Unimaginable loss, unimaginable resilience: Remembering the pandemic of 1918

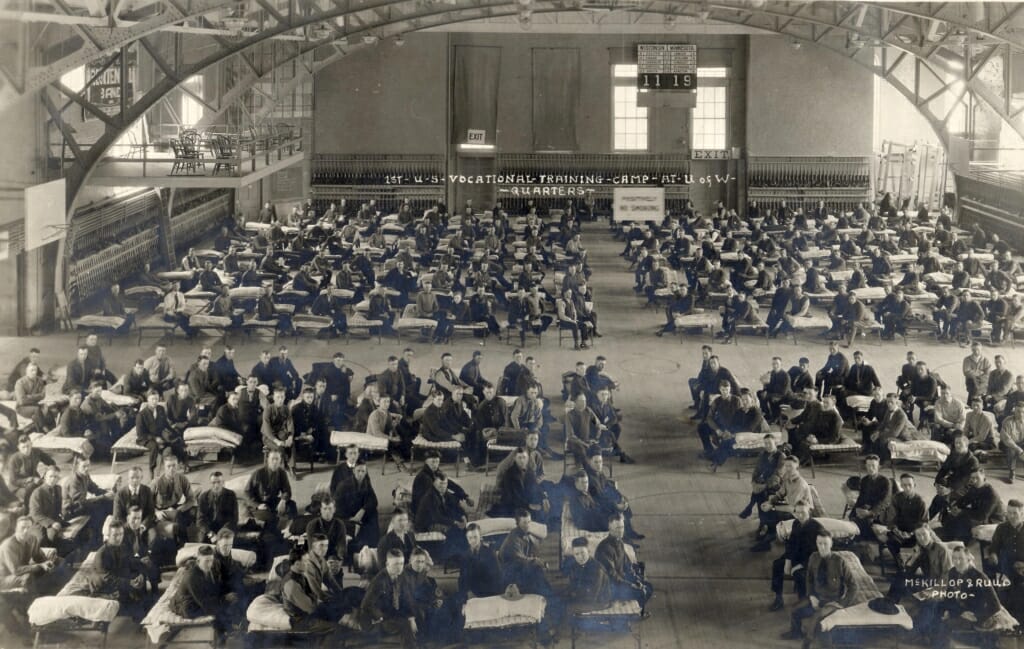

Student soldiers quartered on cots at a Vocational Training Camp for army recruits in the Armory (now known as the Red Gym). “We needed young men to go to Europe. We weren’t going to tell them people were dying in Europe from the flu,” curator Micaela Sullivan-Fowler says. UW–Madison Archives

The enemy was invisible, quietly creeping into homes, schools and battlefields.

Troops had trained for war but no one knew the danger following their every move, threatening not only their own lives but those around them.

The 1918 influenza epidemic during World War I killed an estimated 50 million worldwide, including more than 675,000 Americans.

One-third of the planet was infected, an estimated 500 million people. The life expectancy in the United States dropped from 51 years to 39 — what it had been in 1868.

The enormity of loss is hard to comprehend. The numbers are too big, the tragedy too immense.

