Prohibition may have extended life for those born in dry counties

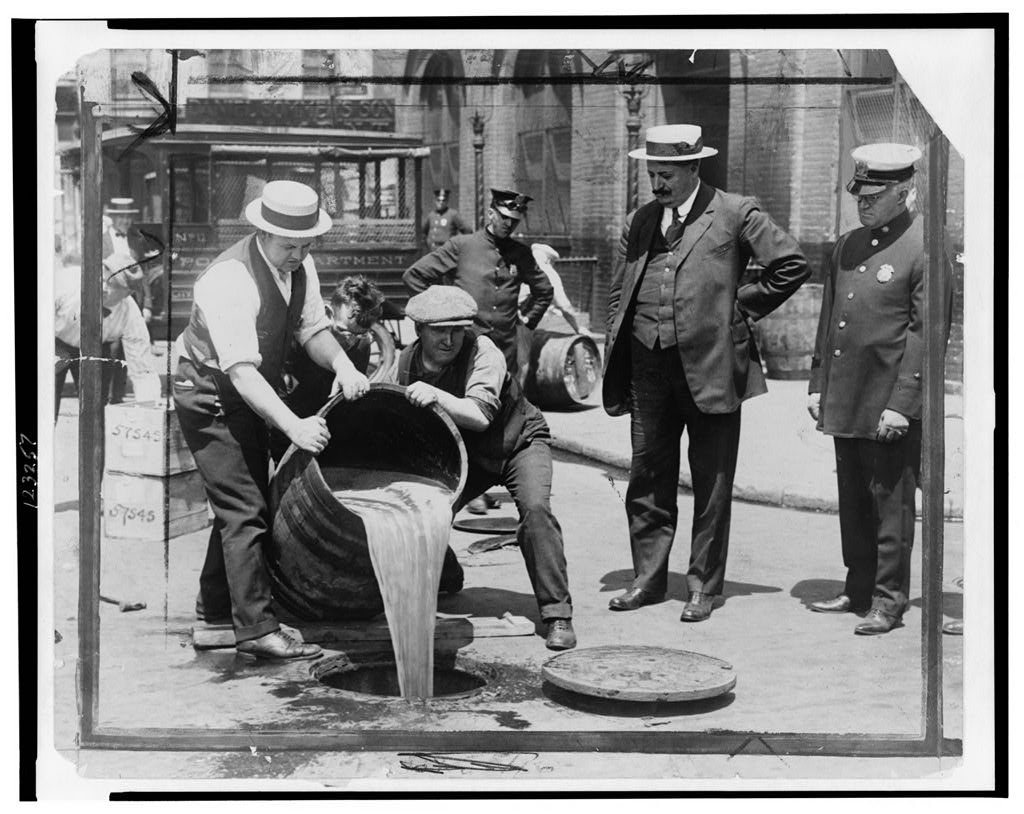

New York City Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach, right, watching agents pour liquor into sewer following a raid during the height of Prohibition. New research suggests that in counties where prohibition was in effect, residents saw an average increase in lifespan of 1.7 years. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Although widely considered a blunder of public policy, the alcohol prohibition laws of early 20th century America may have led to increased longevity for those born in places where alcohol was banned, according to new research from the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The study — recently published in the journal Economics and Human Biology and co-authored by Jason Fletcher of UW’s La Follette School of Public Affairs — is the first to research the long-term effects of Prohibition Era on longevity, adding to the understanding of the longer-term costs of alcohol exposure during pregnancy. The findings come as we mark the 90th anniversary of the repeal of Prohibition on Dec. 5, 2023. They also come at a time when the rate of women who drink during pregnancy has recently increased from 9.2 percent in 2011 to 11.3 percent in 2018, according to the study. A 2022 CDC report found that number now stands at nearly 14 percent.

Using advanced analytical methods on data from the Prohibition Era, this study provides important nuance to the assessment of Prohibition’s effects on public health and could have important implications for policies aimed at reducing maternal alcohol use.

Jason Fletcher

“Researchers now understand that exposures during pregnancy, due to interruptions to fetal development, can have long term cascading effects on later-life health,” Fletcher says. “Modern evaluation tools and new data opportunities allow us to look back at policies from 100 years ago to assess their long-term impact in ways we’ve never been able to do before.”

Fletcher and his co-author, Hamid Noghanibehambari from Austin Peay State University and an affiliate of UW–Madison’s Center for Demography of Health and Aging, used Social Security Administration death records from 1975-2005 that were linked to the 1940 U.S. census. They identified counties of residence and determined whether alcohol sales were legal or prohibited at the time of birth.

Because parts of the country became “dry” through state and federal regulation at different times between 1900-1930, data from this period served as a natural experiment for investigating these effects. Fletcher and Noghanibehambari were able to compare the old-age longevity of individuals who were exposed to prohibition laws during early life and childhood to those who were not.

They found that being born in a county that went dry due to state or federal regulations correlated with roughly 0.17 additional years of longevity during old age. Taking other factors into account, such as the likelihood of women drinking during pregnancy at a time when little was known about the dangers of maternal alcohol consumption, they calculated that Prohibition may have resulted in an average of 1.7 additional years for those born in counties where alcohol was banned.

To better understand the size of this observed increase in longevity, the study also compared these results with the overall change in life expectancy for Americans born between 1900-1930. Overall, this group experienced a sharp and unprecedented increase of about 11.8 years in life expectancy due to factors such as improvements in medical technology and increases in income and welfare. The effect of 1.7 years due to exposure to the temperance movement is equivalent to nearly 15% of the overall life expectancy improvements of those born at this time.

Along with recent studies that suggest that lowering alcohol availability due to Prohibition reduced mortality, decreased drug-related crime and improved child health, this research helps shed light on the effects of alcohol policy on public health.

This research is funded in part by the National Institute of Aging (R01AG060109) and the UW–Madison Center for Demography of Health and Aging through a National Institute of Aging core grant (P30 AG17266).