9/11: 20 years later, campus remembers

Never forget.

Those two words have become synonymous with Sept. 11, 2001.

Twenty years later, we remember where we were and what we were doing when we first heard the news that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. And then another, erasing any temporary thoughts of some sort of freak accident.

Gary Sandefur, then dean of the College of Letters & Science, was interim provost at the time, and had to step in to lead the university when suspended air travel left then-Chancellor John Wiley stranded in Los Angeles.

“Over the course of the week we dealt with the shock, fear and sadness that everyone on campus felt as we dealt with campus safety concerns, the desire to honor those killed, whether to have the football game on Saturday and whether to have a special campus event on Friday as called for by President Bush,” Sandefur recalled on the 10th anniversary of 9/11. “I remember the deep respect to those who lost their lives along with a strong sense of a united, concerned and determined campus community.”

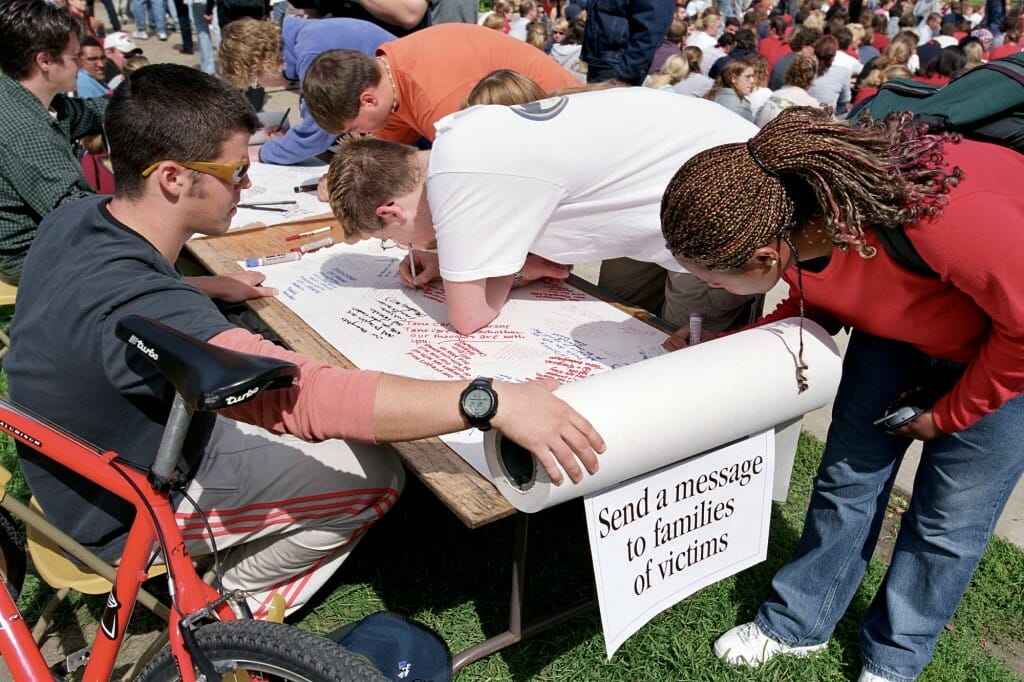

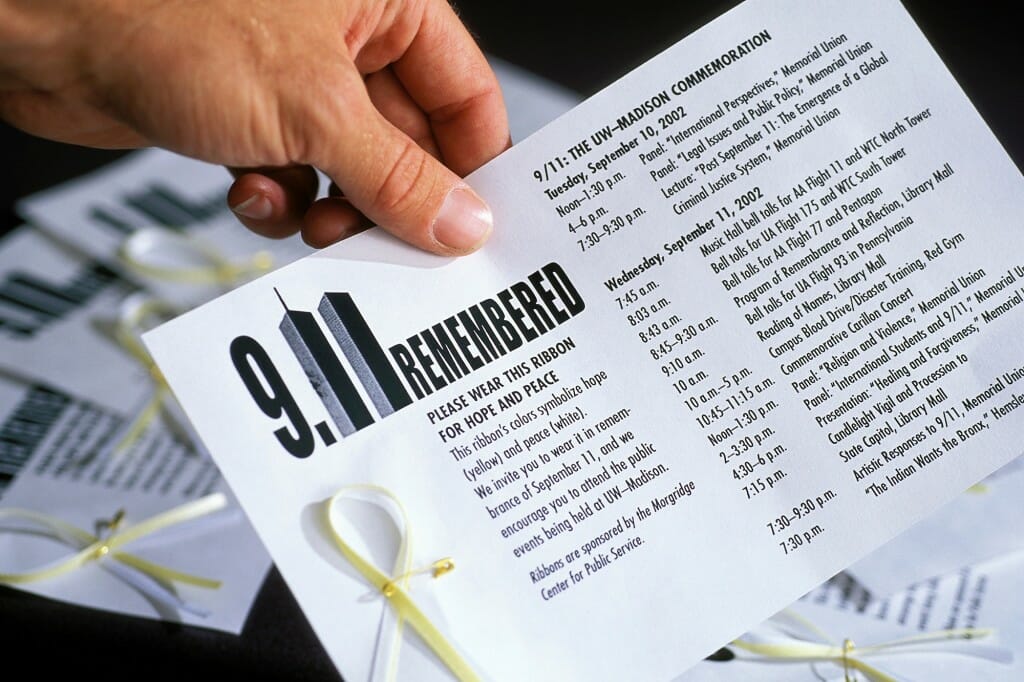

Campus came together in the days that followed with thousands gathering at Library Mall to commemorate those who had died in the attacks and to take some small comfort by being with others as we shared our collective grief.

We weren’t glued to our smartphones – the first iPhone wouldn’t come out until 2007. We were glued to our TVs, often watching in public spaces on campus with others.

Social media was years away. We shared our thoughts in person – and our moments of silence.

The majority of today’s UW–Madison students were either not born yet or far too young to remember that day. But people who were on campus easily remember that horrific day and the confusing days that were ahead. Five of them shared their recollections with us.

Charles L. Cohen

Emeritus professor of history; then, professor of history and director of the Religious Studies Program

Where were you and what were you doing when you found out the news?

I was climbing the steps of the Humanities Building on the way to my office prior to teaching my 9:30 a.m. class.

What do you remember about that day and your reaction?

I remember looking up into a lovely sunny sky and scanning for airplanes. Since I am from New York City and had family in Manhattan, I called my brother to find out how he was, just in (the unlikely) case that he had been downtown. We tried to process what was happening.

Campus held several events and remembrances. Did you attend any? If so, what do you recall?

