New exhibition seeks to connect WWI’s “staggering losses” with modern medicine

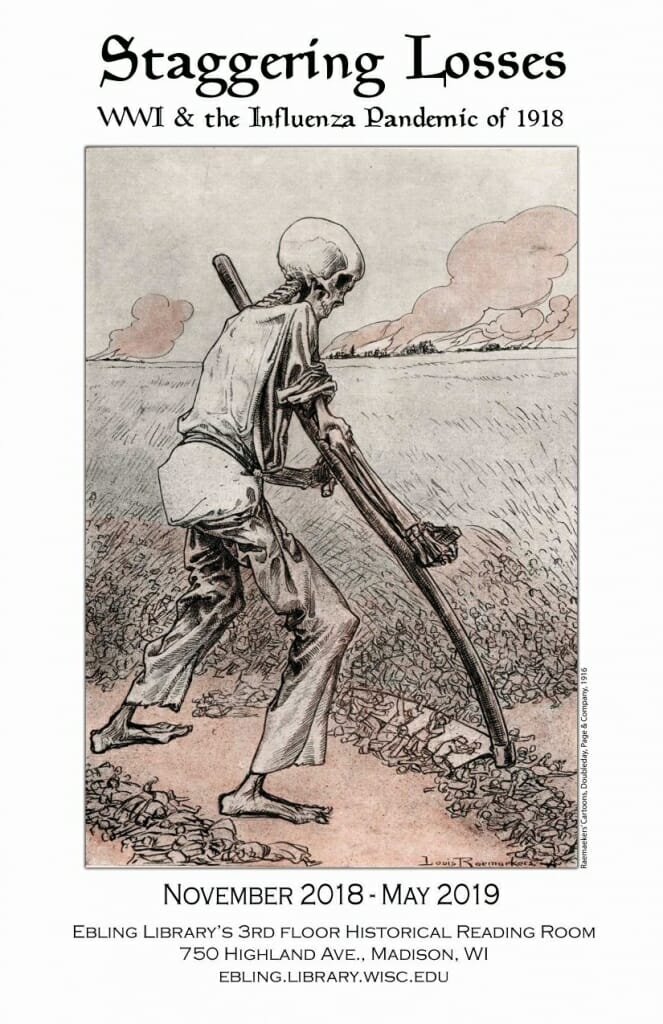

Drawing on Ebling Library’s vast collection of health sciences materials, including early 20th century nursing journals and medical books, as well as UW’s archives, a new exhibition seeks to tell the story of WWI, its impact on modern medicine, and the forgotten people who fought in it. “Staggering Losses: World War 1 & the Influenza Pandemic of 1918” officially opens Thursday, February 7 and runs through May. We talked with Micaela Sullivan-Fowler, a librarian at Ebling who curated the exhibition, about what she learned and why people should still care about WWI.

What inspired you to put together this exhibition?

Part of it was the embarrassment of being one of the few health sciences libraries in the WORLD that had not yet done an exhibition to celebrate the Centennial of WW1 (1914-1918). I got the bulk of the exhibition done in December, coming just under the 1918 wire. Also, the Ebling Library has notable collections from that era, especially in its early 20th century clinical and nursing journals and its books on military medicine, and I wanted to highlight those collections. We also have a remarkable WW1 stamp and postcard collection from donors Gerald Estes and Annette Yonke that complements the other material.

Personally, I had two scenarios stuck in my head from that era. I heard one over 30 years ago from historian Lester King, M.D., who was 10 when the 1918 influenza epidemic hit Boston. He told me that as a young boy he and his friends stepped over and played near corpses piled on the sidewalks because the death toll was so swift and appreciable that there were not enough coffins or grave sites to handle the mounting body count. And then my husband, whose British grandfather had been through WW1 and been mustard gassed, had made it home but “was never quite right.” Other than History Channel fare and some reading knowledge of the pandemic, as a historian mainly familiar with the 17th century, the Civil War, and late 20th century, I actually knew (it turns out) very little about WW1. I came up with the title, at the very beginning – Staggering Losses: World War 1 & the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 – essentially hoping to make some sense of the tens of millions that died or were wounded in the War and the tens of millions who sickened or died in the pandemic.

