Four-legged patients – and their blood donors

Pets and other animals have the occasional need to receive blood products, and donors animals play an important part in the work of the UW–Madison School of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital’s work.

Photo: Jeff Miller

As human patients, we expect that a hospital would have an ample supply of blood or plasma on hand for a transfusion, if we needed one.

And thanks to the Red Cross, local blood centers and other organizations that collect blood for human patients, we know that a supply of human blood products is usually readily available.

But where do life-saving blood products come from when an animal is in dire need?

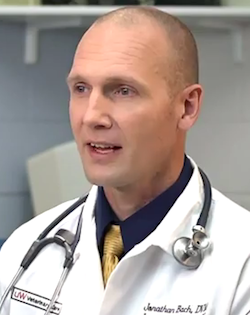

“It is a pretty constant need,” says Jonathan Bach, who directs emergency and critical care services for the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Veterinary Medicine’s Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital. “Like humans, animals can have problems with bleeding or trauma.”

Bach

A recent example, he says, was a dog that had consumed a rat poison that kills by inducing internal bleeding: “That dog needed some clotting factors, plasma,” explains Bach, who oversees a busy animal emergency room that often sees the most difficult or traumatic cases veterinarians are likely to encounter.

In a high-volume setting like UW–Madison’s Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, there are always a few units of dog and cat red blood cells on hand for emergencies, but that blood, just like human blood, has a limited shelf life and must be constantly replenished.

To do that, the hospital has its own Animal Blood Bank with a dedicated core of 12 dogs and 11 cats who serve as regular donors, many of them the animal companions of students or staff members at the UW–Madison School of Veterinary Medicine. “We actually have a waiting list of pets to become new donors,” notes Bach.

The typical canine blood donor is a healthy, larger dog — more than 50 pounds — that has been screened for blood borne parasites and diseases that affect the qualities of blood. Importantly, the dog donor possesses a good nature.

“We don’t sedate the dogs,” explains Bach, who says a typical blood draw from a dog takes about 7 to 10 minutes. “Cats are certainly different than dogs. Cats are a little more reclusive and sometimes have a little higher stress level in the hospital. They are sedated.”

Like people, dogs and cats have different blood types. Dogs are more complex, with at least eight different types. Cats have three.

“At times we can do a cross match to check for compatibility and we look at things like immune response,” says Bach. “Dogs in general are very tolerant of other dogs red blood cells. Cats are different and it is more important that they have a compatible crossmatch.”

The need for blood and plasma is not limited to cats and dogs. The horses and cows that cycle through the hospital’s large animal practice may also be in need of blood products. That’s where Maxine, Natalie and Drive Thru come in.

Maxine and Natalie, beautiful and pampered Holsteins, serve as the resident blood donors for the UW–Madison Veterinary Teaching Hospital’s bovine patients. “These (patient) cows are very valuable animals, sometimes worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, and when they need a transfusion, they really need it,” says Harry Momont, a professor of veterinary medicine who oversees the hospital’s large animal program.

While it is possible to purchase blood products for dogs and cats, and plasma for horses from commercial sources, that’s not possible with cows, explains Toni Schriver, the hospital’s large animal technical staff supervisor. And if a 1,500-pound cow needs a transfusion, she continues, you may need six to 12 liters of whole blood or plasma.

“A cow getting a blood transfusion is an extremely rare event,” says Momont, “It happens only about four or five times a year.”

More commonly, Maxine and Natalie donate the gastrointestinal microflora found in fluid obtained from their rumens. When cows go off their feed or have other gastrointestinal issues, the donated rumen fluid is used to help jump-start the ailing cow’s digestive tract.

Also, when it comes to donated cow or horse blood products, screening is required to ensure that the products are diseases free and can be safely used to treat an ailing or injured animal.

At present, the UW–Madison Veterinary Teaching Hospital does not have a donor horse.

Their most recent resident donor horse, Drive Thru, retired this fall after seven years of donating blood and serving as a calming presence and companion for any skittish equine patients at the hospital. In the hospital’s large animal practice, Drive Thru was a star, getting presents and mail from the children of clients and visitors and occasionally popping his head into the waiting room for peppermint candy, his favorite.

Finally, donor animals also play an important role in the School of Veterinary Medicine’s teaching mission. For students, the animals represent an opportunity to get hands-on experience handling animals, conducting exams and drawing blood.