Equine encephalitis detection highlights need to protect horses, people

The first detection of Eastern equine encephalitis in Wisconsin in 2019 was announced last week by the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture and Consumer Protection. A 22-year-old quarter horse mare from Barron County was euthanized after showing symptoms of brain disease.

Although it is quite rare, Eastern equine encephalitis, or EEE, can cause fatal infections and a broad range of serious but nonspecific neurological symptoms in horses and people. It is transmitted mostly by mosquitoes.

The virus was confirmed July 31 at the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, says lab director Keith Poulsen. “Our analysis showed that EEE was present, based on detecting viral nucleic acid in brain tissue.”

Keith Poulsen

In horses, EEE is fatal in more than 90 percent of cases. Although it can be prevented by vaccination, the diseased horse in Barron County had not been vaccinated. “Unfortunately, there is no treatment for this infection,” says Ailam Lim, section chief of virology at the laboratory. “Often, even before a lab diagnosis is complete, the animal must be euthanized since it is so weak and the chance of survival is so low. Those few that survive will have symptoms and neurological signs.”

“The clinical signs in horses can include fever, lethargy, not eating, not being themselves, acting weirdly, walking aimlessly, losing a sense of where they are,” says Fernando J. Marqués, clinical associate professor at the UW–Madison School of Veterinary Medicine. “There may be lethargy or depression. There is a range of severity. Some seem completely out of their minds, crazy.”

Protection against EEE is a “core vaccine in equine veterinary medicine,” Marqués says.

Human cases of neuroinvasive disease caused by EEE virus, 2009-2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Because the symptoms of brain infection can overlap with West Nile virus and equine herpesvirus 1 infection, a diagnosis of EEE is confirmed by genetic testing of brain tissue to evaluate the presence of the virus, says Lim. Although genetic sequencing can also confirm the virus, it is seldom necessary. Because EEE is highly regulated as a “select agent,” a special class of restricted pathogens, samples must quickly be destroyed after lab work is completed.

In humans, viral encephalitis is more treatable, but survivors often have deficits in movement, memory and other areas.

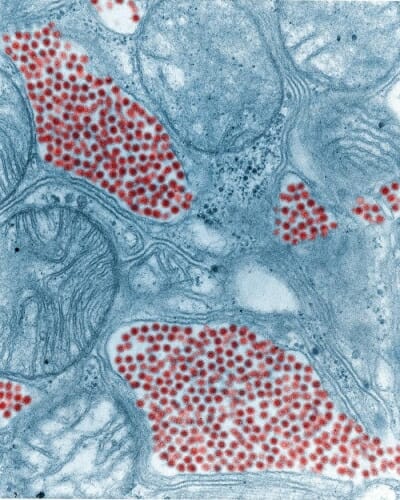

In this colorized micrograph of a mosquito salivary gland, magnified 83,800x, the virus particles are red. Eastern equine encephalitis is transmitted mostly by mosquitoes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention / Fred Murphy, Sylvia Whitfield

Mammals do not directly transmit viral encephalitis to each other; both horses and humans contract the virus through mosquitoes. Birds are the likely “reservoir” for EEE.

Horses are a “dead-end” host for EEE, because the virus level in the blood does not build high enough to be transmitted to a mosquito.

Still, the new finding does have human health implications. “This viral disease is an example of the close relationship between human, animal and environmental health,” Poulsen says. “With a wet spring and early summer, the mosquito vector population is larger, increasing risk to mammalian hosts. While the horse is a dead-end host, seeing disease in non-vaccinated horses is a reminder to minimize standing water, which is the breeding ground for mosquitoes.”

If horses in an area are being infected, people are also at risk, says Poulsen. “While infection in people is rare, it is serious. The risk can be decreased with mosquito avoidance such as clothing and repellents.”