Tom Brock, who discovered world-changing extremophiles, dies at 94

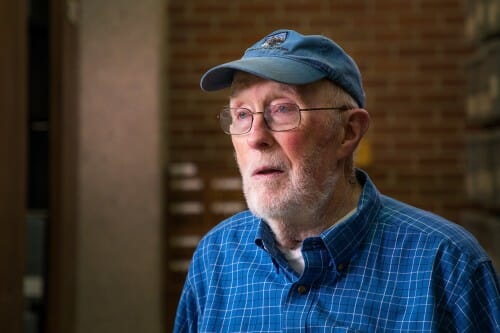

As an ecologist, when Tom Brock first visited Yellowstone National Park in the mid 1960’s, he saw the colorful hot springs in a different way than most. He was stunned by the microbes present there that no one seemed to know anything about. His research that followed uncovered a previously unknown characteristic of life — the ability for bacteria to live in near-boiling water. The existence of these organisms would later lead to groundbreaking discoveries in the fields of microbiology and genetics. 2017 video by Craig Wild/University Communications

Tom Brock, a pioneering microbiologist who redefined the bounds of life, passed away at his home in Madison in April from complications following a fall. He was 94.

Brock spent most of his scientific career at the University of Wisconsin–Madison as the E. B. Fred Professor of Natural Sciences in the Department of Bacteriology. He also chaired the department from 1980 to 1983.

Brock is widely known for opening a new field of biology studying extremophiles — the microorganisms that survive the harshest conditions on Earth. He was the first to discover bacteria growing at nearly boiling temperatures in Yellowstone National Park.

Brock’s students remember him as a tough, but fair, mentor who sharpened their scientific and leadership skills. University Communications

One of the species that he discovered, Thermus aquaticus, helped usher in the modern era of molecular biology by forming the foundation of polymerase chain reaction, PCR. By easily amplifying DNA, PCR allowed the development of widespread DNA sequencing, created a ubiquitous scientific tool, and underpins today’s best tests for the COVID-19 virus.

A prolific writer, Brock authored hundreds of research papers and wrote or edited nearly two dozen books. His textbook, “Biology of Microorganisms,” which he wrote by himself in 1970, is still a mainstay of microbiology courses. It is now in its 16th edition. Not content only to write, Brock and his wife Kathie started Science Tech Publishers, an academic publishing company that operated for 12 years and published dozens of books.

“He had an incredible personality and persona. He was kind of bigger than himself. He was bigger than life,” says Jo Handelsman, director of the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery and a longtime mentee, colleague and friend of Brock’s. “He just strode through life in his own way doing what he believed in. And he had very, very deep and strong beliefs, and I think that’s what I admired about him the most.”

Brock’s work at Yellowstone began while he was a professor at Indiana University. On his first trip out West in 1964, Brock stopped by the park and marveled at the hot springs, which flowed away in colorful streams that gradually cooled. He recognized that despite the harsh conditions, microbes were thriving in the water.

So Brock returned with a research team and some grant money. At the time, scientists believed that life could not flourish above 160 degrees Fahrenheit. But taking samples from around and within the hot springs, Brock and his students discovered life growing in superhot streams and even in boiling pools of water.

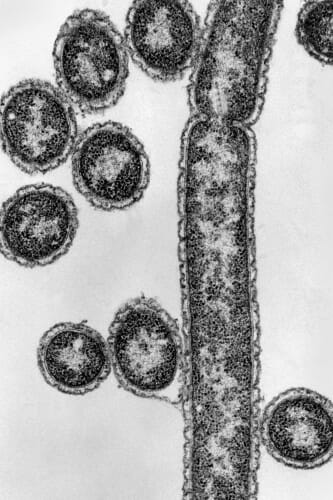

In 1969, Brock and undergraduate student Hudson Freeze published their discovery of Thermus aquaticus, which they found thriving in temperatures up to 170 degrees Fahrenheit. They named the bacterium after the hot water it called home.

Thermus aquaticus bacteria discovered by Brock redefined the bounds of life and influenced studies of the origin of life on Earth and on other worlds. UW–Madison

Brock’s discovery of these organisms cracked open a new field of study in biology. Extremophiles, as these hardy microbes became known due to their ability to survive extreme conditions, have been found buried in deep mines, clinging to superhot vents at the bottom of the ocean, and encased in ice. They redefined the bounds of life and influenced studies of the origin of life on Earth and on other worlds.

Some extremophiles turned out to belong to the Archaea, an entirely new branch of life that completely changed our understanding of the evolution of complex organisms.

