“I Have a Dream” is speech for the ages

Martin Luther King Jr. gave thousands of speeches in his life, both as a minister and as a leader of the civil rights movement in the United States, but one stands above the rest: “I Have a Dream.”

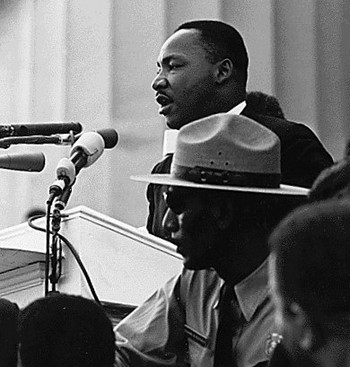

Martin Luther King Jr. delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington D.C.

Photo: National Archives

When UW–Madison Communication Arts Professor Stephen Lucas wrote a book about the top 100 American speeches of the 20th century, “I Have A Dream” came in at No. 1. King delivered the speech on Aug. 28, 1963, during the massive civil rights march on Washington, D.C., and it still has an impact today.

“When I show the speech in class, students continue to be moved by it,” Lucas says. One thing students learn about the speech is that King extemporized the “I Have a Dream” section — it was not part of his prepared text. “He met the needs of the moment and then he lifted the speech above the moment so that it became both timely and timeless.”

Q: What was it about the speech that makes it so memorable even today?

A: The fact that King spoke on the issue of civil rights is a major factor. The other most highly regarded speech in American history is Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which revolves around the Civil War but is inescapably related to questions of race and slavery. King spoke to a live audience of 200,000 people, plus millions more on radio and television, and his speech achieved an exceptional level of rhetorical artistry. The content was perfect for the moment, the tone magisterial and uplifting. While quite different stylistically from John F. Kennedy’s highly praised inaugural address of two years earlier, King’s speech was equally adept in its use of rhetorical devices such as repetition, metaphor, and simile. And then there was King’s unparalleled delivery, with his rich baritone voice functioning like a finely tuned musical instrument.

Stephen Lucas

Q: How does “I Have a Dream” compare to other speeches King gave in his lifetime?

A: “I Have a Dream” is different from King’s classic speech of April 1967 at New York’s Riverside Church announcing his opposition to the war in Vietnam. The Riverside Church speech is monumental, but its aim was to inform and educate, while the aim of “I Have a Dream” was to inspire and motivate. If “I Have a Dream” sounds like a sermon, the Riverside Church speech sounds like a scholarly lecture — though one that captured the total attention of its audience and was a turning point in public opposition to the war in Vietnam. King’s other best-known speech is “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” given the night before he was assassinated. Popular lore holds that King was prophesying his own death, but his message was actually one of optimism about the ultimate outcome of the civil rights movement. The fact that this was King’s last public speech — and one that ended on an extraordinarily poignant note — has given it special resonance over time.

Q: Do you see any signs of King’s influence on speeches that public figures or political leaders give today?

A: He certainly has been a source of inspiration to Barack Obama, both oratorically and in his quest for equal rights and social justice. You can hear moments when Obama’s cadences sound like a toned-down version of King’s, but we have to remember that King’s delivery was perfected in the African-American pulpit. Like other successful speakers, Obama has developed his own speaking style rather than emulating King or any other single person. We should also note that King’s speech is held in esteem internationally. The phrase “I have a dream” has become part of the global lexicon, and the speech is studied around the world, including in China, where there are as many English-language learners as there are people in the United States.

Q: Do speeches still have the same impact today that they did back then? A: People have been bemoaning the decline of oratory for centuries. Even during the golden age of American oratory before the Civil War, there was concern that the quality of public speaking had fallen from the heights achieved during the American Revolution. During the 1960s, it seemed as if the rhetoric of the streets was replacing the rhetoric of the platform; yet the ‘60s produced more memorable speeches than any decade of the 20th century. The tone, tenor and topics of public address have changed over time and with the emergence of new technologies, but the fundamental human drive to use speech expressively and artistically remains alive and well. We should not forget that only five years ago Barack Obama’s run to the White House was fueled by a series of speeches that captured the public imagination. The power of the spoken word endures, and I suspect there will always be moments when we look to our leaders to articulate on the public stage our hopes, our dreams, our fears, and our aspirations.