Sifting and winnowing turns 125: The tumultuous story of three little words

Farmers know all about sifting and winnowing.

First you sift by loosening the chaff — the seed heads and straw — from the edible grain. Then you winnow, removing the loosened chaff from the grain, often by throwing it in the air. The heaviest grain falls to the earth, waiting to be consumed.

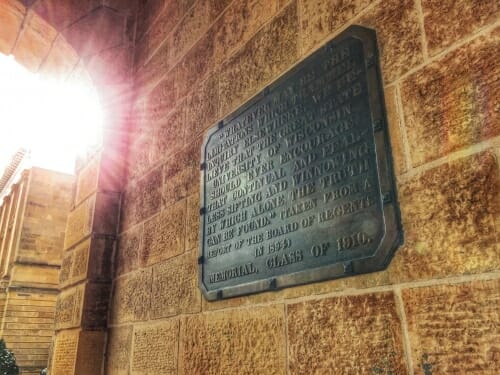

Sifting and winnowing has a special meaning at UW–Madison. Perhaps you’ve seen the plaque at the entrance of Bascom Hall:

The Board of Regents’ articulation of the UW tradition of “sifting and winnowing” is memorialized on a plaque outside the entrance to Bascom Hall. UW–Madison photo

“Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere, we believe that the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”

Those words were first shared on Sept. 18, 1894, by the UW Board of Regents in defense of a professor named Richard Ely. But why? How did an agricultural phrase come to symbolize academic freedom? What follows is the truth, sifted and winnowed from the archives.

From farmer to economist

Richard Theodore Ely was born April 13, 1854, in Ripley, New York. His father was a devout Presbyterian and struggling farmer. While his land was well-suited to grow hops, he refused. Hops were used for beer, after all.

Ely gained a strong work ethic but left the farm to pursue an education. In 1876, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Columbia College in New York City. A $500 fellowship allowed him to study abroad in Germany for three years. He received a doctorate in philosophy and economics from Heidelberg University in 1879, graduating summa cum laude.

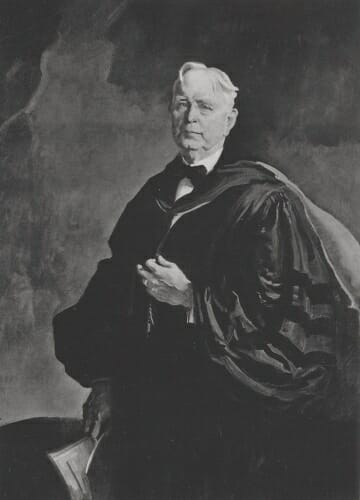

“If I am slaughtered, others in Universities will perish, and what will become of free speech, I do not know,” Ely said. UW Archives

He taught at Johns Hopkins University from 1881 to 1892, developing a reputation as one of the nation’s most distinguished economists. In 1892, he moved to the University of Wisconsin, becoming director of the School of Economics, Politics, and History. Ely set out to make his department not only an important teaching and research center, but also to serve various organizations and groups outside Madison.

“The College Anarchist”

While Ely was applauded by many for his progressive views and interest in social reforms and organized labor, not everyone was a fan. Oliver E. Wells, the Wisconsin Superintendent of Public Instruction and an ex-officio member of the Board of Regents, had heard rumblings of Ely encouraging unions. He read Ely’s book, “Socialism: An Examination of Its Nature, Its Strength and Its Weakness, with Suggestions for Social Reform.” This, Wells resolved, would not stand.

Wells complained about Ely’s “diabolical practices and teachings” to the regents and university President Charles Kendall Adams.

Not satisfied with their response, Wells found a sympathetic ear in The Nation magazine.

In a piece titled “The College Anarchist,” Wells wrote of Ely’s books: “They abound in sanctimonious and pious cant, pander to the prohibitionist, and ostentatiously sympathize with all who are in distress. So manifest an appeal to the religious, the moral, and the unfortunate, with promise of help to all insures at the outset a large public. Only the careful student will discover their utopian, impracticable and pernicious doctrines, but their general acceptance would furnish a seeming moral justification of attack on life and property such as this country has already become too familiar with.”

