Charles Bentley, pioneering UW-Madison glaciologist, dies

Charles R. Bentley, an intrepid University of Wisconsin–Madison glaciologist and geophysicist who was among the first scientists to measure the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in the late 1950s, died Aug. 19 in Oakland, California. He was 87.

Bentley spent the bulk of his career studying the Antarctic Ice Sheet and the continent beneath it.

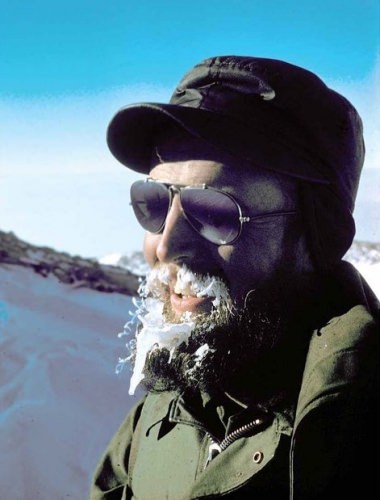

Glaciologist Charles Bentley was one of the first scientists to measure the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

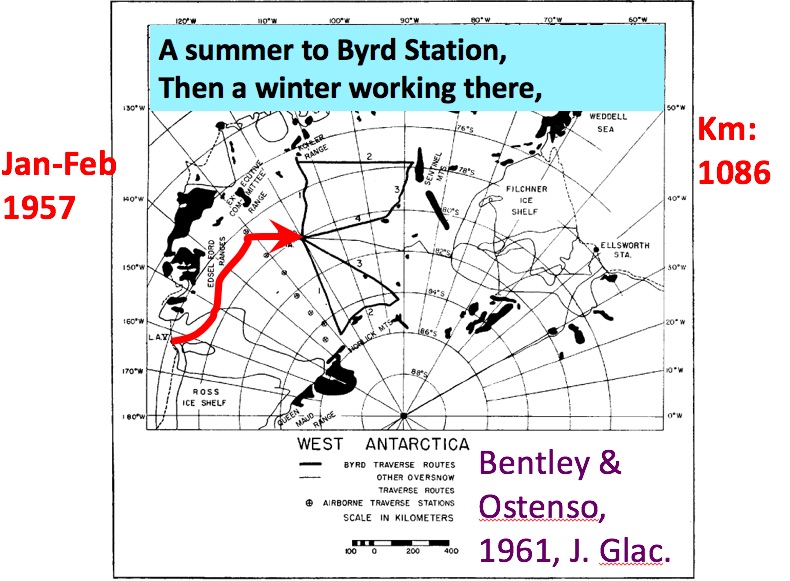

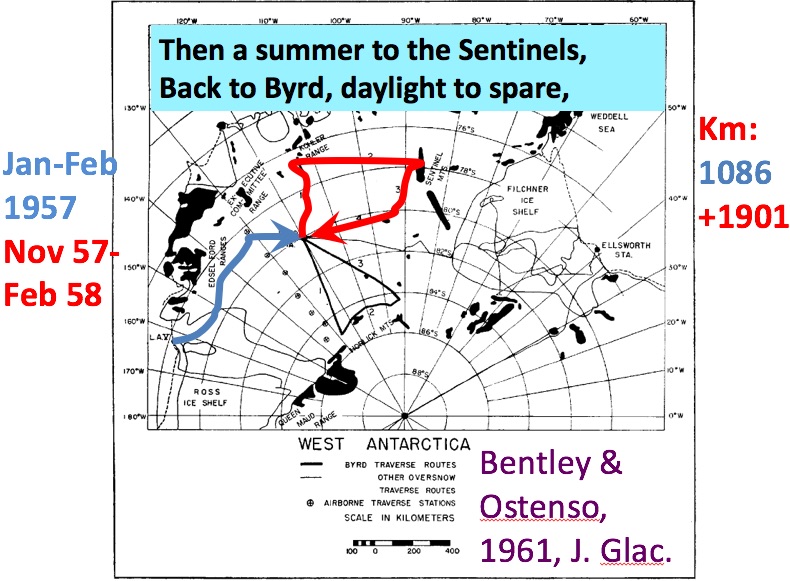

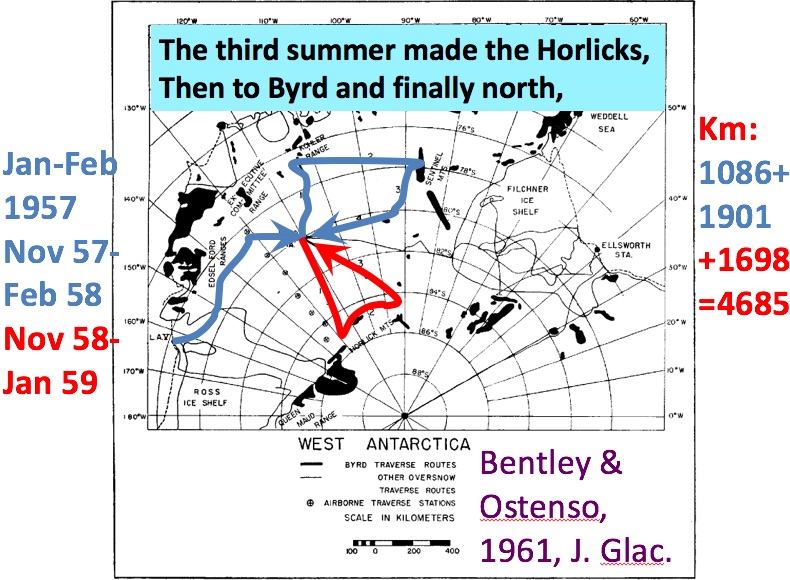

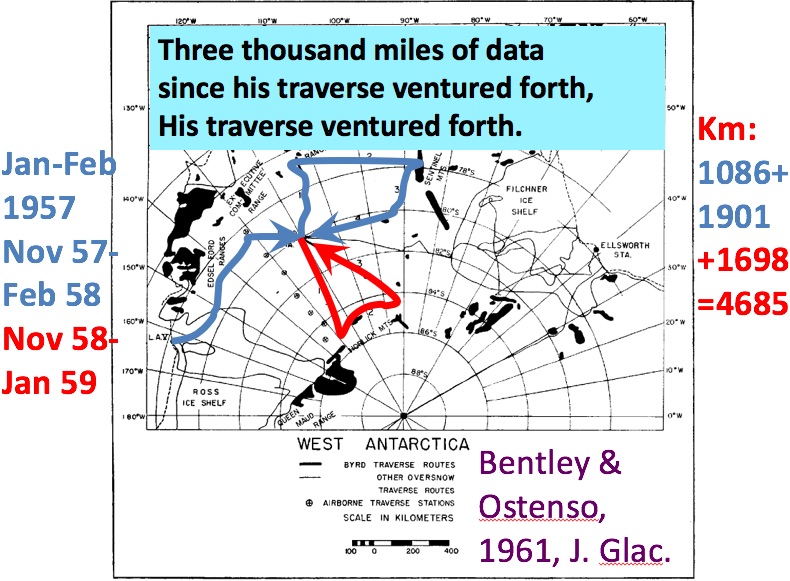

