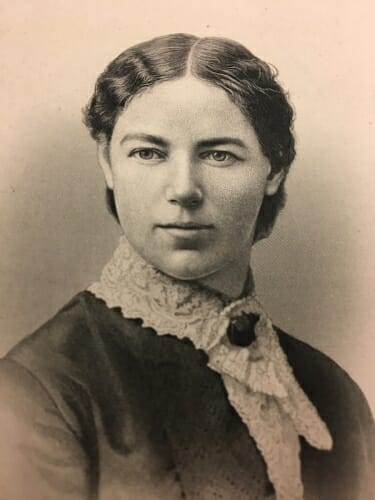

First female valedictorian became renowned suffragist

Like many young people away at college, Clara Bewick sought to reassure her family that she was doing just fine.

“Let me say, for the 50th time, do not, under any circumstances, worry about me,” she wrote in a letter home.

If her family members were a bit jittery, they can be forgiven. Bewick was writing in 1867 from the campus of the University of Wisconsin, which only recently had begun enrolling women.

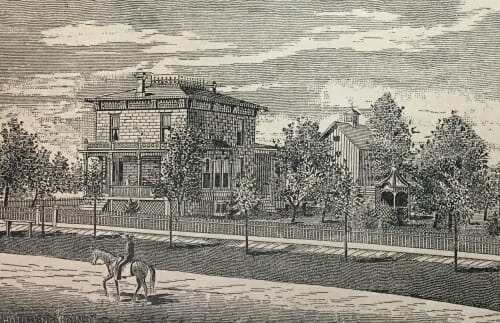

Bewick’s commencement address from June 22, 1869, brims with gratitude for the UW community. A reporter for the Wisconsin State Journal wrote that the essay “was read in a very distinct, self-possessed manner and contained many excellent thoughts.” Wisconsin Historical Society

Two years later, Bewick would be among the first class of six women at the university to graduate with bachelor’s degrees. Her classmates selected her valedictorian.

It was a prescient choice. Bewick would go on to become a prominent journalist, a tireless women’s rights advocate, and a suffragist of national renown. Her accomplishments and influence would do much to advance the cause of women in higher education.

But first, she had to negotiate university life.

In a letter to her grandparents that is now part of her personal papers at the Wisconsin Historical Society, Bewick expressed frustration over the limited class selections available to students like her who were progressing through their studies more rapidly than their peers.

“I had Latin, mental philosophy and geometry — only three studies,” she wrote. “I asked Prof. Pickard what else I should take, and he said, ‘Nothing.’ But I felt as if I ought to do more, and so, as there was nothing else I could take, I decided to go into the advanced Latin class, which was reading Cicero.”

Years later, testifying before Congress on women’s suffrage, she would quote Cicero to make her case.

. . . .

Bewick impressed people from a young age. Born in England and raised on a modest farm near Windsor, Wisconsin, she was studious and bright, known for memorizing long literary passages.

As a teenager, she began teaching in a Dane County school. At 19, she entered UW. Her letters and diary entries suggest a college student enjoying campus life and appreciating the opportunities before her. Her studiousness continued to impress people.

“She filled every hour with recitations and prepared for class by unstinted hours of study,” one female classmate later remembered.

Bewick’s commencement address from June 22, 1869, brims with gratitude for the UW community. She addresses the historic nature of the moment only briefly while acknowledging the presence of the Board of Regents.

Bewick’s commencement address from June 22, 1869, brims with gratitude for the UW community. She addresses the historic nature of the moment only briefly while acknowledging the presence of the Board of Regents.

“We thank you, gentlemen, that through your efforts, we graduate today from a regularly organized female college. We thank you for your recognition of woman’s wants and woman’s capabilities.”

A reporter for the Wisconsin State Journal wrote that the essay “was read in a very distinct, self-possessed manner and contained many excellent thoughts.” Bewick, the reporter said, “was heartily applauded when she closed.”

Bewick spent the next few years teaching Latin and history to female students at UW while taking graduate-level classes in French, Greek and chemistry. Alas, her time at UW ended on a sour note in 1870 over a pay dispute. She felt strongly that her experience and her performance as an instructor the prior year entitled her to a raise.

