Global villain or strategic genius? Neither, asserts new book on Henry Kissinger

Author: “What are your core moral principles — the principles you would not violate?”

Henry Kissinger: “I am not prepared to share that yet.”

This peculiar exchange hints at one of the central themes of a new book about the enigmatic statesman, “Henry Kissinger and the American Century,” written by University of Wisconsin–Madison historian Jeremi Suri. In examining Kissinger’s complicated and controversial legacy, Suri creates a portrait of a man whose political career was motivated by deep moral convictions, yet the outcomes of many of his policies were viewed as morally horrendous.

“What I am interested in is how can someone who is so smart — and entered politics for moral reasons, because the experience of the Holocaust loomed so large in his life — how does someone like that produce results such as the bombing of Vietnam?”

Jeremi Suri, profesor of history

While many books have been written about Kissinger’s policies, Suri says his book is the first to offer a deeper understanding of the man based on Kissinger’s remarkable life history. Suri conducted intensive research on all phases, including Kissinger’s childhood in Furth, Germany; the disturbing rise of Hitler and his family’s status as Jewish-German refugees in New York City; his return to occupied Germany as an American soldier in World War II; his Harvard-educated rise to international prominence as a Cold War strategist; and his foreign policy counsel to nearly every president of the modern era.

Suri’s book examines how these life experiences — especially Kissinger’s Jewishness — impacted the way he viewed the world and its threats. Suri also had unprecedented access to the man himself, getting the opportunity over three years to have more than a dozen sit-down interviews with Kissinger.

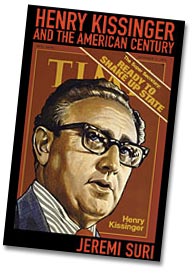

Henry Kissinger and the American Century, written by UW–Madison historian Jeremi Suri, is published by Harvard University Press.

Kissinger is an extremely polarizing figure, and much of what is written about him falls into the extreme camps of “strategic genius” or “war criminal.” “Kissinger and the American Century,” released in early June by Harvard University Press, argues that neither camp is correct.

“What I am more interested in,” Suri says, “is how can someone who is so smart — and entered politics for moral reasons, because the experience of the Holocaust loomed so large in his life — how does someone like that produce results such as the bombing of Vietnam?”

The key to that answer begins with Kissinger’s youth in Germany, Suri says, where he witnessed the sophisticated and highly democratic society of Weimar, Germany, destroyed by the Nazi regime with little apparent resistance. It deeply impressed in Kissinger a view that democracies were inherently weak and frequently under siege, and that protecting Western civilization sometimes requires the morally compromising need to support “the lesser of two evils.”

“The experience of being a Jew in World War II certainly made him more skeptical of human rights and idealism,” Suri says, noting that the phrase “human rights” is almost completely absent from his policy lexicon. “I think he saw — in his own phrase — that there was ‘evil in the world’ and that for greater moral purposes, you had to presume that sometimes you had to use immoral means.”

Kissinger’s legacy as secretary of state from 1969-1977 will be tarnished by his policy of escalated bombings in Vietnam that killed thousands of innocent civilians, as well as his open support for General Pinochet’s murderous regime in Chile. Suri says that Kissinger had a propensity to too quickly dismiss legitimate concerns about the human rights implications of his decisions.

While Kissinger made costly mistakes in his career, he is without question the chief architect of post-World War II American foreign policy — an architecture that is still standing today, Suri notes. The opening of U.S. relations with China, a hallmark Kissinger achievement, would have been impossible without his unwavering commitment to diplomacy with friends and adversaries.

On the topic of Kissinger’s Jewish heritage, Suri uncovered evidence that it had a ubiquitous impact on his political life — a fact, Suri says, Kissinger stubbornly refuses to acknowledge. “He spent his entire life surrounded by people who were either anti-Semitic or at least mildly prejudiced against Jews,” he says, including President Nixon. “He had to appeal to these people for power.”

Suri looks through Vietnam-era political posters in the manuscript reading room of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Photo: Michael Forster Rothbart

The issue was especially acute during his work for a peace agreement in the Middle East in the early 1970s. Suri says that every time he met with leaders from Saudi Arabia, he was handed a copy of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a fictitious anti-Semitic pamphlet that describes a conspiracy theory about Jewish plans for world domination.

“Every time he meets with Egyptians, there was an assumption that he speaks on behalf of the Jewish world,” Suri says. “Every time he meets with Israelis, there’s a presumption he should be doing more because he’s ‘one of them.’ His Jewishness is always on the table.”

But remarkably, rather than disable his political career, he found ways to use the prejudices to his political advantage by essentially playing it differently in negotiations with Israelis and Arab nations, Suri says. And in spite of those prejudices, he is highly respected by leaders throughout the world.

There are other Kissinger traits that help explain his profound political influence and longevity. He has a relentless work style and “simply outworked everyone around him,” and has an amazing capacity to assimilate massive amounts of information and frame issues in forceful ways. For example, he carefully scrutinized briefing papers in more depth than anyone else and preferred to review original documents to extract the information he needed.

“That gave him enormous power because he was often the only person in the room who knew the whole story,” he says. “He’s the type of thinker who can lay out three options and make it clear in the end there’s only one good option — his.”

Suri takes Kissinger’s legacy all the way up to the present-day war in Iraq, which perhaps represents the first significant diversion from the Kissinger template of embracing moderate regimes (usually dictatorships), maintaining access to (but not control over) oil resources, and using indirect force through proxy regimes to maintain stability.

“What the Bush administration did differently is they tried to promote democracy, but Kissinger was always opposed to the idea that you can bring democracy to the Middle East,” Suri says. “Ironically, the failure of the Bush administration to bring democracy to Iraq is going to result in a more Kissingerian world. We will be essentially creating a proxy regime, the same thing Kissinger was doing in Egypt and Israel.”

Kissinger’s political ideals centered on protecting the greatness of Western civilization, Suri says. “What does he mean by Western civilization? Not necessarily democracy, but law and order, rules of fairness, basic personal freedoms and a hierarchy of values.”

Suri says that Kissinger — who had witnessed the absolute worst of hatred and violence during the Nazi regime — believes that hatred and violence are persistent forces in the world and that foreign policy must reflect that reality. Defeating those forces usually requires a combination of diplomacy, force and compromise — rather than rhetoric about democracy and moral absolutes.

Suri concludes that despite the intense criticism of Kissinger’s legacy, critics have failed to offer a more effective foreign policy alternative. “The 21st Century awaits Kissinger’s successor,” he writes.