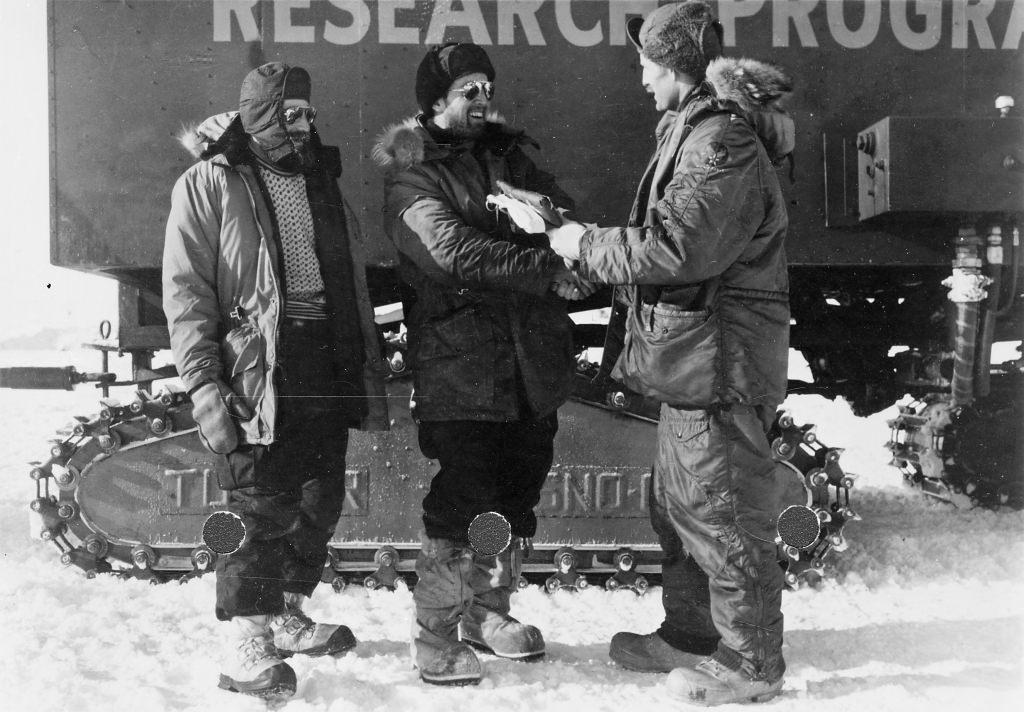

Beginning in 1957, Bentley spent 25 consecutive months on the ice in Antarctica, at a time when scientists from around the world were converging on the continent as part of the International Geophysical Year. During that time, he served as the seismologist on a five-person expedition that motored in tracked vehicles called Tucker Sno-Cats from Little America (a U.S. base near the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf) to Byrd Station in interior West Antarctica on a nearly 700-mile traverse. After wintering over at Byrd Station, Bentley and his colleagues continued their explorations of the continent for a total of almost 3,000 miles of traversing the then almost completely unexplored Antarctic.