The letter was also printed in the New York Post with media coverage questioning what was going on in Wisconsin. The regents were forced to address the accusations and launched an inquiry.

The hearing

A trial on Wells’ charges — encouraging strikes and boycotts and teaching students socialism and other “vicious theories” — was held from Aug. 20 to 23, 1894. Ely denied all of the charges.

About 200 people attended each day of the hearings, most siding with Ely. He had the backing of prominent economists, historians and educators. E. Benjamin Andrews, president of Brown University, wrote that Ely was America’s most influential teacher of political economy. “For your noble university to depose him,” declared Andrews, “would be a great blow at freedom of university teaching in general and at the development of political economy in particular.”

While contemplating his own fate, Ely pondered the impact for other academics.

“If I am slaughtered, others in Universities will perish, and what will become of free speech, I do not know,” Ely said.

Sifting and winnowing

Ely need not have worried. The regents cleared him unanimously. Not only was he exonerated; they used the trial to make a much bigger statement. On Sept. 18, 1894, they submitted their report, written by President Adams:

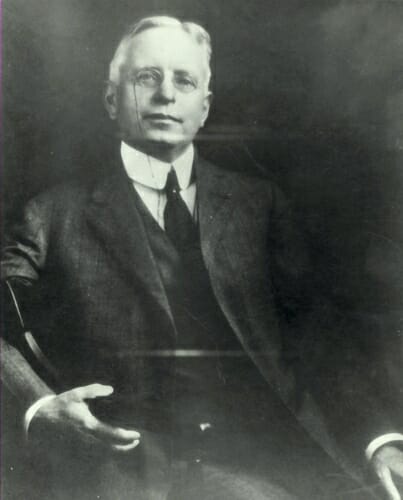

Charles Kendall Adams is credited with writing the words that were excerpted on the “sifting and winnowing” plaque. UW Archives

“As Regents of a university with over a hundred instructors supported by nearly two millions of people who hold a vast diversity of views regarding the great questions which at present agitate the human mind, we could not for a moment think of recommending the dismissal or even the criticism of a teacher even if some of his opinions should, in some quarters, be regarded as visionary. Such a course would be equivalent to saying that no professor should teach anything which is not accepted by everybody as true. This would cut our curriculum down to very small proportions. We cannot for a moment believe that knowledge has reached its final goal, or that the present condition of society is perfect. We must therefore welcome from our teachers such discussions as shall suggest the means and prepare the way by which knowledge may be extended, present evils be removed and others prevented. We feel that we would be unworthy of the position we hold if we did not believe in progress in all departments of knowledge. In all lines of academic investigation it is of the utmost importance that the investigator should be absolutely free to follow the indications of truth wherever they may lead. Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere we believe that the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”

Universities applauded the victory, not only for Ely but for academic freedom.

Fighting words

However profound, “sifting and winnowing” could have easily become a footnote in UW–Madison’s history. But in 1910, another professor found himself under scrutiny.

Emma Goldman, known as “the high priestess of anarchy,” was in Madison. Edward Alsworth Ross, a UW sociology professor, learned that posters announcing her lecture were being torn down.

“Now I take no stock in philosophical anarchism, but I do believe in the principle of free speech,” he said during the middle of a lecture. “For this reason and no other I wish to state to you that Miss Goldman speaks this evening at eight o’clock in the Knights of Pythias Hall.”

This earned Ross a censure from the Board of Regents.

Ely’s name will always be associated with academic freedom. He referred to the sifting and winnowing statement as “the Wisconsin Magna Carta.”

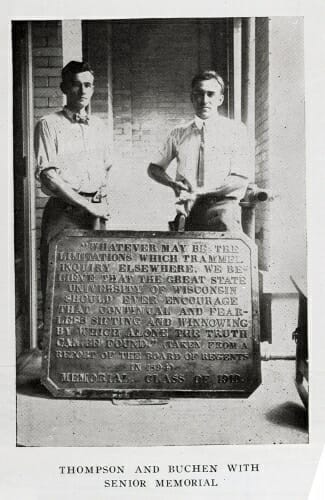

The 1910 senior class had already been meeting to discuss plans for a memorial for its class. And what a memorial it would turn out to be. Theodore Herfurth details the story in “Sifting and Winnowing: A Chapter in the History of Academic Freedom at the University of Wisconsin.”