What were the most interesting things you learned in the process of putting the exhibition together?

That it is, perhaps, one of the most crucial world events that ever happened, that it continues to have lessons for the modern world, and that the losses were not simply in the lives, limbs, animals, creative or intellectual opportunities and relationships to those that died, but also in the lost opportunities for improved race relations, peaceful agreements and women’s inclusion in the body politic following the war.

The pandemic affected the life expectancy of the planet because of the mortality created by a virulent H1N1 virus. The numbers of young men and women, both from the war and the pandemic who died, was so extraordinary that it affected an entire generation. So many died that it affected the work force, the economy, marriageable populations, childbirth rates, education – the list goes on.

On a more specific level I learned about trench warfare, rats, mud, (anecdotally the two most mentioned entities in WW1 journals, poems, letter were rats and mud), how pivotal animals were to each of the Allie’s efforts. Not just horses, but mules, camels, pigeons, elephants and dogs served their countries to the tune of, again, millions. That the injuries from machine gun fire, mortar blasts, flamethrowers, grenades, mustard gas, tank fire, bombs dropped from Zeppelins and airplanes, and shrapnel laden ammunition were some of the most disabling, hideous, mutilating injuries ever seen – and that a woman sculptor in France helped make some of those devastated faces whole again. Oh my gosh, that shell shock could even affect stalwart soldiers like the Zouave, that souvenirs came in artifacts but also in venereal disease and psychological trauma from the death toll people had witnessed. That we lost physicians, nurses and ambulance drivers who were in the prime of their professional careers, who left their wives, children, practices, research and community projects. That the African American, Latino and Native American participants, while there because of their patriotism and verve, were marginalized in the actual camps and combat environments.

And, finally, that the nursing literature often anecdotally mentions the various treatments that the army was using to combat infection, arguably “blessing” those treatments at the Front with a “stamp of approval” that no double blind trial or peer reviewed process would have approved.

How did WWI impact healthcare?

In countless ways, much like previous conflicts have done. So much of how we handle anesthesia, surgery, prosthesis, wound and injury treatment, chest trauma, gangrene, plastic surgery and convalescence was informed by the helter skelter, large scale landscape of WW1.

Consider the Battle of Somme, where 54,000 British troops were killed or wounded in one day The management of which limbless man should take priority over someone who had lost half his face, the chest wound versus the gangrene from an open fracture sustained from too much time spent in the trenches. All of that decision making and transport was fine tuned over a four year period amongst the most challenging of circumstances.

By the time America officially entered the war, most Americans, including physicians, were patriotically behind the effort. While they had a Hippocratic responsibility to prevent the wounded from dying and to be at places with the most severe medical need, they also tried to make the wounded fit again for battle. They had never seen such dramatic wounds in such extraordinary numbers. This landscape represented unlimited research possibilities. Treatments like BIPP (Robinson), antisepsis (Dakin & Carrel), debridement (Tuffier), reconstructive surgery, (Gilles) and innovative prosthetic devices were developed or fine-tuned during the war.

War was perceived not as the enemy of medicine but as its teacher. According to some historians, war even provided opportunities to demonstrate the worth of a specialty, such as psychiatry, surgery, orthopedic and cardiology. The war offered exceptional experience and novel, resourceful treatments that should still garner our deepest respect 100 years later.

Is there a story of someone who fought and/or died in WWI that particularly stood out to you?

UW alumni Harry Dillon, class of 1914, Second lieutenant in the U.S. Army, 26th Infantry. He was the son of James Dillon and Eddie E. Full of Mondovi, Wisconsin, and a graduate of the college of Agriculture. He was working on healthy silage for draft horses before he left to fight. He had received the French Croix de Guerre for bravery at the vicinity of Soissons. A shrapnel shell killed Harry on October 2, 1918 – just a little over a month shy of the Armistice – in the battle of the Argonne Forest. His horses must have missed him.

