Small Wyoming dinosaur helps rewrite the evolutionary story of birds, flight

An artistic rendering of what Lori, scientifically known as Hesperornithoides miessleri, may have looked like when she was alive roughly 150 million years ago. Image by Gabriel Ugueto

Scientists have long known that birds and dinosaurs are related, but as with many families, it’s complicated.

There are dinosaurs with feathers, but no wings, and dinosaurs with feathery wings that couldn’t fly. Years of study and an abundance of new fossils in recent decades have left researchers making their best predictions as to whom is related to whom, and just where birds first emerged has remained elusive.

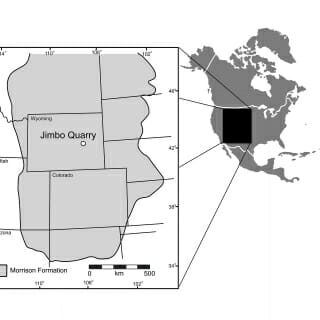

Now, a small, chicken-sized dinosaur discovered by accident while excavating a much larger dinosaur in the Morrison Formation of Wyoming is helping researchers sort out these challenging family dynamics.

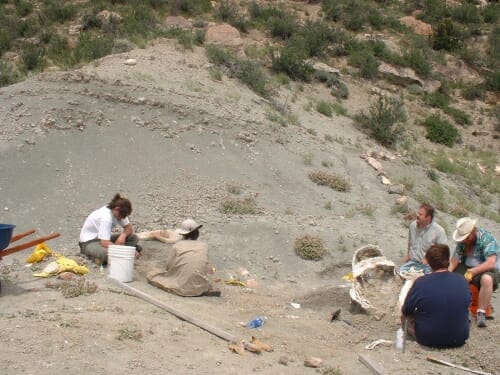

Researchers in Wyoming were excavating a giant dinosaur known as supersaurus when they accidentally discovered a small, winged dinosaur now nicknamed Lori. Lori is helping rewrite the evolutionary relationship dinosaurs and modern birds. Photo by Wyoming Dinosaur Center

That dinosaur, Lori, is the oldest winged dinosaur ever found in North America and the smallest dinosaur found in Wyoming. She is the subject of a study published today [July 10, 2019] in the journal PeerJ. And due to the diligence of the team that discovered her and work led by University of Wisconsin–Madison graduate student Scott Hartman, she is helping researchers better understand the evolutionary relationship between modern birds and dinosaurs.

Lori is also providing new insight into the origins of flight in birds.

“She is the perfect specimen to work with to put all of this together,” says UW–Madison Geology Museum Scientist, Dave Lovelace, lead scientist on the new study. “It’s a big story on how phylogeny is done and how we as scientists can do it better.”

Phylogeny is a way of sorting out the evolutionary relationships between similar species of plants or animals by figuring out, like a puzzle, how each piece fits together. Only, scientists often don’t have all of the pieces. So, they build the clearest picture they can with the pieces they have.

The trouble with this is that as new species are discovered, researchers often are left trying to fit them into what already exists, rather than re-envisioning the bigger picture altogether.

For instance, since 2001, scientists have been adding new species and new traits onto an existing framework called the Theropod Working Group (TWiG), but many species’ relationships remained to be tested, Hartman explains. He and coauthors sought to overhaul the database to incorporate all of the reliable and relevant species information to date, inspired by Lori’s discovery, which also occurred in 2001.

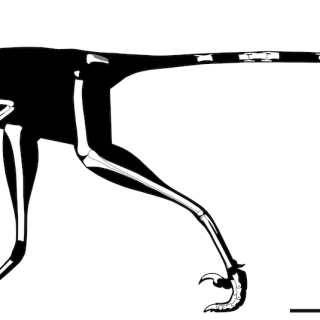

Theropods are carnivorous, hollow-boned dinosaurs that had three toes and walked on two feet. They include velociraptors, Tyrannosaurus rex, and the ancestors of modern birds. Lori is a theropod, closely related to velociraptors.

“We built a phylogenetic matrix that includes 500 species,” Hartman says. “People usually include 200-to-300, so it’s a doubling of the species sample.”

