that encodes a whole bunch of information about the galaxy itself.”

Heinz used the geometry of the late-arriving X-rays and their lag behind the initial burst to translate the rings into unprecedentedly exact locations of dust far off in the Milky Way. Each ring pointed back toward a cloud of dust, revealing both distance from Earth and relative “height” above the disk of the galaxy for scores of dust clouds.

“It gives us this tool to map out where this dust is in the galaxy as a function of distance and even now to some degree as a function of height,” says Heinz, . “We’ve mapped dust clouds with accuracy we couldn’t really have imagined as far out as 45,000 light years — some of them farther out from the galaxy than we would have anticipated.”

More analysis of the rays redirected by dust will help researchers better understand the shape and composition of the dust clouds and the Milky Way.

“We want to know how these far-off dust clouds relate to the distribution of gas and to where we see stars or don’t see stars, to where other things are happening and changing,” Heinz says. “There is an almost mind-boggling abundance of data that can tell us new things about the structure of the galaxy.”

Gamma-ray bursts have long been considered a possible source of neutrinos from beyond our galaxy, making GRB 221009A — as the BOAT — a prime potential source for the high-energy subatomic particles and thus also of great interest to scientists at the IceCube Neutrino Observatory.

“Not only was this GRB the brightest-ever detected in gamma rays, it also occurred in a region of the sky where IceCube is very sensitive,” says UW–Madison physics professor Justin Vandenbroucke, who helped lead an analysis of data from IceCube’s massive detector frozen in ice near the South Pole. These findings were also published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

However, IceCube researchers found no appreciable uptick in neutrinos passing through Earth from space, meaning even the biggest burst of gamma rays seen by Earth’s most sensitive instruments didn’t come with an attendant bombardment of neutrinos.

“These upper limits, combined with the observations from many electromagnetic telescopes, give us more information about GRBs as potential particle accelerators,” says Jessie Thwaites, a UW–Madison graduate student in physics.

Tags: IceCube, space & astronomy