“She took a bit of a stand but probably misjudged her negotiating position,” says John Holliday, of Gold Coast, Australia, a second cousin twice-removed of Bewick’s who is researching a book on her life. “They said no and told her she must decide whether to stay or resign. She resigned.”

The following year, she married Leonard Wright Colby, a UW law graduate, and became known professionally as Clara Bewick Colby.

. . . .

The couple soon moved to Beatrice, Nebraska, where Leonard set up a thriving law practice and Clara began the professional and civic-minded endeavors that would define the rest of her life.

She established the Beatrice Public Library, served as principal of the school district, and helped form the Nebraska Woman Suffrage Association, serving as its president for 13 years. A prolific writer, she founded, in 1883, The Woman’s Tribune, considered for several years the voice of the American suffrage movement. By this time, suffrage leaders on the East Coast such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had taken notice.

“They liked her western, youthful and educated perspective,” says Kristin Mapel Bloomberg, a professor of women’s studies at Hamline University who is writing a book on Bewick Colby. “She was viewed as someone who could represent the kind of ‘ideal America’ on the emerging frontier.”

The tragedy of ‘Lost Bird’

Clara Bewick Colby and her husband, Leonard, had no biological offspring but raised two children. The story of their adopted daughter illustrates a painful aspect of America’s treatment of Native people. Read more

Bewick Colby published the Tribune for 26 years, largely by herself and on a shoestring budget. It was the second-longest-running woman suffrage paper in the U.S.

Large crowds attended Bewick Colby’s speeches on suffrage and women’s rights. She also spoke and wrote about many other topics, including women’s access to education, justice for farm women, better working conditions for lower-wage workers, and the plight of Native American women.

“She was well-known as a very good speaker because she wasn’t overly radical,” Mapel Bloomberg says. “She had a way of talking to regular people that was really relatable.”

. . . .

The Colbys divorced in 1906 following a long separation. The development strained Bewick Colby’s finances and drew unwanted publicity to the suffrage movement. She became an example of the kind of woman that national leaders thought would be viewed unfavorably by the public.

“It was the idea that if you gave women more rights, they would divorce their husbands and kick the men out. So despite all the wonderful things she’d done, she ended up being shut out of the U.S. suffrage movement,” Mapel Bloomberg says.

Large crowds attended Bewick Colby’s speeches on suffrage and women’s rights. “She was well-known as a very good speaker because she wasn’t overly radical,” says her biographer Mapel Bloomberg. “She had a way of talking to regular people that was really relatable.” Wisconsin Historical Society

Bewick Colby remained very involved in the cause, however, spending more than a year in England working on British suffrage. In 1916, while crossing the U.S., she developed a cold that turned into pneumonia. She died that year at age 70, penniless, at her sister’s home in California. Four years later, the 19th Amendment gave women the vote.

“Her story is one of great achievement, with some awfully difficult challenges that she had to endure,” Holliday says. “She wasn’t the founder of the movement, and she wasn’t there at the finish, but she was one of the major influencers.”

Bewick Colby is not as well-known as other suffragists because she was literally written out of the narrative, Mapel Bloomberg says.

“The suffragists who controlled the movement also controlled the history of the movement,” she says. “Clara and a number of others were not included in those histories because they were seen as less desirable examples of what suffrage should look like.”

Bewick Colby’s personality also played a role, Mapel Bloomberg says.

“She had that Wisconsin pioneer work ethic,” she says. “She always saw herself as someone who did the hard work behind the scenes without needing to get a lot of individual credit.”

As the centennial of the 19th Amendment nears in 2020, there is considerable scholarly energy in the field of women’s history around recovering and re-contextualizing women like Bewick Colby as vital actors in the U.S. suffrage story, Mapel Bloomberg says.

In her commencement speech at UW, Bewick Colby told her fellow graduates that solemn responsibilities awaited them. She urged them to look at the past lovingly but not regretfully.

“A broader and nobler life lies before us,” she said. “Let us hasten to make it our own.”

. . . .

This story is part of the UW Women at 150 series marking the 150th anniversary of the first women receiving undergraduate degrees at the university. Over the course of this academic year, University Communications will feature stories that celebrate the accomplishments of women at UW–Madison through the decades and recognize the challenges that remain, as well as the ways our views of gender have evolved and expanded.

Tags: alumni, history, UW Women at 150