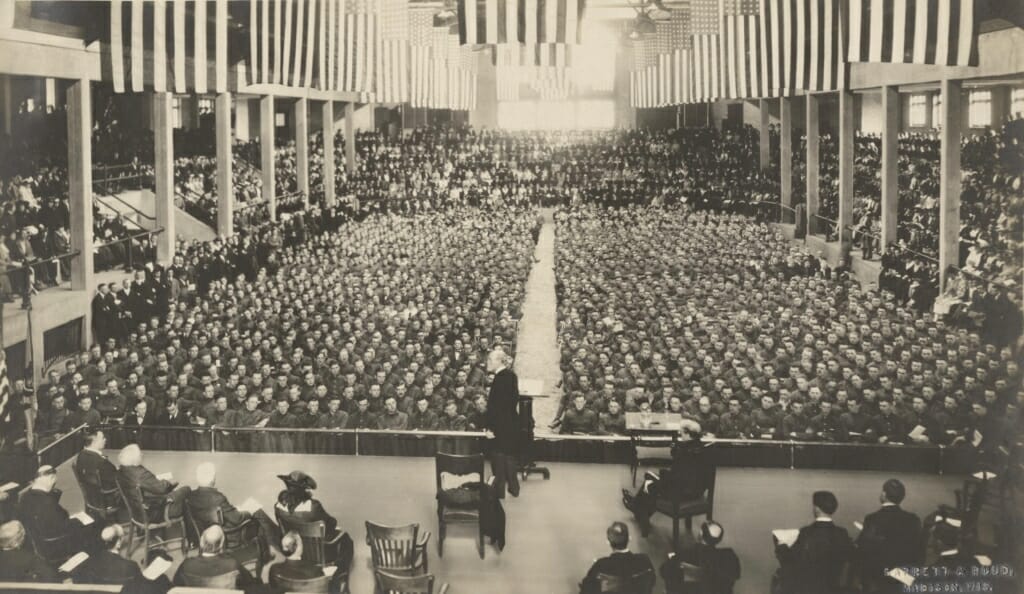

Student Army Training Corps (SATC) recruits are inducted on Library Mall in 1918. They participated in military drills as well as classes. UW–Madison Archives

“The University went through two severe epidemics of influenza; the first in 1918, involving nearly 1,600 cases (besides those in Section B of the Student Army Training Corps) and 48 deaths; the second in 1920 with over 1,600 cases but only 11 deaths,” UW President Edward A. Birge told the Board of Regents. “No similar epidemics either in their extent or in the number of fatal cases, have ever been recorded in the history of the university and it may be hoped that there will be no recurrence of such calamities.”

Now comes COVID-19. While there are some similarities to 1918, there’s one big difference. In 2020, we can look back and see what people are collectively capable of surviving despite loss all around them.

“The impact on our community was unprecedented in 1918,” says Micaela Sullivan-Fowler, curator and history of the health sciences librarian for UW’s Ebling Library for the Health Sciences. “No matter what goes on, UW rallies. We did it then and we’ll do it this time.”

