Changes in land use, climate and agriculture undermine efforts to clean up Madison lakes

Despite persistent efforts, there has been no improvement in the water quality of Madison lakes. Cleanup efforts are being hampered by more asphalt, row crops and intense rainstorms, according to a new study.

Photo: Eric Booth

Efforts to clean up the Madison lakes are being hampered by more asphalt, row crops and intense rainstorms and higher manure concentrations on the landscape, according to a new study from the Water Sustainability and Climate project at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

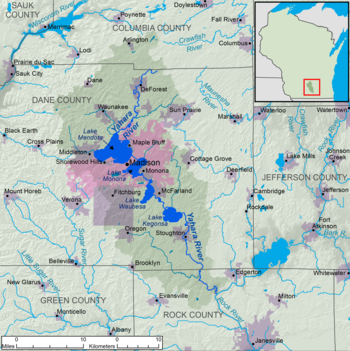

Since the 1980s, government-led initiatives to improve water quality in Lakes Mendota, Monona, Waubesa and Kegonsa have consistently aimed to reduce the phosphorus that enters the lakes by 50 percent. Despite persistent efforts, there has been no improvement in lake water quality.

“Projects are not achieving their goals in part because unaccounted-for changes in climate, land use and agriculture are making it harder to meet them,” says the study’s lead author Sean Gillon, an assistant professor at Marylhurst University in Portland, Oregon, and former postdoctoral researcher on the Water Sustainability and Climate project.

The study is the first formal synthesis of factors undermining efforts to clean up the lakes. Its findings have implications for similar regions around the world.

How people develop land, how farmers farm, and what the local climate is like are leading factors affecting water quality in the lakes, primarily because they determine how much phosphorus and other nutrients end up in waterways, which can degrade water quality.

These factors are constantly changing, yet water quality improvement initiatives typically assume land use, climate and agriculture will remain constant over a project’s lifespan. For example, a 14-year effort focused on Lake Mendota, which lasted from 1994 to 2008 and failed to reach its goal, was based on the assumption that watershed conditions would remain as they were in the baseline year of 1994.

“The climate is changing and land use is changing. And as they change, they could potentially counteract conservation practices. Managers have been looking at only a piece of the whole story,” says co-author Eric Booth, a research scientist for the Water Sustainability and Climate Project.

According to the study, the changes with the biggest impacts are the intensification of livestock operations and the increasing frequency of extreme rainstorms driven by climate change.

“While there are fewer dairy farms in the Yahara watershed today, average herd sizes are larger and each cow produces more milk and thus more manure than cows did forty years ago. With less land on which to spread the manure due to urbanization, there’s a greater concentration of it on the landscape, which has the potential to lead to more runoff,” says Booth.

“Water quality management is important and has positive effects, but efforts are being completely overwhelmed by these other changes that lie outside conventional management approaches.”

Sean Gillon

“We also know that heavy rainfall events have been increasing in frequency, and these have more power to move sediment and phosphorus from farm fields into surface water bodies,” he adds.

Unless these changes are confronted, long-term efforts to clean up the lakes will continue to be undermined, says the study.

Despite the shortcomings, the study shows interventions are having a positive effect — water quality problems have not gotten worse.

“Our results give a clear picture that water quality management is important and has positive effects, but efforts are being completely overwhelmed by these other changes that lie outside conventional management approaches. We’re not going to meet the 50 percent reduction goal if we don’t deal with these drivers,” says Gillon.

Solutions to this challenge could include establishing more realistic goals and incorporating shifting drivers into management models to better predict potential results. The authors also say transformative changes are needed.

“Cleaning up the lakes is going to require bigger changes than are currently represented in best management practices. We hope this analysis will get people talking about the big underlying problems it demonstrates and lead to crafting innovative interventions,” says Gillon.

The study was published earlier this month in the journal “Regional Environmental Change.”

—Jenny Seifert