UW’s own ‘Monuments Men’ leave a legacy

Two pivotal figures in UW–Madison history were part of the effort to recover and preserve art and artifacts plundered during and after World War II. That effort comes to life in the film “The Monuments Men,” a scene from which is shown here.

Photo: Columbia Pictures

Archivists and librarians don’t typically get a lot of publicity. So when Hollywood stars like Matt Damon and George Clooney portray the heroic contributions that archivists made to World War II, it’s a pretty big deal.

That’s why staff members at the University of Wisconsin Libraries are so excited about the new film “The Monuments Men,” opening on Friday, Feb. 7. It’s a chance to spotlight the kind of work that is critical to an institution’s history, yet rarely recognized.

Two pivotal figures in the university’s history – Jesse Boell and Gilbert Doane – were a part of the massive effort to save, preserve and restore art and artifacts to their rightful owners during and after the war. A third individual with UW–Madison connections, music alumnus R. Wayne Hugoboom, about whom far less is known, also took part.

“It’s always exciting when we get to spotlight our connections to a much larger effort,” says Ed Van Gemert, vice provost for libraries and university librarian. “This gives us a chance to celebrate the fact that these artifacts were preserved for the world to enjoy while we give special recognition to Doane and Boell for their work on campus.”

A new exhibit in the lobby of the Memorial Library outlines the type and scope of the MFAA’s work, along with background on Doane and Boell. It includes items on loan from the Kohler Art Library and Mills Music Library as well as extensive photos and correspondence from the University Archives.

“This gives us a chance to celebrate the fact that these artifacts were preserved for the world to enjoy while we give special recognition to Doane and Boell for their work on campus.”

Ed Van Gemert

The exhibit, titled “Our Monuments Men: UW’s Role in Rescuing Europe’s Treasures,” runs from Feb. 7-28.

The UW–Madison Archives’ Found in the University Archives! Tumblr has added its own contributions and plans more throughout the week.

Originally a group of 30 men, the ranks of the Monuments Men – formally known as Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section of the U.S. Army, or MFAA – grew to more than 300 people, including women, in the postwar years.

Members, often with little military training, slipped through combat zones to rescue masterpieces including paintings, treasures owned by victims of the Holocaust, church bells and works of art from some of the world’s great museums.

Archivists like Boell and Doane sat at the critical juncture between recordkeeping and preservation. Work included both records-as-artifacts and the immense task of researching restitution and ownership claims for looted art. Often, archivists reached the artifacts too late to do anything but assess a loss or salvage. Intelligence agents often seized documents and dismantled them before “interested parties” could examine them.

In October 1945, the MFAA began advising U.S. restitution personnel on ways in which to restore the identifiable records and artifacts to the governments from which they originated, as well as disposing of unclaimed and unidentified material. The MFAA’s restitution activities continued until late 1948.

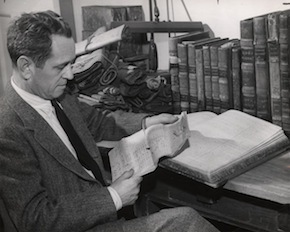

Jesse Boell

Boell was highly qualified for this exacting work. From 1936 to 1941, he served as state director of the national historical records survey, a WPA project employing 350 men and women around Wisconsin.

Jesse Boell examines documents at UW–Madison.

Working under the archivist of the United States in Washington, D.C., Boell spent much of the war in the National Archives as assistant director of the War Records Office, directing the preservation and security of highly classified State Department records.

At the end of the war, Boell accepted his position as an archives officer with the MFAA in Germany. He served in the German military government, participating in the Nuremberg Trials. The type of work Boell undertook not only assisted Allied forces but helped the new German government piece itself together out of fragmented records.

Boell returned to Wisconsin in 1947 as state archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society. In 1959 he was named associate professor and director of the newly formed UW Archives. He became full professor and university archivist in 1962, where he remained until his retirement in 1971.

“The [archives] program really started when Profs. Merle Curti and Vernon Carstensen were writing their two-volume history of the University and found the records in appalling shape,” said Boell, in an interview with the University News Service. “Vernon and I went through stuff and threw some out, and I set up a filing system, as well as a classification and cataloging system, to keep track of the things we kept.”

University archives grew to prominence in part because of the many institutions which celebrated their centennials in the mid-20th century. By the 1960s, Boell was recognized as a pioneer in academic archives.

Gilbert Doane

Doane had become UW’s director of libraries and director of the library school in 1937.

Gilbert Doane

When the War Department requested a character and fitness reference, UW President Clarence Dykstra was only too happy to oblige, calling Doane “a man of unusual ability.” In addition to his integrity and dedication to his work, “[h]e is tall, personable, well-spoken and has a fine command of the language.”

“Besides being a librarian, Mr. Doane has given a great deal of attention to the problems of genealogy, identification of manuscripts and the rendering of judgment on sources,” Dykstra continued, in a letter dated August 2, 1943. “I can well understand that the Army might have very real use for the kind of service which Mr. Doane can render.”

Doane took a leave of absence a month later and left to serve as a captain. A January 1944 letter to his good friend “Dyk” outlined some of the intensive training undertaken by Doane and his colleagues: seven lectures on military organization, four weeks on the administration of occupied territory and significant attention to the history of military government. Doane much preferred the last, given its “decidedly academic flavor” by a Professor Gabriel from Yale.

When Doane retired as a major in 1945, he eagerly returned to the university. He had plenty to do, ranging from the founding of the Friends of the University Library in 1948 to the planning of the new Memorial Library, which opened its doors in 1953. In 1956, he became University Archivist, where he remained until his 1962 retirement.

During Doane’s 20-year tenure, the UW–Madison libraries doubled their holdings and staff and added multiple special collections.

Legacy

Even today, more than 70 years after WWII began, thousands of works of art are still missing. Robert Edsel, who wrote the 2009 book on which director George Clooney based the movie, started the Monuments Men Foundation to honor the personnel of the MFAA, but is also instrumental in continuing the search. The foundation asks for the public’s help to join the hunt.

Boell and Doane left few reminders of their time as Monuments Men in their time at UW–Madison. Perhaps, like many, they were not only unable to share the classified information but preferred not to discuss it.

On the other hand, perhaps these dedicated professionals viewed it as simply an extension of their everyday work – regardless of the scope or location.

Boell’s office displayed the framed words of the archivist of the United States:

“The archivist has a moral obligation to preserve evidence on how things actually happened and to take every preservation of valuable records. On the other hand, he has an obligation not to commit funds to the housing and care of records that have no significant or lasting value.”

In Boell’s words: “Save the good stuff, throw away the junk.”