Monkey study shows a path to monitoring endangered species

A Brazilian-American research group has just published an unusual study outlining data needs for monitoring the survival of monkeys called muriquis that live in patches of forest in Brazil.

“If you want to preserve the muriquis, exactly what do you need to know?” asks Leandro Jerusalinsky, one of the authors of a report published today (Dec. 13, 2017) in the journal PLOS ONE. “This was the essential question, focusing on identifying population trends and conservation priorities.”

“Where do you need to go, and what numbers or qualities do you need to focus on?” adds Jerusalinsky, who leads the National Action Plan for the Conservation of Muriquis at Brazil’s National Center for Research and Conservation of Brazilian Primates, linked to the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation.

A southern muriqui in its natural habitat. “The two muriqui species live in one of the five most biodiverse hotspots in the world,” says researcher Karen Strier. © Pró-Muriqui Association (used with permission)

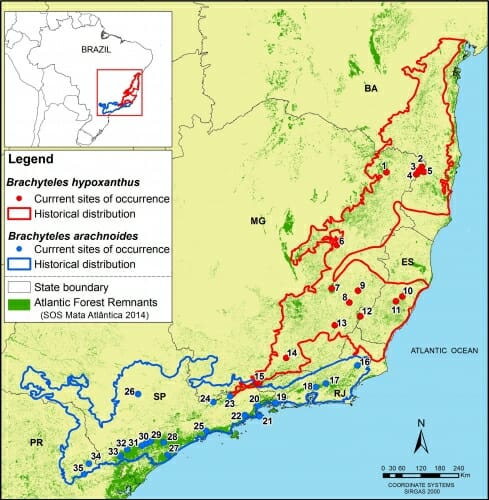

“We think this may be one of the most comprehensive efforts to analyze the data monitoring needs for ensuring the survival of an endangered animal,” says first author Karen Strier, a professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, who has observed muriquis in Brazil for 35 years. “The two muriqui species live in one of the five most biodiverse hotspots in the world — for both plants and animals, but the southeastern Atlantic Forest is the center of Brazil’s economy and population, and so this habitat has long been chopped up by development.”

At most, 2,300 muriquis survive in the wild, including fewer than 1,000 members of the northern species, and an estimated 1,300 for the southern species. “Monitoring demographic trends is essential for management programs, including translocations,” explains co-author Fabiano de Melo, a professor in the forestry engineering department at the Federal University of Viçosa.

Map shows location of northern muriqui (red) and southern muriqui (blue). Circles show specific locations of remnant populations. Karen Strier and co-authors, PLOS ONE

Ensuring that the species survives requires an accurate picture of the different populations, says co-author Mauricio Talebi, professor of primatology and conservation at the Federal University of São Paulo, Diadema campus. “One of the problems we have is that if monitoring uses different methods, the results are not comparable. When we worked on the national action plan for muriquis, we identified gaps. There are big differences in habitat conditions for the northern and southern species, but we still need a standard monitoring system for the various locations.”

Monitoring the health of an endangered species can entail much more than just counting individuals or breeding pairs, says Strier. “Population counts at particular sites and in total don’t require a big labor force, but we are usually interested in other factors, such as genetic uniqueness or geographic importance: Could this site be used to make a corridor linking isolated populations to enhance genetic diversity?”

More monitoring can answer more questions, Strier says. “If you want to understand past or future changes in demographics, or why a population is growing or declining, you will also want to know the sex ratio and what proportion of females are carrying babies. This takes more time, and more expertise.”

Strier, who leads one of the longest field studies of primates in the wild, calls muriquis “the most amazing primates in the world. They have a very low rate of aggression, and have been called ‘hippie monkeys.’ Females are independent and promiscuous, males don’t dominate them, and there’s no real hierarchy among males or females. They spend a lot of time hugging and socializing.

“If you are aiming at avoiding extinction, you need to ask a lot of important questions,” says Strier. “Are you trying to reach the highest genetic diversity? The highest demographic probability of success?”

Monitoring plans must also take feasibility into account, since some places, through topography or ownership, are impossible to get to. Decisions can be problematic if they are made on the fly or based on incomplete information, Strier says.

Another factor that plays a role in monitoring decisions is sites that are on the fringe of species’ habitat. Outliers in terms of altitude or longitude may be the first to die as climate changes. But a relatively cool and underpopulated site today could become an important refuge as climate warms.

Through the work of Strier and a growing number of Brazilian researchers, the plight of the muriquis has become clear, and the primate has emerged as a charismatic animal in desperate need of help, with both species now listed as critically endangered.

“Interest in muriquis has been growing,” says Talebi. Already, he says, the ideas in the monitoring framework are starting to guide his work program of monitoring the southern muriqui.

The same is true for de Melo, who is experimenting with technology, including the use of thermal cameras mounted on drones, to count northern muriquis.

One key factor, called “implementability,” focuses on access, and while some sites are closed to researchers, Talebi says some private landowners have been establishing muriqui reserves.

Muriquis are also getting help from the recovery of landscapes that were converted to farms and then abandoned decades ago, says Strier. “Seeing the resilience of nature makes me more determined than ever. We can’t reverse past assaults to the planet, but we can do everything we can to stop them and give the animals and plants a chance to come back.”

Strier sees the thoughtful processes detailed in the new study as a foundation for a new generation of scientists. “If somebody wants to know how to promote muriqui preservation, this study would be a roadmap. It gives you an idea where to start, and where to focus. We hope it will also serve as a template for scientists concerned with other endangered animals.”

Funding for this project came from Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, Doctum College Teaching Network, Caratinga, Minas Gerais, Brazil, and Conservation International.