Cell therapy is the future, and Wisconsin is the place, UW–Madison expert tells Technology Council

Medicine is rapidly approaching a great advance that will augment or replace drugs with human cells for treating a range of intractable conditions, an expert in cell therapy told the Wisconsin Technology Council on June 26.

Jacques Galipeau, director of advanced cell therapy at the School of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Program for Advanced Cell Therapy, University of Wisconsin–Madison

Jacques Galipeau, assistant dean for therapeutics discovery at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, described the potential of building on the innate capacities of human cells that are manipulated to target particular diseases.

The strategy uses what he calls a “living cell pharmaceutical.”

Less than two years after Galipeau was hired to start the Program for Advanced Cell Therapy at the School of Medicine, PACT has obtained an FDA Investigational New Drug (IND) permit to test a treatment for complications of bone marrow transplant.

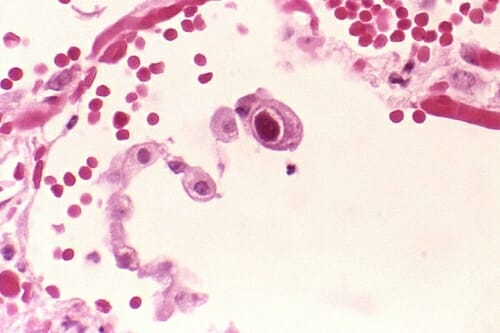

Usually, the immune system controls many latent virus infections, but those viruses can run rampant after radiation treatment kills the bone marrow before transplant.

The central cell shows the dramatically enlarged nuclei characteristic of cytomegalovirus in the lung. CDC/Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

A cell transplant treatment in Germany controls cytomegalovirus in 80 percent of patients. “Germany considers this a clinical service like a blood transfusion; it’s the best practice, but you can’t do that here,” says Galipeau. “Startups that apply for an IND for these cases can wait years and cost $5 to $10 million. We got our first IND in nine months.”

Drug treatment for cytomegalovirus can cost upwards of $60,000, and it doesn’t always work. “Our goal is to improve survival, reduce hospital stays and reduce cost,” says Galipeau. “We think this approach could cost $11,000 to $15,000 and also be more effective.”

Many emerging cell therapies target cancer. Perhaps the most convincing evidence of the power of engineered immune cells to defeat cancer arose in 2012 in Pennsylvania. In one case, white blood cells from a girl dying of leukemia received genes that directed an attack on cancer cells. “She is cured,” Galipeau said.

The only genetically engineered immune cell on the U.S. market was approved last year for treating lymphoma. But the cost — $475,000 per treatment for the cells alone — is “the single biggest headwind,” Galipeau said.

And that price only buys the “parts,” he adds. Because the treatment puts the immune system in overdrive, labor – including doctor and hospital costs – could add another $300,000 or more to the price.

“Our job is to push the envelope and develop better/cheaper ways of deploying advanced cell treatments to allow access for all who are in need.”

Jacques Galipeau

With costs pushing toward $1 million per treatment, “there’s an urgent need to develop disruptive ‘living cell pharmaceutical’ technologies which will improve outcomes and allow for sustainability for the health care market,” Galipeau says. “Our job is to push the envelope and develop better/cheaper ways of deploying this technology to allow access for all who are in need.”

Galipeau, who joined the school of medicine in 2016, chose UW–Madison because “the ecosystem was very conducive for development of the technology that I am passionate about. All the pieces are here, and things are changing rapidly.”

A key component was the experimental attitude and history of UW–Madison. In 1966, when bone marrow transplants required cells from an identical twin, UW scientist Fritz Bach invented a test to identify suitable donors from a much broader range of possibilities. “In 1968, the first two bone marrow transplants from non-blood related donors were matched by Bach’s work,” Galipeau said, “so we really are the folks who enabled bone marrow transplant as a life saving technology.”

About 9,000 allogeneic transplants, using donated cells, are performed nationwide each year, largely to correct blood cancers. (A larger number of bone marrow transplants involve re-infusion of the patient’s own blood stem cells.)

Blood-forming stem cells ready for transfusion into a patient after bone marrow has been eliminated by radiation. Wikipedia

The university, Galipeau said, “has also invested in a pipeline of discovery in cell technologies, from Jamie Thomson’s discovery of embryonic stem cells, to a center focused on stem cells and regenerative medicine and a department of regenerative biology. Not all universities have invested in that space.”

PACT has completed a cell manufacturing lab that complies with the exacting “good manufacturing practices” standards needed for clinical trials. “We have built in the most expensive real estate in Wisconsin — inside UW hospital — and received certification two weeks ago,” said Galipeau. The key personnel are already on board, he adds: medical director Inga Hofmann and Rupa Pike, director of cell manufacturing.

UW–Madison also has doctors willing to guide the studies that will make or break cell therapy companies. “If you are a clinician, you need a pioneer spirit to do something that has never been done before,” Galipeau says, “and there are already many like that here.”

Madison also benefits from a panoply of life science companies, Galipeau adds. “I take my pilgrim stick and go to meet these companies, and ask, ‘What is your gap analysis to help us meet the Wisconsin idea? If you are not doing anything with the university, what would make it attractive?’ For transformative growth we need better partnerships.”

As a point of contact for companies interested in cell technology, “I can play matchmaker,” Galipeau says. “If a company’s technology might be applicable to a heart problem, I can connect them with a cardiologist who has the bandwidth to run a trial.”

Although cell-based treatments have many possible applications, “We are not going to partner with anybody for anything. We are interested in addressing catastrophic illnesses, where people are dying or there is substantial morbidity. Let the easy stuff be done by somebody else.”

Galipeau traces his enthusiasm for the project from his face-to-face work with patients. “I’m a hematologist-oncologist, and I see patients every week. Not a week goes by when I don’t want new tools. We are always looking for tools that will impact the outcome, prevent death, and allow the patient to walk out of hospital. That’s what I am talking about.”