According to independent co-author Mickey Mortimer, based in Washington: “We took the best existing analysis and made it far more precise, more than doubled the number of dinosaurs tested, and ended up with the most detailed test of bird origins yet published.”

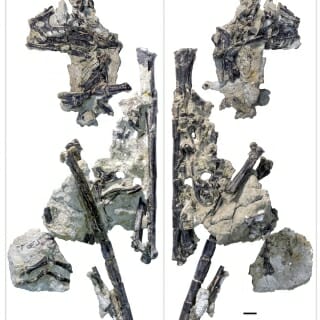

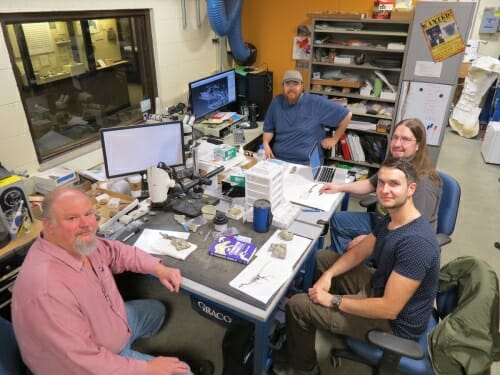

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Geology Museum’s Preparatory Lab, who helped describe Lori, discovered by paleontologists in 2001 in Wyoming. Photo courtesy of study authors

The analysis found that none of the earliest winged dinosaurs in the theropod family could fly. Flying dinosaurs show up in branches with flightless ones multiple times over evolutionary time, suggesting that dinosaurs developed pre-adaptations to flight, including feathers and wings, millions of years before birds took to the skies.

It also shows that avian flight may not have evolved until relatively late – in the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous, between 160 million and 100 million years ago.

“Archaeopteryx is usually assumed to be on the bird line, but our analysis does not find this,” says Hartman. “Archaeopteryx may not be part of a true bird lineage at all; it’s buried (in the phylogenetic tree) with non-flying dinosaurs.”

Lori represents something of an intermediate on the phylogenetic tree. She has features that are similar to birds, such as a well-developed wishbone, but also those that differ, such as large, bladed teeth.

She was found in the thick rock and debris covering an excavation intended to unearth the giant dinosaur Supersaurus vivianae, whose shoulder blade alone is roughly the size of a grown man.

“We were removing a ledge of overburden rock and found — unfortunately with a shovel — some tiny, delicate bones poking out,” says Bill Wahl, preparation laboratory manager at the Wyoming Dinosaur Center and the paleontologist who helped find her. “We immediately stopped, collected as much of the bones as possible and spent the next few days frantically searching for more.”

Unfortunately, her fossilized skull and other small parts were damaged before she was discovered, but a partial skull and much of the rest of her remain. Geologic evidence at the site suggests she would have lived in a wetland-like environment. Says Hartman: “She was maybe more heron than desert-dweller.”

However, he adds: “Lori probably would have had wing feathers, but they would have been too small for her to fly.”

Scientists have several theories to explain why dinosaurs may have evolved feathers and wings before they evolved flight. They may, for instance, have helped them run, Lovelace says.

“All of a sudden you have these fuzzy things and your arms are outstretched and you’re running and it reduces drag,” he says.

They may also have helped insulate the animals and their developing eggs, been useful for attracting mates, and, as researchers at the University of Montana have found, feathers and wings may have helped them escape predators by allowing them to propel themselves up trees and other sloped terrain.

Lori, officially named Hesperornithoides miessleri — in honor of the Miessler family on whose private land she was found — will be on display for the first time beginning Friday, July 12, 2019, at the Wyoming Dinosaur Center. The Center, says co-author Jessica Lippencott, is committed to preserving her and other Wyoming specimens for research and for public display.

The study represents the first time Lori has been described and it was funded, in part, by crowdsourced donations. Says co-author and visiting scientist at the University of Manchester, Dean Lomax: “We are grateful to everybody who kindly donated and helped make this project happen.”

In addition to donations made through Experiment.com, the work was also funded by the Jurassic Foundation and the Western Interior Paleontological Society.