New form of cell division found

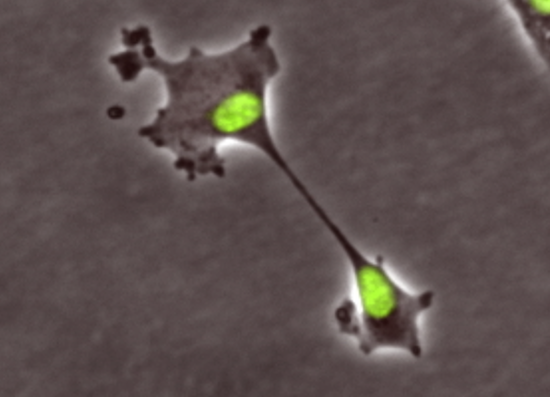

A new form of cell division, klerokinesis, causes a cell to divide into two daughter cells. Klerokinesis differs from the normal cell division, called cytokinesis. The discovery may lead to techniques to prevent some cancers from developing. View a short video of the process here.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center have discovered a new form of cell division in human cells.

They believe it serves as a natural back-up mechanism during faulty cell division, preventing some cells from going down a path that can lead to cancer.

“If we could promote this new form of cell division, which we call klerokinesis, we may be able to prevent some cancers from developing,” says lead researcher Dr. Mark Burkard, an assistant professor of hematology-oncology in the department of medicine at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health.

Burkard presented the finding on Monday, Dec. 17 at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology in San Francisco.

A physician-investigator who sees breast cancer patients, Burkard studies cancers in which cells contain too many chromosomes, a condition called polyploidy.

About 14 percent of breast cancers and 35 percent of pancreatic cancers have three or more sets of chromosomes, instead of the usual two sets. Many other cancers have cells containing defective chromosomes rather than too many or too few.

Burkard

“Our goal in the laboratory has been to find ways to develop new treatment strategies for breast cancers with too many chromosome sets,” he says.

The original goal of the current study was to make human cells that have extra chromosomes sets. But after following the accepted recipe, the researchers unexpectedly observed the new form of cell division.

Until now, Burkard and most cell biologists today accepted a century-old hypothesis developed by German biologist Theodor Boveri, who studied sea urchin eggs. Boveri surmised that faulty cell division led to cells with abnormal chromosome sets, and then to the unchecked cell growth that defines cancer. With accumulated evidence over the years, most scientists have come to accept the hypothesis.

Normal cell division is at the heart of an organism’s ability to grow from a single fertilized egg into a fully developed individual. More than a million-million rounds of division must take place for this to occur. In each division, one mother cell becomes two daughter cells. Even in a fully grown adult, many kinds of cells are routinely remade through cell division.

The fundamental process of cells copying themselves begins with a synthesis phase, when a duplicate copy is made of cell components, including the DNA-containing chromosomes in the nucleus. Then during mitosis, the two sets are physically separated in opposite directions, while still being contained in one cell. Finally, during cytokinesis, the one cell is cut into two daughter cells, right at the end of mitosis.

Burkard and his team were making cells with too many chromosomes-to mimic cancer. The scientists blocked cytokinesis with a chemical and waited to see what happened.

“We expected to recover a number of cells with abnormal sets of chromosomes,” Burkard explains.

The researchers found that, rather than appearing abnormal, daughter cells ended up looking normal most of the time. Contrary to Boveri’s hypothesis, abnormal cell division rarely had long-term negative effects in human cells.

So the group decided to see how the human cells recovered normal sets of chromosomes by watching with a microscope that had the ability to take video images.

“We started with two nuclei in one cell,” Burkard says. “To our great surprise, we saw the cell pop apart into two cells without going through mitosis.”

Each of the two new cells inherited an intact nucleus enveloping a complete set of chromosomes. The splitting occurred, unpredictably, during a delayed growth phase rather than at the end of mitosis.

The scientists did a number of additional experiments to carefully make sure that the division they observed was different than cytokinesis.

“We had a hard time convincing ourselves because this type of division does not appear in any textbook,” Burkard says.

Over time, they found that only 90 percent of daughter cells had recovered a normal complement of chromosomes. Burkard would like to leverage that statistic up to 99 percent.

“If we could push the cell toward this new type of division, we might be able to keep cells normal and lower the incidence of cancer,” he says.

Burkard now thinks that among all those rounds of cell division an organism goes through, every once in a while cytokinesis can fail. And that this new division is a back-up mechanism that allows cells to recover from the breakdown and grow normally.

The group has dubbed the new type of division klerokinesis to distinguish it from cytokinesis. Burkard enlisted the help of William Brockliss, UW assistant professor of classics, to come up with the name; klero is a Greek prefix meaning “allotted inheritance.”

Collaborators on the project include Beth Weaver, UW assistant professor of cell and regenerative biology; Dr. Alka Choudhary; Robert Lera; Melissa Martowicz and Jennifer Laffin.