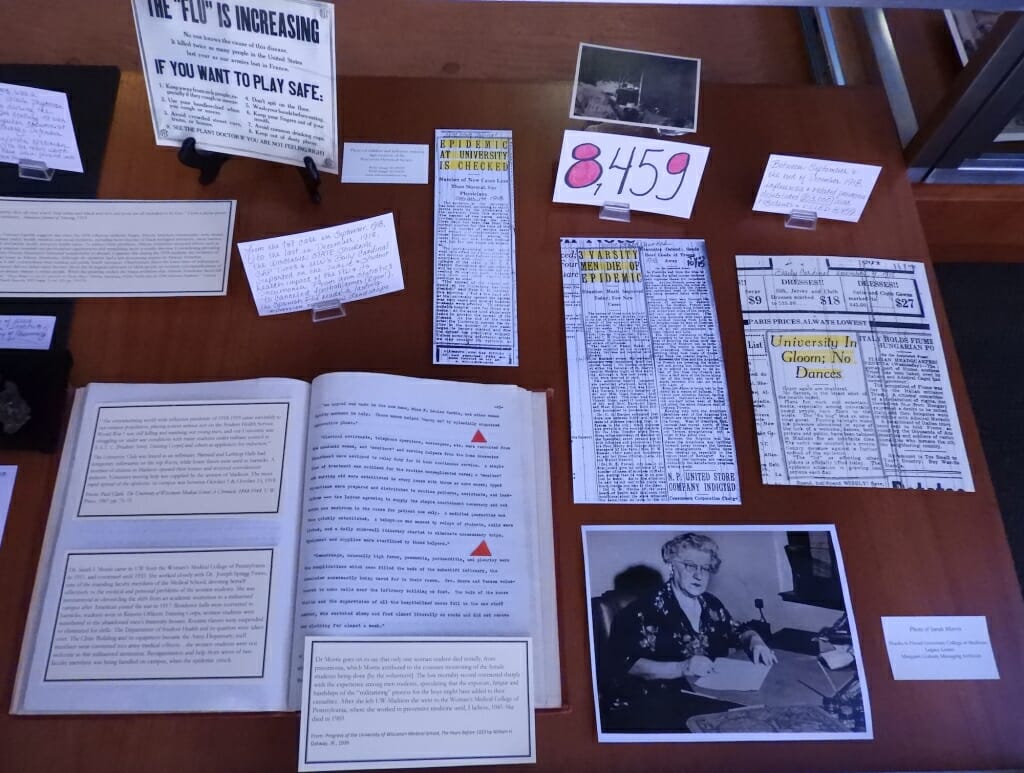

Sullivan-Fowler, also a public historian, has created numerous exhibitions over the years on wide-ranging topics like the histories of human experimentation, maritime medicine, radiation and the bomb, and Civil War medicine. She wanted to recognize the 100th anniversary of World War I and the pandemic. She dug into the robust book and journal collections at Ebling as well as the UW Archives. The result was “Staggering Losses: World War 1 & the Influenza Pandemic of 1918,” an exhibition at Ebling Library intended to honor the millions who died by recognizing a few. (It’s currently on hiatus due to COVID-19.)

Micaela Sullivan-Fowler dug into the robust book and journal collections at the Ebling Library for the Health Sciences as well as the UW Archives to produce the exhibit “Staggering Losses: World War 1 & the Influenza Pandemic of 1918.” Photo by Jenie Gao

For Sullivan-Fowler, one of the unexpected responses to the exhibition was the emotional outpouring from visitors whose family members had died in Wisconsin in 1918. Grandmothers, grandfathers, uncles, aunts — people they had not reflected on in decades, people whose deaths impacted the trajectory of their family. The power of finding a reminder in an exhibition 100 years later resonated in their comments written in the exhibition guest book. Sullivan-Fowler remembers thinking, “If this ever happens again, we need to do everything we can to avoid these epic losses.” She had no idea how prophetic that concern would become.

“I always wondered why it wasn’t more in the public memory,” she says. “World War I took precedence.”

The United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, fighting alongside Britain, France and Russia. While the flu’s possible origins are debated even now, the first case was reported at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 4, 1918.

As the virus spread quickly, warnings about it didn’t.

“We needed young men to go to Europe. We weren’t going to tell them people were dying in Europe from the flu,” Sullivan-Fowler says.

UW President Charles Van Hise speaks in April 1917 at the War Convocation in the Stock Pavilion marking the U.S. entrance into World War I, with all the Cadet Corps in attendance. UW–Madison Archives

Information was withheld by countries involved in the war. Spain remained neutral and was open with its citizens about the danger. And just like that, the disease became known as “the Spanish flu.”

Even in 1918, flu wasn’t new to people. Why make such a big deal out of this one? It happened every year. But this flu was different. While the flu often preyed upon the old and immunocomprimised, this new flu went after young, healthy men.

There was no vaccine, no antibiotics. And at the time, no one knew what caused it. Many thought it was bacterial.

“The reason it transmitted so alarmingly and dramatically was because of those troops. There would be 1,000 to 3,000 men on ships and in camps,” says Sullivan-Fowler.

In early 1918, the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) came to UW’s campus, resulting in students participating in various military drills as well as classes.

Rumors of Spanish flu among them were quickly shot down.

“No Influenza at University Camp,” read a Wisconsin State Journal headline on Sept. 27. But a small number of influenza cases had been seen among SATC vocational students.

“When college opens in the fall, we always have had a number of ‘grippy’ colds among the students,” Dean Charles Bardeen of the Medical School wrote to President Birge.

The university unveils the World War I service flag on Bascom Hall. The United States entered the war on April 6, 1917. UW–Madison Archives

“The epidemic of whatever-it-is at the university is being checked,” an Oct. 7 news article reported. “This morning Major McCaskey went thru the University Club, now being used as S.A.T.C. infirmary. After his visit he caused 80 men to be sent back to their quarters, with the approval of medical authorities. ‘No men capable of eating the hearty breakfasts these men did are fit subjects for the infirmary,’ he declared.”