Three people who made it through the war: Vincent, a musician and stretcher bearer who collected the wounded from the battle field; Miss, an American nurse; and Leslie Buswell, an ambulance driver and chronicler. The three were essentially in the same region of Marne, France. Did they meet? Did Vincent play for the troops that Leslie later transported and Miss nurtured and treated?

And, among so many others, a patient that Miss speaks of in her journal. He was a black pearl diver from Guadeloupe who came to France to support his colonial nation and died while under her care. As he lay dying, “’O mon bon Dieu,’ [oh my god in French] and it was over, and nothing remained but a radiating smile. I went to lay him away among the heroes; and if ever I doubted how to die, my black pearl fisher from Guadeloupe has shown me the way.” Just seven out of millions, each one with their own power, family, and loss, resonating for decades to come.

What was the process of gathering all the exhibition’s materials (journals, photographs, etc.) like?

Monumentally satisfying and frustrating and a stunning lesson in conjunctions between social, cultural, medical, political, literary, and personal themes. Historians work with secondary materials, like historical interpretations, and primary materials, like articles, books, journals, poems, and letters. This could take years to identify, locate, gather, research, and then incorporate it into a story line of related themes. The online databases at UW, databases like ProQuest Newspapers, the books and journals available at Ebling, the Wisconsin Historical Society, the UW Digital Collections, and at the UW Archives at Steenbock Library all revealed pieces of the stories I hoped to tell in 13 distinct cases.

Having so much primary material in original form, as well as digital versions in online forms, allowed me to find the relationships between topics, like the place of animals in the war effort and the sweeping impact of the influenza pandemic. For every article, story or clipping I found on injuries, triage, trench warfare, influenza prevention, or the role of people of color in the conflict, I found 12 more potential lines of inquiry and rabbit holes of research I could go down. There is an endless font of stories still to tell from WW1.

I think the beauty of WW1 is that it’s far away but not so far away that we don’t have relatives that might have been part of the conflict. Colleagues and friends have mentioned grandfathers, fathers and uncles who died of influenza, forever altering the trajectory of their families. It was to be the war that ended all wars, but we still struggle with many of the conundrums they struggled with. Those tens of millions were singular voices who were part of a profound set of circumstances, and who lost their lives so that we could go on. In the words of an anonymous blog comment, “we should try to look after [that] peace a bit better in their memory.”

What do you hope people take away from the exhibition?

Peter Jackson, the director behind films like the Lord of the Rings, recently produced “They Shall Not Grow Old,” a movie that took archival film and amazing technology and breathed life into footage from WW1. The film reanimated the soldiers, we could hear their voices, experience the mud, anticipate the missiles, sigh at their laughter, cry for their loss. Jackson said that when all was said and done, the film was a tribute to his grandfather, a soldier in the war, who, like my husband’s grandfather, made it home but was never whole again. We need to remember all those fathers, grandfathers, sons, mothers, daughters, our relatives that fought, cared for, and participated, whether in the trenches or at home, in the war in whatever capacity. I want people to have “aha” moments, to lean into the text heavy display cases and gather little bits of drama and bits of humanity and discover things about medicine and trauma and disease and race and mules and gas masks and flu and homesickness that they never knew or never appreciated. And go home and read more about it and to acknowledge the grief and loss that our fellow citizens suffered. It reminds us of our shared humanity.

What’s next?

I hope to create some sort of online version of the cases, as once the installation is done, the exhibition is gone. Perhaps do a blog following up on all the threads I couldn’t fit in those 13 cases. I will be speaking about the exhibition at Wednesday Nite at the Lab on Wednesday, March 6th, at 7:00 pm if they’d like to see some images and hear more about the stories I discovered. I didn’t know too much about WW1 or the pandemic. Now, I’m smitten. It resonates in a way that has modern meaning for all of us. Come see for yourself!