Lincoln Steffens, known as a “muckraking” journalist, happened to be on campus and suggested to Fred MacKenzie, managing editor of La Follette’s Magazine, that the quote about sifting and winnowing be used for the class memorial to rededicate the regents to the 1894 principle. Steffens expressed regret that it had never been adequately publicized and preserved.

MacKenzie mentioned the suggestion to James Thompson, a senior on the memorial committee.

“(MacKenzie) cautioned me against revealing too much of the source (Steffens) of the subject for fear that political discussion or argument might hamper the execution,” Thompson said.

Thompson shared the idea with the committee but kept the source to himself. The quote was embraced and work on the memorial began. Hugo Hering, chairman of the memorial committee, explained years later that it was the work of an amateur — himself — pointing out the uneven lines of the finished product.

The senior class of 1910 had the memorial plaque cast, but it wasn’t until 1915 that it found its home at the entrance to Bascom Hall. Photo: UW Archives

“I personally prepared the pattern of the Tablet for casting. It was purely a hand-made job, in which I used a three-ply wood veneer panel as a background,” Hering said. “I bought white metal letters, such as used by Pattern Makers, and fastened these letters to the veneer back. Each letter had prongs on the reverse side, and after being properly aligned, was hammered down into the wood. I carted the pattern to the Madison Brass Foundry, and Henry Vogts made the casting, at a cost of $25.00.”

The regents rejected the plaque, saying the students had been influenced by radicals and that they couldn’t allow each graduating class the “privilege of prescribing the character and the placement of its memorial gift.” Commencement came and went. The plaque moldered in the basement of the Administration Building (now Bascom Hall). But the Class of 1910 did not forget. They resumed their campaign in time for their five-year reunion. And they weren’t subtle.

Printed placards appeared on Madison street cars:

Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere, we believe that the great state UNIVERSITY of WISCONSIN should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the TRUTH can be found.

This is the legend on a handsome bronze tablet—the Memorial of the Class of 1910. The Regents have never granted this tablet a place on the campus. If they will finally consent we will dedicate our Memorial at Wisconsin’s greatest Reunion.

1910 COMING BACK—500 STRONG!

The class had the support of the Wisconsin State Journal: “Why has (the plaque) been set up against a cellar wall? What is there in this declaration that can embarrass this University in the light of day? … Let the Regents answer.”

More back and forth ensued. At long last, the plaque came out of the basement and was hung at the entrance of Bascom Hall.

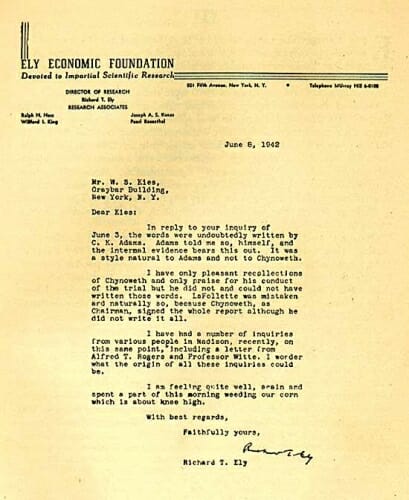

As questions arose about who actually wrote the “sifting and winnowing” words, Ely adamantly asserted that it was former UW President Charles Kendall Adams and not Herbert W. Chynoweth, who chaired the Ely inquiry panel. UW Archives

In 1942 ex-Regent C.P. Cary, who had participated in the 1910 decision, recalled the controversy:

“No single Regent was opposed to the wording or sentiment of the plaque — except the gratuitous fling in the opening sentence at other institutions that might be cramped in their instruction — but they were opposed to being slapped in the face without occasion for it,” Cary said. “It was the entire situation and spirit of it all that was resented. The spirit as the Regents interpreted it was something like this: There, dern ye, take that dose and swallow it. You don’t dare refuse it even if it gags you, and it probably will.”

