App software firm with UW-Madison roots starts selling “pro” version

A UW–Madison spinoff company that makes open-source software allowing builders to code the same app for Apple and Android smartphones began on Dec. 6 to sell a service intended to remove some of the inevitable headaches linked to developing smartphone apps.

Although Ionic has sold a limited suite of services to date, it’s mainly known as the creator of Ionic Framework. This free, open-source software writes apps for smartphones and the Internet and has been downloaded about 5 million times.

Ionic Pro is the company’s first effort to sell Ionic bundled with a package of services.

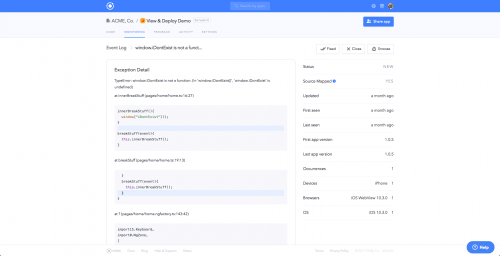

“The idea with Ionic Pro is to provide more service to help professional teams build apps more quickly, test them more quickly, and manage, maintain and update them through the entire lifecycle,” says Ionic CEO Max Lynch, who has a UW–Madison B.S. in computer science. “It will detect and help solve runtime errors in real time and help you share a test release with beta testers.”

Ionic software now has at least 250,000 active developers across the globe, ranging from hobbyists to some of the biggest names in a variety of industries, including the helicopter division of Airbus.

Ionic code was born with a recognition that eluded competitors. In 2012, when Lynch and co-founder Ben Sperry, another UW–Madison alumnus, looked at the unslakeable thirst for mobile apps, they converted two problems into opportunities. First, code written for Apple products was not useable on Google’s Android system, and vice versa. And neither one worked on a website. Second, writing code for Apple or Google entailed aptitude with a range of software languages.

Those who had those skills, called “native developers,” dominated the mobile-apps industry, but Ionic did not go after them, Lynch says. “We felt there was a big opportunity to serve web developers. Millions of them had been building websites for decades, and we decided to help them get into mobile using the skillsets they already had.”

That multitude of web developers was “not exactly a niche,” he says, “which is why I was surprised that we were only ones caring about that community.”

That approach has sprouted a firm with more than 30 employees, mostly in offices just off Madison’s Capitol Square. In 2017, Ionic opened a Boston office focused on marketing.

For more than two years, Ionic, formally known as Drifty, made its name by giving away software and offering limited consulting work to some customers. Now, with Ionic Pro, it’s adding subscription income, Lynch says.

Since Pro’s “soft launch” in August, he says, “100,000 developers have found us and signed up, and it’s growing 30 percent month over month.” Dow Jones MarketWatch builds its flagship consumer app with Ionic, Lynch says. “Our users are building a lot of serious stuff, but there is a mobile delivery gap. Many large companies have a laundry list of 50 or 100 apps that need building. Ionic gives them a way to build faster and easier.”

Ionic, like every digital-technology company, swims in a sea of change. “You can’t be in this industry and lament change, it’s inevitable, and it’s the source of your biggest opportunities,” Lynch says.

In an unexpected turn that could play directly to Ionic’s strength, Google and other bigs are looking at a new approach to mobile apps called progressive web apps. The goal is to enable faster response by stripping out the code and storing data online.

Digital platforms are seeing more time spent on progressive apps and more clicks on ads, Lynch says. Faster downloads make progressive suitable to emerging markets, where phone networks are slower.

With a progressive web app, a mobile device search brings the user to a web page that can download an app, bypassing the App Store and Google Play. “There is no gatekeeper,” Lynch says. “Developers are frustrated. To compete in the App Store, you have to go through Apple, you have to market their way on the App Store.”

Because progressive web apps are based on Internet code, “We are uniquely positioned to help teams build apps with the same exact code that will work on the web, and on the App Store and Google Play,” Lynch says. “The old style of mobile development reminds me of writing a book in German, and then writing it again in Arabic. That’s a lot of work. With Ionic, you write the book once and it automatically translates into the three languages that matter.”

Sperry and Lynch became friends in kindergarten while growing up in Shorewood, Wisconsin. While Lynch studied computers at UW–Madison, Sperry got a B.A. in fine arts.

Sperry masterminds design at Ionic, Lynch says. “Developers want to have technology and tools that make them look good, and one way you do that is to make sure the software they create looks good out of box.”

Ionic has about eight UW–Madison alumni, mainly from computer science and allied fields, and it plans to increase such hiring, Lynch says. “Madison is going to be our engineering and product home, entirely because of the university. Its graduates are the same high caliber engineers that Facebook, Google and Microsoft are trying to hire every spring at the career fair. We feel it’s an advantage to be close to that talent pool, and we try to provide a compelling reason for them to stick around.”

— David Tenenbaum, 608-265-8549, djtenenb@wisc.edu

Tags: computer science, software, spinoffs