“There have not only been no deaths here, but there have been no students ill enough to make the medical staff even fear death,” Bardeen said on Oct. 8.

Soon, the epidemic became impossible to deny.

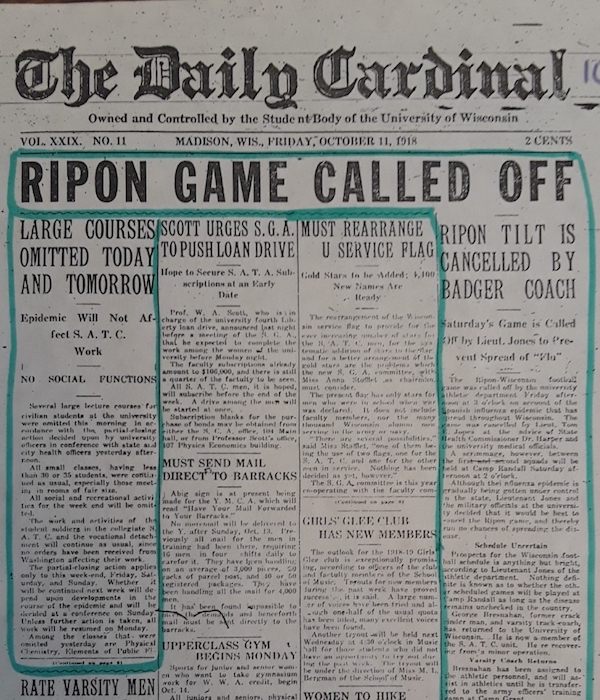

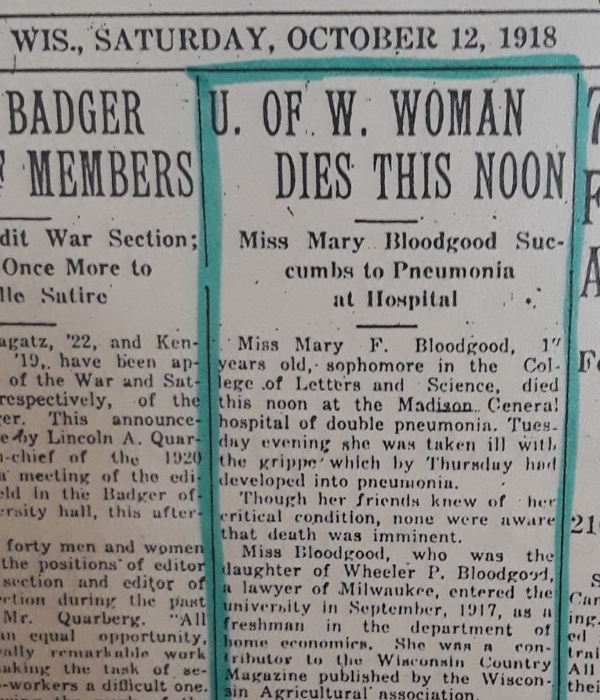

On Oct. 9, Private Arthur O. Ness died — the first student at UW–Madison to succumb to the flu.

