A century on, celebrating the first Yiddish-language college course

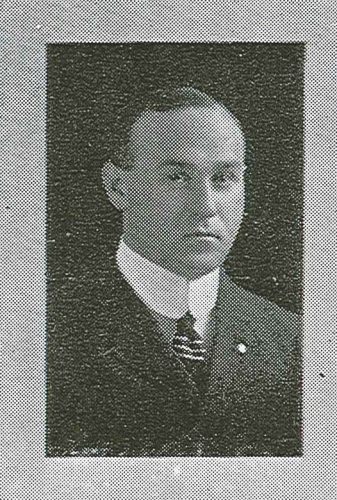

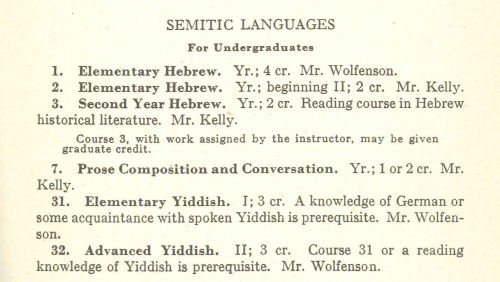

One century ago, the University of Wisconsin became the first institution of higher education in the Americas — and perhaps the world — to teach Yiddish, the language of the eastern European Jews. Louis Bernard Wolfenson, a La Crosse native and UW alumnus, started teaching the classes in the semester that began Sept. 20, 1916, in the Department of Semitics and Hellenistic Greek.

Louis Wolfenson was an assistant professor in the Department of Semitics and Hellenistic Greek at the University of Wisconsin. Photo courtesy of UW–Madison Archives

This was more than 30 years before Yiddish classes originated in a much more logical location, New York City, says Henry Sapoznik, director of the Mayrent Institute for Yiddish Culture on campus. “Wolfenson was the first person to give the language an imprimatur through a university. Columbia University in 1948 makes more sense; it was the right place, and the right time. What we’re talking about here is pretty far ahead of the curve.”

One hundred years after those pioneering Yiddish classes, the Mayrent Institute is celebrating the anniversary with a revised website featuring something even older: the oldest known recordings of Yiddish music, the folk/popular and liturgical music of eastern European Jews, and a revived program intended to keep the language alive.

“We are creating a continuity of spoken Yiddish on campus,” says Sapoznik, a Brooklyn native who is the son of Polish Holocaust survivors. “Just as Wolfenson used a new format — the classroom — we are using the website for distribution and dissemination.”

Mayrent assistant director Scott Carter played a key role in the quest for documents to explain what motivated Wolfenson to start the world’s first Yiddish classes, and to learn where he wandered after leaving Madison in 1925.

These celluloid cylinders at the Mayrent Institute contain the oldest known examples of recorded Yiddish music, dating to about 1901. Photo: Ron Wiecki, Mills Music Library, UW–Madison

When Mayrent was founded in 2010, benefactor Sherry Mayrent donated more than 9,000 78 rpm Yiddish recordings. Mayrent’s subsequent gift of 14 celluloid cylinder recordings that date to as early as 1901 includes the oldest known examples of recorded Yiddish music. The recordings are held at the Mills Music Library on campus, “which is one of a handful of major historic sound repositories in the country, one of the finest music libraries,” Sapoznik says.

All of the early cylinder recordings were transferred to CD and released in September by the Grammy Award-winning reissue label Archeophone Records. The Mayrent Institute’s copy of “Vayzuso” is the only known recording (c. 1901) from Abraham Goldfaden’s Akheshverus (Queen Esther: Biblical Operetta in Five Acts and 15 Scenes):

Wisconsin may be a surprising locale for the first Yiddish classes, but “Wolfenson did not jump-start this thing from nothing,” Sapoznik says. “Madison had a vibrant Yiddish culture. There was a Workman’s Circle (a hybrid social, cultural and progressive political organization), Yiddish theatre.”

In a 1922 article in the Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, Wolfenson described “a welcoming environment in Madison toward Jewish students,” says Sapoznik. “He made the point that he wasn’t teaching in reaction to anti-Semitism, but in a positive way. He saw Yiddish and Jewish culture as an organic part of the culture of Madison, both the town and the gown.”

The 1916-17 catalog for the University of Wisconsin listed two Yiddish courses taught by Louis Wolfenson. Photo courtesy of UW–Madison Archives

Wolfenson’s efforts to teach and support Jewish students and culture “were very much in line with the Wisconsin Idea,” says Sapoznik. “Wolfenson recognized the value of the citizenry of Wisconsin, and the importance of uplifting every one.”

Wolfenson also founded the Jewish Students Association “as a combined cultural-religious home for Jewish students that anticipated the Hillel houses that were founded just two or three years later,” says Sapoznik. “This is visionary times two. As with the Yiddish classes, he was ahead of his time.”

In 1925, Wolfenson resigned, then moved to Cincinnati to teach at Hebrew Union College. In 1927 he went to Providence, Rhode Island, and sold insurance. He was buried in Madison in 1945, which indicates that he felt his true roots were here, Sapoznik says.

Yiddish language and culture had a resurgence in Madison during the 1960s, with the arrival of Irving Saposnik (no relation to Henry Sapoznik). Saposnik left UW–Madison in 1972, but resumed teaching Yiddish when he returned in 1983 to direct Hillel, the Jewish student organization.

“Wolfenson and Irv taught us the difference between an insular Yiddish literacy and placing it in the context of the larger culture,” says Sapoznik, “and they were both concerned about its survival.”

Meanwhile, the study of Yiddish continues on campus. In January 2017, seven academics will be focusing on the language and associated culture, says Simone Schweber, director of the Mosse/Weinstein Center for Jewish Studies. “This year, we welcome two new professors in Yiddish literature and culture: Marina Zilbergerts and Sunny Yudkoff. We are thrilled that 100 years after it first offered Yiddish, UW–Madison will once again become the place to go to study Yiddish language, literature, poetry, film and culture.”

The Mayrent Institute offers a monthly Yiddish conversation group. But Sapoznik, a five-time Grammy-nominated producer, historian and archivist of Yiddish music, has emphasized music. The second World Record Symposium, held last April, attracted “a mashup of people” who work with historic sound recordings, including archivists, musicologists and people from the law school who discussed copyright.

Reissuing, reviving and celebrating Yiddish music and recordings fits squarely within Madison’s on-and-off tradition of Yiddish scholarship, says Sapoznik. “Wolfenson and Irv Saposnik both found creative ways to use the past, to use this language, and the Jewish cultural identity, and they created platforms to move them into the future. We’re trying to do the same thing.”

A ceremony honoring Louis Wolfenson’s many contributions to Jewish life in Wisconsin will be held at 11 a.m. Sunday, Sept. 25, at his grave in Forest Hill Cemetery on Speedway Road in Madison, in Lot 50, Section 10, near Glenway Golf Course.

Tags: arts, history, Jewish studies, language