As director of Religious Studies, I thought that the program should do something to allow people to learn more about Islam, so I organized what (harkening back to my own student days in the 1960s) I called a “teach-in” on Sept. 19 in 3650 Humanities. We had an overflow crowd in the 500+ seat hall. We had a dozen speakers.

Did 9/11 impact your teaching? If so, how?

Not my teaching per se, but my entire career. The event led Milwaukee businessman and benefactor Sheldon Lubar to propose to Chancellor Wiley that UW create an organization dealing with Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Between 2002 and 2005, I negotiated the formation of what became the Lubar Institute for the Study of the Abrahamic Religions, which I led from 2005-2016. Running the institute shifted my focus from early American history, which is what I had originally been hired to teach, to comparative religious history, and culminated in my offering a course on “Braided Histories: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.” I published a book based on the course, The Abrahamic Religions: A Very Short Introduction, with Oxford University Press in 2020. I had been trying to develop Islam academically on campus in the years prior to 9-11, and the event only intensified my efforts. It also gave me a commitment to fighting Islamophobia that continues to the present.

The majority of our students either weren’t born yet or were too young to remember 9/11. What’s one thing you think they should know about that time?

As a historian I would routinely tell my students that we cannot judge the importance of events until we can gain historical perspective; our culture and its media are overly quick to pronounce judgments that in history’s light quite frequently prove at best uninformed, at worst completely wrong. Still, I remember a colleague saying on 9-11 that he could feel history shifting under his feet, and that we were entering a new era. 9-11 was a rare event whose importance was immediately apparent. But how it was (and continues to be) important is an ongoing story. So, if I were still teaching, I would tell my students not to make settled judgments about 9/11 even now.

Diana Hess

Dean of the School of Education, Karen A. Falk Distinguished Chair in Education; then, assistant professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, School of Education

Where were you and what were you doing when you found out the news?

I was at home reading the newspaper. A friend called me and told me to turn on the news.

What do you remember about that day and your reaction?

