Fernie Rodriguez brings an empathetic lens to identity and inclusion role in Student Affairs

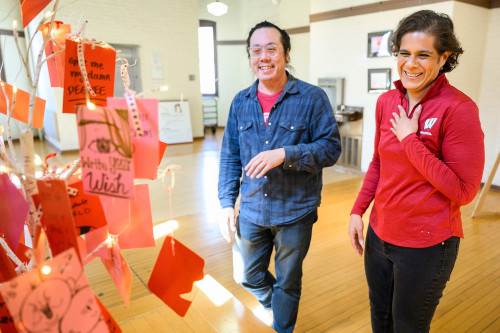

At left, Fernie Rodriguez, associate vice chancellor for Student Affairs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, speaks with Kevin Wong, program coordinator of the Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Student Center, at the Red Gym’s 1973 Gallery. Photo: Althea Dotzour

As a PhD student at the University of Minnesota, Fernie Rodriguez seemed to be everywhere — teaching undergraduate courses, working in the offices of administrative units, leading fitness classes at the university’s wellness center.

From the outside, it looked like Rodriguez was a highly motivated multi-tasker. That wasn’t wrong, just not the whole story.

“I really was a successful graduate student,” says Rodriguez, who uses they/them pronouns. “But the truth of it was, I was still navigating poverty. I worked anywhere on campus that would have me.”

For Rodriguez, working multiple jobs wasn’t unusual. It had been the norm for Rodriguez as an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin and as a master’s degree student at New York University. Rodriguez refers to it as “a constant effort to escape a legacy of poverty.”

“As an undergraduate, I started understanding that I didn’t have the money to go on an awesome spring break trip like so many of my peers,” Rodriguez says. “I couldn’t afford things at the university bookstore or at the union. There were many moments when I didn’t know where my next meal was coming from.”

Those experiences and many others now inform the work Rodriguez does at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. As an associate vice chancellor, Rodriguez, who began in January, leads the Student Affairs identity and inclusion portfolio. This comprehensive array of programs and services is designed to support student success, with special interest in underrepresented student populations.

Rodriguez’s portfolio includes the Multicultural Student Center, the Gender and Sexuality Campus Center, the McBurney Disability Resource Center, the Office of Inclusion Education, and University Veteran Services. Rodriguez also will guide the newly renamed and relocated Center for Interfaith Dialogue, which helps students explore faith identities, as well as campus collaborations aimed at improving support for first-generation students.

Rodriguez and Wong admire an illuminated tree with ornaments at the APIDA Art Gallery. Photo: Althea Dotzour

Rodriguez, who grew up in El Paso, Texas, was a first-generation college student. It remains a core identity.

“Regardless of what I accomplish, I will always think of myself as a first-generation person — a first-generation student, a first-generation instructor, a first-generation administrator,” Rodriguez says. “I will always carry with me that legacy — the joys, the responsibilities and the burdens.”

Rodriguez’s father immigrated from Mexico and worked as a boot finisher in a Tony Lama factory. Rodriguez’s Mexican American mother cashiered at Walgreens.

Rodriguez was an “A” student and senior class president in high school. At the time, Texas had just passed a rule granting students in the top 10% of their high school graduating classes automatic admittance to a state college. Rodriguez easily cleared that bar but knew little about higher education.

“I was admitted to the University of Texas at Austin not even knowing that it was the flagship campus,” Rodriguez says. “That was the level of my naivete.”

Rodriguez says their motivation for going to college had little to do with the transformative power of higher education. They were beginning to grapple with the ramifications of a queer identity and knew that some family members would not react well.

“The beginning of my pursuit of higher education was not because I wanted a degree,” Rodriguez says. “It was because I wanted to get the heck out of the house.”

College initially was “messy,” Rodriguez says.

“I came from a low-income household in a predominately Mexican community and went to a very wealthy institution where I was suddenly in the minority. My language was not spoken widely. My culture and my food were considered ‘the other.’”

Rodriguez struggled, turning to unhealthy coping mechanisms, including alcohol.

“Looking back, I have a lot of empathy for that person,” Rodriguez says. “And then I think, ‘God, I was bold.’ I lived in this fractured world. On one hand, I was a resident assistant, an orientation advisor, a student leader. On the other hand, I was deeply coping with everything thrown at me, including poverty.”

Rodriguez’s grades initially suffered but rose as the years went on. As a resident assistant at UT–Austin, Rodriguez first heard someone mention the words “student affairs.” A career goal was born.

“I just knew that’s what I wanted to do, and I knew I would need a graduate degree to do it.”

Rodriguez earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology from UT–Austin in 2005, then a master’s degree in higher education student personnel administration from NYU in 2009. Years of work in higher education in Minnesota followed. At Carleton College in Northfield, Rodriguez served as a hall director and as a liaison to a group working to increase college access for underrepresented, undocumented, and low-income middle and high school students of Mexican/Latino backgrounds. At Macalester College in St. Paul, Rodriguez was a residence hall director and interim assistant dean of students.

In 2018, Rodriguez completed a PhD in higher education from the University of Minnesota. Their dissertation examined the internalized masculinity constructs of six first-generation Mexican American gay undergraduate men. Rodriguez wanted to understand the ways that internalized masculinity expectations shaped the college experiences of these students.

The dissertation topic hit close to home. Not long after completing the PhD, Rodriguez had the time and the space to dig deeper into their own issues around culture and masculinity.

“In 2020, I had to deal with myself,” Rodriguez says. “I had been very good at distracting myself with the academic grind — the back-to-back meetings, the manuscripts, the conference travel. When all that was gone, I had to confront this feminine fire that was always there but that I had worked so hard to diminish — extinguish, really. I had to start understanding that maybe I wasn’t a gay man. Now I can confidently say I am transgender.”

Rodriguez considers it evidence of the continual journey of self-discovery that everyone has access to. For so many years, Rodriguez says they felt confined to certain “boxes” that society had put them in. Many college students, especially those from underrepresented groups, struggle with this, too, Rodriguez says.

“Like all our students, I am healing but also evolving in my understanding of myself and the world,” Rodriguez says. “That, I believe, is the reason you pursue a college education. I want students — all students — to know that I am here for them on that journey.”

Tags: student affairs