Bird observing course an experience in finding passion for nature

Early morning mist blankets the air above flocks of birds roosting in a pond at Goose Pond Sanctuary. Photo by Mason Muerhoff

ARLINGTON – The students were thrilled that, for the first time all semester, they could conduct their lab outing without huddling under winter coats. Though it was foggy and not yet 8 a.m., the mercury had already reached above 40 degrees as they exited vehicles at Goose Pond Sanctuary in Arlington, Wisconsin, for that day’s meeting of their Birds of Southern Wisconsin class.

The course, taught by Forest and Wildlife Ecology Professor Anna Pidgeon, spans from winter to mid-spring and takes students on weekly outings around south-central Wisconsin, from Cherokee Marsh in Madison to Middleton’s Pheasant Branch Conservancy. The students must sometimes brave the elements to collect observations of Wisconsin’s overwintering and migratory birds.

Students Cameron Wagner and Allie Olson, left to right, stand behind a spotting scope at Goose Pond Sanctuary as they survey the water for species of birds on their watch list. Photo by Mason Muerhoff

“One morning it was 10 degrees and a blizzard,” said a shuddering Kristin Brunk, the lead teaching assistant for the day’s lab. “We saw a cardinal, a chickadee, and that was about it.”

But most of the students agreed that it’s worth it, as they peered through spotting scopes at a pair of kestrels in the branches of a far-off oak and listened to the distinctive calls of a ring-necked pheasant.

The intent of the class is to teach students how to learn about, observe and identify the bird species commonly found in southern Wisconsin and elsewhere around the country. By semester’s end, through a combination of in-class lectures and outdoor field trips around the region, the students should be able to identify 234 different bird species by sight and 125 different calls.

A tree swallow flies to meet another swallow on a bluebird box at Goose Pond Sanctuary. Photo by Mason Muerhoff

Although students may end up forgetting specific species, the skills are applicable to other systems of learning that students may venture into, Maia Persche, another teaching assistant, and Brunk said.

“Before this class, I was fairly afraid of birds, but it seemed like fun to get out of the classroom and learn in the field,” said junior Lilly Mann. She described being excited when, on a trip to Florida over spring break, she was able to identify a mourning dove and take note of species new and unfamiliar.

“I wish I had had a class like this when I was learning the birds,” said Brunk, who is a graduate student in Pidgeon’s lab. “I think this is one of the science classes that makes UW really unique.”

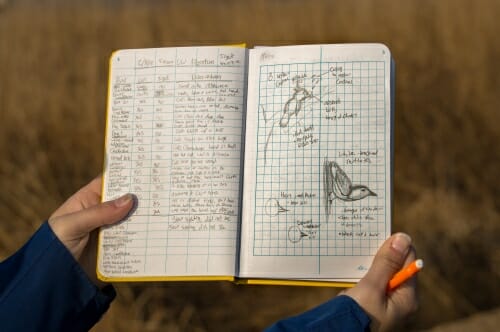

Allie Olson, senior, displays the categorical observations and sketches she has recorded in her Birds of Southern Wisconsin field journal. Goose Pond Sanctuary. Photo by Mason Muerhoff

In the field on this relatively balmy day, Persche and Brunk would call out to the 20 students where, among the cacophony of geese in the ponds that give the site its name, they could train their binoculars to catch a glimpse of something interesting or new.

The TAs also aimed the spotting scopes on specific birds they wanted the students to observe and record in the field notebooks they carried to every outing.

“There’s a broad group (of birds) we’re expecting to see,” Persche explained, but: “Spring migration does bring a lot of new ones, too.”

They were delighted to observe tree swallows, eastern meadowlarks and eastern phoebes for the first time all season. And, as the class made observations, a few tree swallows darted in and out of a bluebird box positioned in high grass just off the site’s main road.

Common at Goose Pond Sanctuary, only 30 minutes from metropolitan Madison, are Canada geese, red-winged blackbirds, robins, coots and ducks. The kestrels nesting in the tree above the prairie restorationist’s farmhouse at Goose Pond were a rare treat, but as Sanctuary Manager Mark Martin explained, the birds have been more common at the site in recent years. Ten pairs now routinely nest there, he said.

In fact, the Sanctuary is home to 1600 pairs of nesting birds, Martin informed the students.

As the morning grew later and thicker fog rolled in, several tundra swans alighted on the pond in the midst of the geese and other more common waterfowl. The noisy-but-obscured pheasant, a non-native bird introduced to Wisconsin from Asia, occasionally drew the group’s binoculars.

With each new bird they observed, the students furiously scribbled down notes in their journals, including identifying characteristics and birdcalls.

Senior Allie Olson’s field notebook was full of delicate and detailed illustrations that help her identify key characteristics, like the plumage on the breast of certain woodpeckers.

“It gets easier (to identify the different birds) as you go,” Olson said. “But the calls can mix together.”

In their journals the students were also expected to record phenology events – cyclic and seasonal phenomena, like the onset of breeding and courtship in some species.

These kinds of events help ground the bird-focused course in the broader lessons associated with observing in nature. The students may note that late-season snow can pose challenges for migrating birds in search of shelter and food, or that early spring blooms can result in food sources that appear and disappear before birds have even arrived.

Making time to observe birds yields opportunities to note the interconnectedness of the natural world and how dependent some species are on specific habitats and the climates to which they are adapted. It can encourage students to think about conservation, Persche said, and the benefits of a healthy environment.

As if to prove the point, an eastern tiger salamander slowly crawled across the road in front of the students as they made their way to another pond nearby. Some stopped to take photos and express sympathy for the cold-blooded animal making a beeline for the water.

The class “provides a different way of learning than a typical course would,” Persche said. “There is no other course where you literally memorize bird calls. It utilizes a different part of your brain.”

Birds of Southern Wisconsin is a course offered cooperatively by the Departments of Integrative Biology, Forest and Wildlife Ecology, and Animal Sciences, typically in the spring semester.