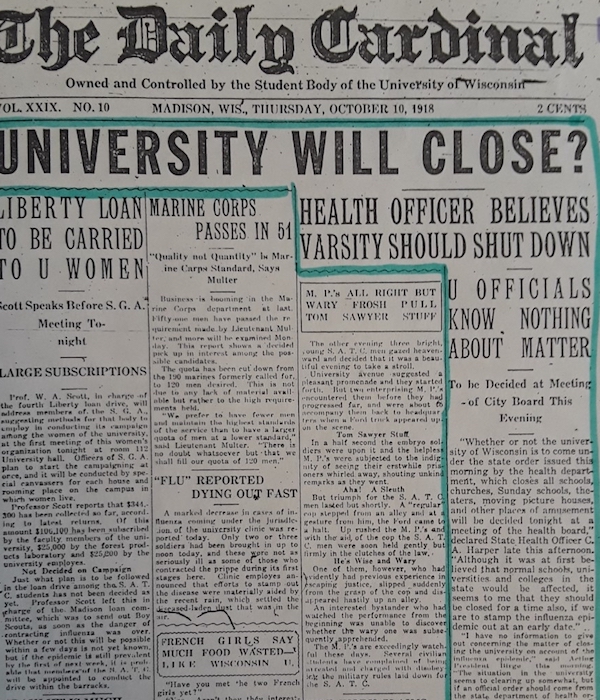

On Oct. 10, state health officer Dr. Cornelius Harper issued a general order closing all public gathering places, including theaters, movie houses, saloons, schools and churches throughout the state.

By mid-October, 5,000 cases in Madison were reported, a massive number considering Madison’s population was 37,000 and Dane County’s 88,000.

During one 48-hour period, there were 175 cases of influenza on campus. The war left campus short-staffed for health care. It was all healthy hands on deck.

“Clerical assistants, telephone operators, messengers, etc. were recruited from the academic women, and ‘monitors’ and nursing helpers from the Home Economics Department were assigned to relay duty for 24-hour continuous service,” wrote Dr. Sarah Morris, who helped organize health care on campus, in a letter. “A simple line of treatment was outlined for the routine uncomplicated cases; a ‘monitor’ and nursing aid were established in every house with three or more cases; typed directions were prepared and distributed to routine patients, assistants, and landladies — the latter agreeing to supply the simple nourishment necessary and set aside one washroom in the house for patient use only. A modified quarantine was thus quickly established. A telephone was manned by relays of students, calls were listed, and a daily sick-call itinerary charted to eliminate unnecessary trips. Equipment and supplies were sterilized by these helpers.”

Picture after picture shows Student Army Training Corps members in tight quarters on campus.

“At the time of the 1918 flu epidemic, I was a student at the University of Wisconsin and developed influenza myself, after seeing many acquaintances in the barracks of the SATC affected with many deaths,” wrote Dr. Warner Bump of Rhinelander. “I was ill for about three weeks and out of class for that length of time. Death came to one whole family of my acquaintance — father, mother, and two children. Influenza that year was no respecter of age. Young, vigorous people succumbed just as well as the old people.”

“At the time of the 1918 flu epidemic, I was a student at the University of Wisconsin and developed influenza myself, after seeing many acquaintances in the barracks of the SATC affected with many deaths,” wrote Dr. Warner Bump of Rhinelander. UW–Madison Archives

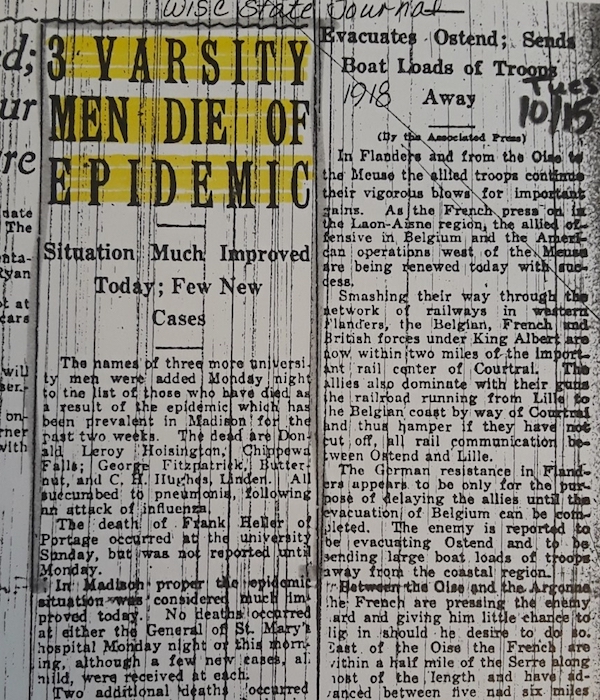

“University in gloom; no dances,” a headline in the Daily Cardinal declared on Nov. 7, 1918.