During the expedition, Bentley and his colleagues made the first detailed measurements of the depth of the ice sheet. To measure the underlying snow and ice, the team unspooled hundred of meters of cables attached to geophones set on the ice surface to record explosions set off in the ice. The explosions sent sound waves to the bottom of the ice sheet, which reflected back to the geophones to provide a measure of the depth of the ice. To their surprise, they found the ice sheet, which in places is as much as 3,000 meters thick, to be as far below sea level as it was above, making it a marine ice sheet.

That finding resonates today as marine ice sheets are particularly vulnerable to melting and collapse in climate change scenarios.

Beginning in 1957, Bentley (center) spent 25 consecutive months on the ice in Antarctica, at a time when scientists from around the world were converging on the continent as part of the International Geophysical Year. UW-Madison Archives photo

“During those first 25 months in Antarctica, Bentley led geophysical traverses that fundamentally changed our view of the ice sheet — far from being a thin layer draped over high mountains, the ice in places was well over two miles thick, with a surface high above sea level but a bed that plunged far below, including into the Bentley Trench, the deepest point on the Earth’s surface not now under the ocean,” says Richard Alley, a former student of Bentley’s who is now the Evan Pugh Professor of Geosciences and the EMS Environmental Institute at Penn State University.

Bentley made at least 15 trips over seven decades to the ice. He celebrated his 80th birthday on his last trip to Antarctica in 2009, nearly 50 years after first setting foot on the continent. In Antarctica, Mount Bentley, the highest peak in what are now known as the Ellsworth Mountains, and the Bentley Subglacial Trench, an ice-filled trench the size of Mexico, are named in his honor. “I claim to be the only person with a hill and hole named after him,” Bentley told an interviewer in 2008.

“Charlie was one of our most esteemed faculty and a giant in geophysics and glaciology,” says John Valley, a UW–Madison professor of geoscience. “His students are leaders in studying climate change.”

Bentley was a member of the National Academy of Sciences’ Polar Research Board for nearly 20 years, chairing the panel from 1981 to 1985. He received numerous awards for his work, including the Bellingshausen-Lazarev Medal in 1971 from the Soviet Academy of Sciences, and the Seligman Crystal from the International Glaciological Society in 1990. He was an elected fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Geophysical Union and the Arctic Institute of North America.

Born in Rochester, New York, in 1929, Bentley received his undergraduate degree in physics from Yale and was awarded his doctorate from Columbia University in 1959, nearly two years after successfully defending his thesis. He learned of the delay — the result of failure to pay a $50 dissertation fee — after spending two austral winters at Byrd Station.

Professor Emeritus Bentley inspects the barrel of the Blue Ice Drill, designed and built by the UW–Madison Ice Drilling Design and Operations team. UW-Madison Space Science and Engineering Center

Bentley joined the UW–Madison faculty in 1961 and was the A.P. Crary Professor of Geophysics. After arriving at Wisconsin, he turned his sights “first and foremost on training generations of glaciologists and geophysicists,” recalls Sridhar Anandakrishnan, a Penn State professor of geosciences and another of Bentley’s former students.

Over a long career, Bentley published more than 200 scientific papers and, in addition to characterizing the three-dimensional structure and physical qualities of the ice sheet, he showed that the fast-moving ice streams that lace the ice are lubricated by soft till at the base.

After retiring from the Wisconsin geoscience faculty, Bentley assumed leadership of the Ice Drilling Design and Operations program based at UW–Madison’s Space Science and Engineering Center in 2000, a program he oversaw until 2013. The program builds and deploys drills to recover ice cores and other samples from Greenland to Antarctica.

While Bentley’s scientific contributions to understanding the Antarctic ice inform much of the work still being undertaken on the continent’s ice sheets, he has left one other signal relic for future generations: his collection of chamber music. Leaving Byrd Station after 25 months in 1959, he loaned his records to an incoming seismologist. “He never brought them back. My records are still out there. I always had the idea I could go back and get them.”

Bentley is survived by son Alex (and spouse Emma Bentley), daughter Molly (and spouse Gordy Slack), step-grandsons Jonah Taranta-Slack and Leo Taranta-Slack, and grandson Archer Bentley.

Tags: geology, obituaries, research, science