The legacy

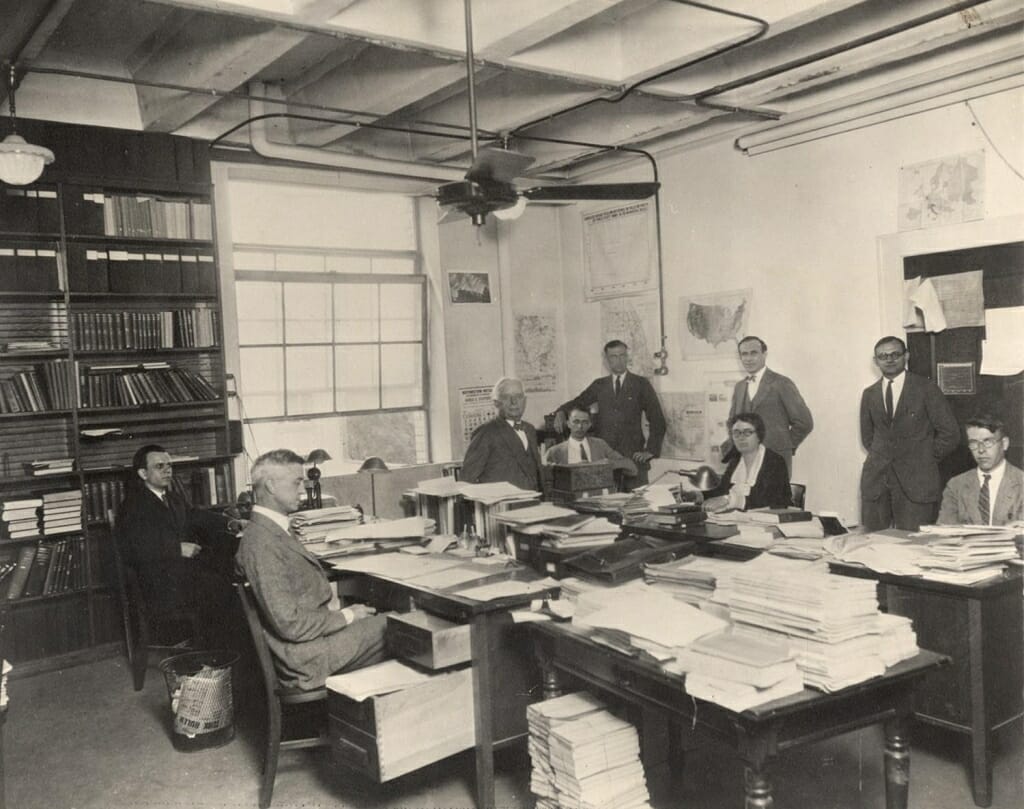

Ely remained at the UW until 1925, when he left to teach at Northwestern University. His academic reputation and influence persists; he’s known as the “Father of Land Economics.” His name will also always be associated with academic freedom. Ely referred to the sifting and winnowing statement as “the Wisconsin Magna Carta.”

Institute for Research in Land Economics and Public Utilities staff, circa 1925, in Sterling Hall. Ely is third from left. Photo: UW Archives

His story was featured in 1964 on NBC’s historical anthology TV series “Profiles in Courage,” based on John F. Kennedy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book. In recent years, economists and others have taken a more critical look at Ely’s legacy, including his support for racist and anti-democratic views.

In 1994, the Board of Regents and the university marked the centennial of the trial with a rededication of the plaque and a conference on academic freedom.

At that conference, UW–Madison Professor of Oncology Waclaw Szybalski spoke about what those words meant to him. Before emigrating from Poland in 1949, he was told by officials that he would be sent to Siberia if he continued his controversial research.

“Why is this ‘sifting and winnowing’ statement so important? Because it so clearly and poetically states the principle of the freedom to teach and research, because it is unique, because it stresses that the University of Wisconsin will not be swayed by temporary vogues or political trends, even if they should prevail at other institutions, and because this declaration is expressed in such beautiful and moving language,” Szybalski said.

“Maybe I am an incorrigible idealist and romantic, even at my age, but each time I read it, I feel a tingle go down my spine and I feel somewhat emotional, I am embarrassed to admit. I am certainly a devotee of this plaque, and I walk all my visitors and collaborators to Bascom Hill, to let them read it and be inspired.”

Tags: Board of Regents, economics, faculty, history