I remember feeling so concerned for my friends in New York City — and anxiously awaited hearing from them. I also thought immediately about the students in our social studies teacher education program who were student teaching in area middle and high schools. We had class scheduled to start at 5 p.m. that day and I wondered whether to cancel it. But then the students started calling me asking to have class. They did not know how to help their students understand what was happening and wanted help. We spent three hours that night figuring out how the student teachers could address what was happening in ways that were pedagogically sound and helpful, while also dealing forthrightly with students’ concerns and fears.

When did you begin considering doing research into how 9/11 was taught? Why did you pursue this area of research?

The day after 9/11, I started collecting lesson plans about the events that were being developed and disseminated by curriculum organizations and newspapers. It was clear that 9/11 and its aftermath were going to be very important and I was curious about how this would be represented in curriculum and be taught, both in the near term and in the future. The study began in 2001 and is ongoing.

Professor Jeremy Stoddard was a graduate student and he was a member of the original study team. Initially I was the principal investigator when we studied how 9/11 and its aftermath were presented in supplemental curriculum and textbooks. In 2011, he became the principal investigator when we expanded the study to analyzing 9/11 in state standards documents. In 2018 we also created a survey that collected information from social studies teachers to find out how they taught about 9/11 and its aftermath, what materials they used, and what objectives they were trying to accomplish.

How was 9/11 first taught? Has it changed?

Initially it was taught as a current event. Teachers wanted to help students learn about what happened and to whom. The question of why 9/11 happened was much more complicated. I remember teachers really struggling with how to make sure they were not spreading rumors or conspiracy theories, given there was so much uncertainty.

What have you learned since starting that research?

Initially, we were surprised by how quickly 9/11 and its aftermath were included in textbooks — which often lag quite a bit. With a few exceptions, while most of the textbooks we studied focused at least a bit on 9/11, they did not include much detailed information about what happened — as if students would already know those details. And very few included content about some of the controversial policies that were part of the aftermath of 9/11. The recent survey of teachers showed that many teach about 9/11 on the anniversary and they yearn for more high-quality curriculum that focuses on 9/11 and its aftermath.

The majority of our students either weren’t born yet or were too young to remember 9/11. What’s one thing you think they should know about that time? Have you seen any common misconceptions that they may have?

Given how important 9/11 was and its long-term effects, it is impossible to identify just one thing students should know. Broadly, they should understand what happened on 9/11, why, and the aftermath, including, for example, the war on terror, the Patriot Act, the debates about the use of torture, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. There were a wide range of controversial issues surrounding 9/11 and its aftermath that the students should understand and deliberate — especially those that continue to impact the United States and other nations today.

A common misconception is that 9/11 was something horrific that happened on one day. Many students don’t understand the connections between 9/11 and hugely important changes in society.

Jeremy Stoddard

Professor in Curriculum and Instruction, School of Education; then, graduate student at UW and worked as a Curriculum and Technology Professional Development Specialist for CESA 5 – working in 35 school districts in the central part of the state

Where were you and what were you doing when you found out the news?

I worked at the time for CESA (Cooperative Educational Services Agency) 5 out of Portage, Wisconsin, and was on my way to a high school northwest of Madison at the time I heard of the first plane hitting the WTC – which was reported as a small plane. I then saw the events unfold with colleagues at the school I was working at and then with high school students in their school library on a TV.

What do you remember about that day and your reaction?

I think initially confusion and horror like most people. I was with a colleague whose brother was a pilot for American who flew regularly out of Boston – so it was also some tension before she found out if her brother was flying that day – which he was not.

When did you begin considering doing research into how 9/11 was taught? Why did you pursue this area of research?

I started my PhD in the fall of 2002 and worked for Diana Hess on a project focused on curriculum produced for the first anniversary to teach about 9/11 and have collaborated since with her.

How was 9/11 first taught? Has it changed?

We can’t say for sure as we only surveyed teachers in late 2018-19. We know that the themes of 9/11 as an unprecedented and shocking event, with the world coming around the U.S. against terrorism and the heroism of firefighters and first responders – as a kind of collective memory event is still pretty common and was definitely common early on. More of a commemoration of the event and honoring the victims.

We have seen some changes as a result of now having students who have no lived memory of the events and some because younger teachers want their teachers to view it as a significant historical event that has impacted their lives more than as a commemoration or collective memory event.

What have you learned since starting that research?