Years later, the scientists developing PCR turned to the heat-resistant DNA-copying enzyme from Thermus aquaticus. To work, PCR requires near-boiling temperatures, and the resilient enzyme perfected the technique. Modern biology — from basic research through to personalized medicine and disease diagnostics — would be impossible without PCR.

Brock and Freeze’s discovery earned them the 2013 Golden Goose Award in recognition of the world-changing, but unpredictable, power of curiosity-driven basic research. During the COVID-19 pandemic, National Geographic and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel profiled Brock for his contributions to tracking the disease with PCR-based tests.

Brock and Kathie, also a microbiologist, met while she was a postdoctoral researcher on his Yellowstone team. They married in 1971, the same year Brock moved to UW–Madison, where Kathie also taught. He continued his Yellowstone work for a number of years but eventually turned his eye to his new backyard: Lake Mendota.

“When we came to Wisconsin, Tom made a conscious decision that going to Yellowstone was valuable, but because the taxpayers of Wisconsin were paying him, he felt an obligation to work on — and was also interested in — the lakes of Wisconsin,” says Kathie.

Unlike the simplified, if extreme, environments in Yellowstone, Lake Mendota was teeming with a complex ecosystem of microbes, plankton and fish. Brock analyzed research on the microbial cycling of nutrients in the lake from the 1920s and wrote the 1985 book “A Eutrophic Lake: Lake Mendota, Wisconsin,” which compared that early work with fresh data from his lab.

In 1981, Brock helped found the North Temperate Lakes Long-Term Ecological Research Network. The NTL-LTER, a unique way to fund research over decades, continues to this day, housed at the UW–Madison Center for Limnology.

On Aug. 20. 2013, Tom and Kathie Brock enjoy the fruits of their labor: 140 acres of restored prairie, oak savannah and woodlands that they established as the Pleasant Valley Conservancy in Black Earth, Wisconsin. Photo: Jeff Miller

“Tom was a remarkably accomplished human being — great scientist for work in environmental microbiology, great conservationist for restoring the health of the land, and a natural teacher and great human being,” says Steve Carpenter, former director of the Center for Limnology.

Brock’s students remember him as a tough, but fair, mentor who sharpened their scientific and leadership skills. He trained over 30 doctoral students and 18 postdoctoral researchers.

“One thing I inherited (from Tom) is the way of directing students, in that you are not on top of them all the time, but if they need you, you are always available. This kind of freedom, and at the same time support, is something I have been using ever since,” says Carlos Pedrós-Alió, a professor at the National Center for Biotechnology in Barcelona, Spain, who earned his doctorate under Brock studying Lake Mendota’s microbes.

Cornell University microbiologist Steve Zinder also earned his doctorate working with Brock. He worked in Yellowstone during the lab’s last research expedition at the park before turning his attention to the sulfur cycle in Lake Mendota.

“He had a way of pushing things ahead and asking simple questions, which yielded results better than getting lost in the weeds,” says Zinder. “Tom loved what he did. He loved working. He loved learning things. He loved telling people about things.”

After his retirement from the university in 1990, Tom and Kathie set to restoring a 140-acre tract of land in the Driftless Area of Wisconsin to prairie and oak savanna. Pleasant Valley Conservancy was dedicated a State Natural Area in 2008. Always the writer, Brock wrote a two-volume history of their endeavor.

UW–Madison awarded Brock an honorary doctorate in 2019 for his contributions to science and his decades of conservation work.

Brock receives an honorary doctorate for his accomplishments in science and conservation. Photo: Jeff Miller

His daughter Emily recalls countless hobbies her father mastered throughout his life, from piano to opera to canoeing. “He never rested on his laurels. He was always interested in starting an entirely new project and becoming a beginner again,” she says.

Common to Brock’s largest ventures — Yellowstone, Lake Mendota, publishing, land restoration — was his boundless curiosity and preternatural ability to follow that curiosity where it led, says his son Brian.

“Yellowstone really was a lark, like ‘Let’s go look at these hot springs for fun.’ And what starts as intellectual enjoyment becomes a full-blown project,” he says. “It blossoms from there.”

A celebration of Tom Brock’s life is being planned for summer or fall. Memorial contributions can be made to the charity he and Kathie founded to fund and manage their ecological restoration work at Pleasant Valley Conservancy: Savanna Oak Foundation Inc., c/o The Prairie Enthusiasts, P.O. Box 824, Viroqua, WI 54665.

Tags: environment, microbiology, obituaries, research