Sharing discoveries and imagining the future at the second annual Sustainability Symposium

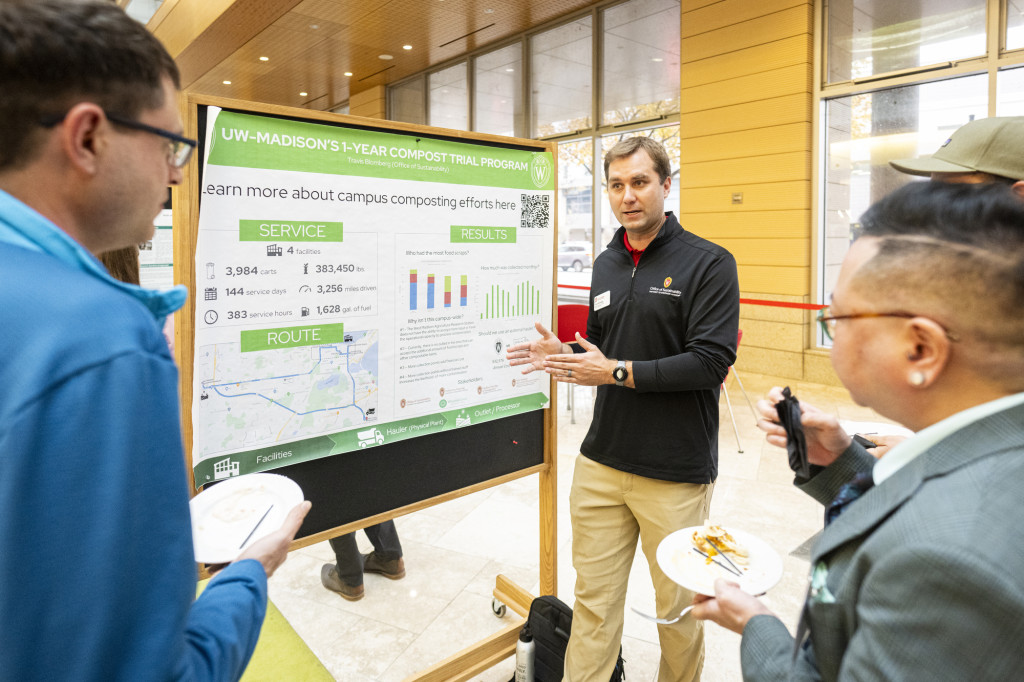

Over the course of the second annual Sustainability Symposium, nearly 400 students, faculty and staff gathered at the Discovery Building to engage in exciting conversations about research, education and the advancement of sustainability at UW–Madison.

From a keynote address on improving food security through a circular economy, to lightning talks on campus sustainability initiatives and poster sessions on research projects across UW–Madison, enthusiastic attendees learned, swapped ideas and inspired one another.

The keynote address was given by Weslynne Ashton, a professor of environmental management and sustainability at Illinois Institute of Technology. She focused on a theme that carried throughout the symposium: real world applications of research.

Keynote speaker Weslynne Ashton, a professor of environmental management and sustainability at Illinois Institute of Technology, spoke about a community project to create “love fridges,” which she described as a form of mutual aid, where neighbors help neighbors in times of need. Photo by Lauren Graves/UW–Madison

“What if our food system was organized around principles of love, justice and circularity, rather than money, exploitation and consumption?” she asked.

Ashton, who works on increasing sustainability and equity in urban food systems, spoke about a community project to create “love fridges,” which she described as a form of mutual aid, where neighbors help neighbors in times of need.

“People are invited to take what they need and leave what they can,” she said. “They are an expression of solidarity, not charity.”

Ashton described how she collaborates to develop food waste prevention and management strategies for the City of Chicago. In the city, the predominantly white and affluent north side of Chicago produces more waste and enjoys more access to food than the predominantly Black and brown south and west sides.

To confront the city’s mounting inequities, Ashton gathered food providers, food rescue organizations, food waste recyclers and policymakers to devise a more cohesive strategy.

This example helped introduce her argument for a circular economy. A linear economy, she said, carries the belief that the Earth holds unlimited resources, with enough space to accommodate the millions of tons of food Americans waste each year. But in reality, Ashton said, that pushes against the limits of our planet’s biogeochemical functions.

A circular economy on the other hand, is restorative and regenerative by design. She said the new economic model can respect the planet’s boundaries through recycling and waste reduction.

“Our food system and food waste is a complex challenge that’s affecting both people and planet,” she said. “We have to confront the values that are inherent in our linear economy and find creative ways to navigate the tensions that are required for our food systems transformation to make space for justice, for equity and for circularity.”

Matt Ginder-Vogel, an environmental chemistry and technology professor at UW, spoke during the lightning talks round about a new initiative for sustainability research. Photo by Lauren Graves/UW–Madison

During the symposium’s lighting talks, Matt Ginder-Vogel announced the start of the Sustainability Research Hub, a Nelson Institute and Office of Sustainability initiative “to make the University of Wisconsin–Madison a preeminent destination for sustainability research.” The hub will facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration toward sustainability, bringing researchers together to apply for large, interdisciplinary grants and coordinating the proofreading, editing and graphic design of their projects.

“We want to add to the body of research that is already happening at the university and bring people into sustainability research that don’t have the chance to participate now,” said Ginder-Vogel, who will oversee the program.

Other presentations detailed ongoing sustainability projects on campus like tracking the volume and cost of food waste in dining and culinary services, the financial and environmental benefits of opting to use water-based cleaning systems on campus and the solutions resulting from efforts to connect local government partners with UW–Madison student researchers.

Like last year, the Sustainability Symposium welcomed a major UW–Madison decisionmaker who voiced support for sustainability initiatives and research. Provost Charles Lee Isbell Jr. described the symposium attendees’ work as both essential and the living embodiment of the Wisconsin Idea. He added that the university needs to embrace this work and continue to strive to be a leader in sustainability.

“What is the world we’re going to create if we act and behave in the right ways, and what is the world if we do nothing 25 years from now?” he asked.

Provost Charles Lee Isbell Jr. described the symposium attendees’ work as both essential and the living embodiment of the Wisconsin Idea. Photo by Lauren Graves/UW–Madison

The future is on Isbell’s mind — and the minds of the hundreds of symposium attendees who feel compelled to work thoughtfully, urgently and collaboratively to prevent the worst results of climate change.

“I care about immortality,” Isbell concluded. “When I was young, I wanted to live forever.”

To Isbell, immortality means, “that you somehow touched not just this generation but the generation that follows and the generation that follows that. You do work and have change and make impact. That’s the closest most of us will ever come to immortality, and it’s the kind of immortality that’s worth having.”

Tags: sustainability