A lot – in particular the themes of 9/11 have largely stayed the same, but what is included or not included has shifted – some controversial aspects are included in texts and standards, such as the Patriot Act, where as others are included less often (justification for invasion of Iraq, Guantanamo Bay detainees, etc.).

The majority of our students either weren’t born yet or were too young to remember 9/11. What’s one thing you think they should know about that time? Have you seen any common misconceptions that they may have?

Some teachers report misinformation from students – either mis-rememberings from family members to even conspiracy theories they have found online.

I think we should help young people see beyond the collective memory event to also look at the impact on different groups since 9/11 – Muslim Americans, veterans and military contractors, long-term health effects of the people who worked on the WTC site, the many civilians overseas impacted by the War on Terror. I also think we want young people to understand the complexities in the context of 9/11 and the years leading up to it.

Kathleen Bartzen Culver

Associate professor and James E. Burgess Chair in Journalism Ethics, School of Journalism & Mass Communication and director of the Center for Journalism Ethics; then, faculty associate

Where were you and what were you doing when you found out the news?

I was in Vilas Hall. Two colleagues and I had just finished interviewing a job applicant for an adviser position. As we were walking her out, our administrator came urgently down the hall, asking if we knew what happened. We took off running, leaving her behind. I’ve always felt bad about that.

What do you remember about that day and your reaction?

Like everyone else, I remember how vividly beautiful it was outside. One of those absolutely perfect Wisconsin fall days. That particular blue of the sky that we get in September.

A number of us were gathered in a lounge, trying to watch the coverage on an ancient large-screen TV. We were tuned to NBC, which first had the Today Show team on and then Tom Brokaw arrived. I recall being frustrated at the lack of information, so I went to my office and tuned into CBS News radio on an old black boombox I had. They had multiple reporters scrambling on the ground and had far more information than we were getting from TV networks.

I remember listening to a CBS reporter screaming as the first tower fell and staring out my office window at that impossible blue sky, tears streaming down my face.

Beyond that moment, everything about that day is a blur. I don’t have solid memories, just feelings. I cannot for the life of me remember coming home to my husband and kids, but I tear up at thinking about holding them.

Has 9/11 impacted your teaching at all?

One of the hardest parts of that week for me was figuring out what to do with classes. It felt strange to convene them, yet I knew being together and forging ahead could provide a sense of community and strength. I decided to continue but offer excused absences for anyone who wanted them. No one did. I choked up often in lecture in the weeks following and at the end of the semester heard from multiple students who were grateful that my teaching assistants and I tried for the right balance of acknowledging the tragedy but continuing with life. I always question whether I really did strike that balance right.

One of the lasting ways it changed me was confronting how hatred and prejudice can seep into our classrooms. Online media were in their infancy back then, but some of what was out there involved truly awful stereotyping and blame. I talked more about bias and media representations in those months and that’s continued to this day.

The majority of our students either weren’t born yet or were too young to remember 9/11. What’s one thing you think they should know about that time?

That difficult times can bring people together, yet fear can bubble a lot of bad feelings and drive a lot of bad decisions. When you face times like 9/11, you have to actively work against your own fear and turn to your values. It’s the only way forward.

Jon Pevehouse

Professor, political science and public affairs; then, assistant professor

Where were you and what were you doing when you found out the news?

I had jumped in the car to take my dog to the vet. It was the first day off I had for the semester and I turned on the radio.

What do you remember about that day and your reaction?

I was incredibly sad – for the victims, first and foremost. But my mind was spinning thinking how much this was going to change the country and the international system. Those who study international relations knew right away this was going to have incredibly long-term consequences.

Has 9/11 impacted your teaching at all?

Absolutely. The day after the attack I had to teach a course on American foreign policy. I threw the syllabus out for the next month. For the next two class periods, we basically did a Q&A where students could ask questions, express what they were thinking, etc. Since then, I spend a lot more time discussing terrorism, the war on terror, and how it was this structural shift in policymaking.

The majority of our students either weren’t born yet or were too young to remember 9/11. What’s one thing you think they should know about that time?

The tremendous jolt it was to everyone. It was such a surprise, made many people nervous and scared, and everyone had a sense it was going to change so much. I tell students that COVID has changed our lives in political, economic and social ways and those changes have “rolled out” over 18 months. Imagine the prospect of similar changes hitting you in a matter of hours. For many people, that was 9/11.