“Hopes again are shattered. No dances, is the latest edict of the health board,” the story said. “Plans for weekend entertainments, especially among university young people, have flown to the winds. The ‘flu bug’ was an uninvited guest. Fearing that he might make his presence obnoxious in spite of the lack of a welcome, dances, both private and public, have been tabooed in Madison for an indefinite time.”

Campus did not close, although events were canceled as well as classes with more than 35 students. The SATC kept on with its drills.

Dr. Karver L. Puestow, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin Medical School, recalled many details of the flu epidemic. He wrote:

“In 1918 as a medical student at the University of Wisconsin, I was inducted into the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). We were in uniform, lived in barracks, and assigned to classes while getting boot training. Our studies suffered. When in the fall of 1918 influenza struck the campus hard, the University Club at the corner of North Murray and State Streets was taken over as an infirmary. I was assigned to this facility as an orderly or aide to the nurses. It seems that the epidemic struck fast and hard over a short period of time. There was much ado, confusion, frustration, and helplessness. The rooms in the ‘Infirmary’ were divided by suspended curtains presumably to try to effect as much isolation as possible. Treatment was in the nature of nursing care. The force of workers was largely volunteers and our functions as orderlies were usually outside of the cubicles and in carrying out the dead.”

“Clerical assistants, telephone operators, messengers, etc. were recruited from the academic women, and ‘monitors’ and nursing helpers from the Home Economics Department were assigned to relay duty for 24-hour continuous service,” wrote Dr. Sarah Morris.

For all the information available about the influenza epidemic of 1918, it is difficult to find much about what it was like for students on campus at the time. How much did they know? How did they cope? What were they thinking?

“I wonder if students at that time were nearly numb with the prospect of loss, constant loss — they had been experiencing the war for nearly four years,” Sullivan-Fowler says. “Perhaps the flu was just one more unfortunate reality.”

A poem published in The Capital Times Oct. 23 gives a glimpse:

“Classes have been closed on account of the ‘flu’

And we poor students haven’t known what to do,

We’ve telegraphed our parents, as good children should,

And said not to worry – it would do no good.

We’ve wished more than once, that we were in S.A.T.C.

Because it would seem they are as immune as can be

They go to their classes just the same as ever,

While we with the world our relations must sever.

We eat and we sleep as we have been advised

And still our wishes are not realized.

The Candy Shop’s closed, and movie too.

So what in the world are we going to do,

On Friday and Saturday of each week

With classes over and recreation we seek!

With the end of the ‘flu’ we can our pleasures renew

So fight the ‘flu’ and give the Devil his due.”

“Still,” Sullivan-Fowler adds, “we lost nearly 80 students to the war and to influenza, and with a student body of 4,000, surely everyone knew of someone who had died. Surely there was some sort of collective or individual feeling of grief among the student body.”

The “Staggering Losses: World War 1 & the Influenza Pandemic of 1918” exhibit at Ebling Library is currently on hiatus due to COVID-19. Photo by Amanda Lambert

More than 100 years later, we know the importance of capturing people’s stories. The University of Wisconsin–Madison Archives is collecting digital journal and diary entries, emails, photographs, videos, voice memos and audio recordings, digital art, and other digital documentation of how our campus community has been affected by the coronavirus pandemic. The Madison Public Library and Wisconsin Historical Society are also collecting stories to document people’s experiences.

Today’s students are more likely to text than telegraph their parents but the sentiment of loss is very much the same, now and then.

“Anything that wasn’t war-related or flu-related like a dance was incredibly dear to their hearts. The attainment of normalcy, like now, but certainly heightened with the war, was what they hoped for,” Sullivan-Fowler says. “Did they wear their masks? Wash their hands? I have a feeling they are like the young people of today … just wanting to get on with their studies and their lives.”

In 2020, we know others survived the pandemic of 1918, although not without unimaginable loss. But this time, we can look back and find tangible hope in the resilience shown at that time.