UW prof’s award-winning ‘Slow Violence’ gives voice to global struggle

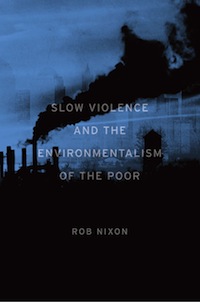

The cover of Rob Nixon‘s new book features black smoke, drifting across a dreary cityscape.

The title, “Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor,” hints at grim topics within: radiation contamination, toxic drift, the destruction of ecosystems and communities to make way for dams or mines.

But the book, which has just won the 2012 American Book Award, locates triumph and hope in the voices of those bearing witness to these dangers. By framing a discussion of “slow violence” — insidious, long-term threats to people and landscape — against a global body of literature, Nixon reveals the critical role of writer-activists in the fight for environmental justice around the world.

This month at the University of California, Berkeley, the Before Columbus Foundation awarded the honor to Nixon, a professor of English at UW–Madison. As part of its mission to promote contemporary American multicultural literature, the nonprofit foundation created the American Book Award to recognize outstanding achievement from across a wide spectrum of the literary community.

It’s a “writer’s award,” bestowed by other writers, and for this reason Nixon was especially pleased to receive it.

“It means a great deal, because it’s not an academic award, it’s typically for a more general audience,” Nixon says. “It came out of the blue — I didn’t know it had been submitted. But I was very pleased to be in that company.”

“Slow violence” is the term Nixon uses to define damage wrought over decades, as opposed to instant calamities created by more spectacular, headline-worthy events.

Nixon

“Stories of toxic buildup, massing greenhouse gases, and accelerated species loss due to ravaged habitats are … cataclysms in which casualties are postponed, often for generations,” Nixon writes. “How can we turn the long emergencies of slow violence into stories dramatic enough to rouse public sentiment and warrant political intervention? …”

Nixon, who joined the UW–Madison faculty in 1999 to teach environmental literature as well as public writing and nonfiction in the UW’s creative writing program, writes for The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Independent, the Village Voice and many other publications.

“Slow Violence” was completed “in a burst of intensive energy” while Nixon was a senior fellow at UW’s Institute for Research in the Humanities from 2009-12, but the catalyst for the book was a much earlier essay he’d written in 1996 for the London Review of Books: “Pipedreams,” about the arrest and execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nigerian activist.

Saro-Wiwa, a member of the Ogoni ethnic group, spoke forcefully against the devastation wrought by oil companies in the Niger Delta. Before he was executed (on what many claim were trumped-up charges of murder), Saro-Wiwa penned novels, plays, children’s tales, newspaper columns, several TV shows, and a memoir that drew attention to what he called “the deadly ecological war against the Ogoni.”

After delving deeply into Saro-Wiwa’s case, Nixon began to think about the growing body of literature in which writers were taking up issues of environmental justice.

“I realized I wanted to connect the work Saro-Wiwa had done to the work of other writer-activists, like Arundhati Roy and Jamaica Kincaid, to create a transnational book,” says Nixon.

The book covers a lot of territory: the Middle East, the Caribbean, as well as different parts of Africa, India and the United States. In sharing the work of those who grew up watching slow violence unfold in their homelands, Nixon wanted to dispel the notion that environmentalism emanates primarily from the wealthy West.

“There’s a very common misconception that environmentalism is a luxury issue, for people who don’t have more urgent questions of survival confronting them,” he says. “But these struggles have been going on for decades, eons.”

One major challenge confronting writer-activists from more troubled areas, says Nixon, is fear of reprisal. Most contend with authoritarian regimes that expect them to remain silent.

“Speaking out is doubly difficult, and doubly inspiring, when it comes from those quarters,” says Nixon.

In the book, Nixon links Wangari Maathai, who won the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize for the founding of Kenya’s Green Belt movement, with American environmental writer Rachel Carson. The two faced similar ridicule. Carson was labeled a “spinster communist” who was overly interested in genetics. Maathai was called “un-womanly” and “un-African.”

“You can see, in the two books — ‘Silent Spring’ and Mathai’s memoir, ‘Unbowed’ — the challenge that both writers faced in being scientifically dispassionate, while being emotionally gripping,” Nixon says.

A video interview with Nixon can be viewed here.

—Mary Ellen Gabriel